Fin Garden in Kashan preserves centuries of history

Persian garden is far more than a collection of trees and water; it stands as one of the most enduring and profound expressions of Iranian art, architecture, and philosophy throughout history.

Morteza Ahmadi Nejat, a journalist, wrote in a note published by chtn.ir that Persian gardens, deeply rooted in ancient rituals and religious beliefs, have always symbolized a “promised paradise” (Pardis) on the Earth. From both mythological and religious perspectives, the Iranian garden reflects cosmic order, where water — the source of life — shade — a refuge from the scorching desert sun — and geometric symmetry — a symbol of divine perfection — are intricately intertwined.

The concept of the Persian garden is based on a structured fourfold layout, often centered around a pool where the four elements converge. The history of Iranian gardens stretches back to the Achaemenid era, but they reached their peak during the Sassanid period, particularly after the advent of Islam and the development of the Chaharbagh (fourfold) design in the Safavid era. Among these, the Fin Garden of Kashan, Isfahan Province, stands out as one of the most complete and well-preserved examples, holding a special place in Iran’s cultural heritage.

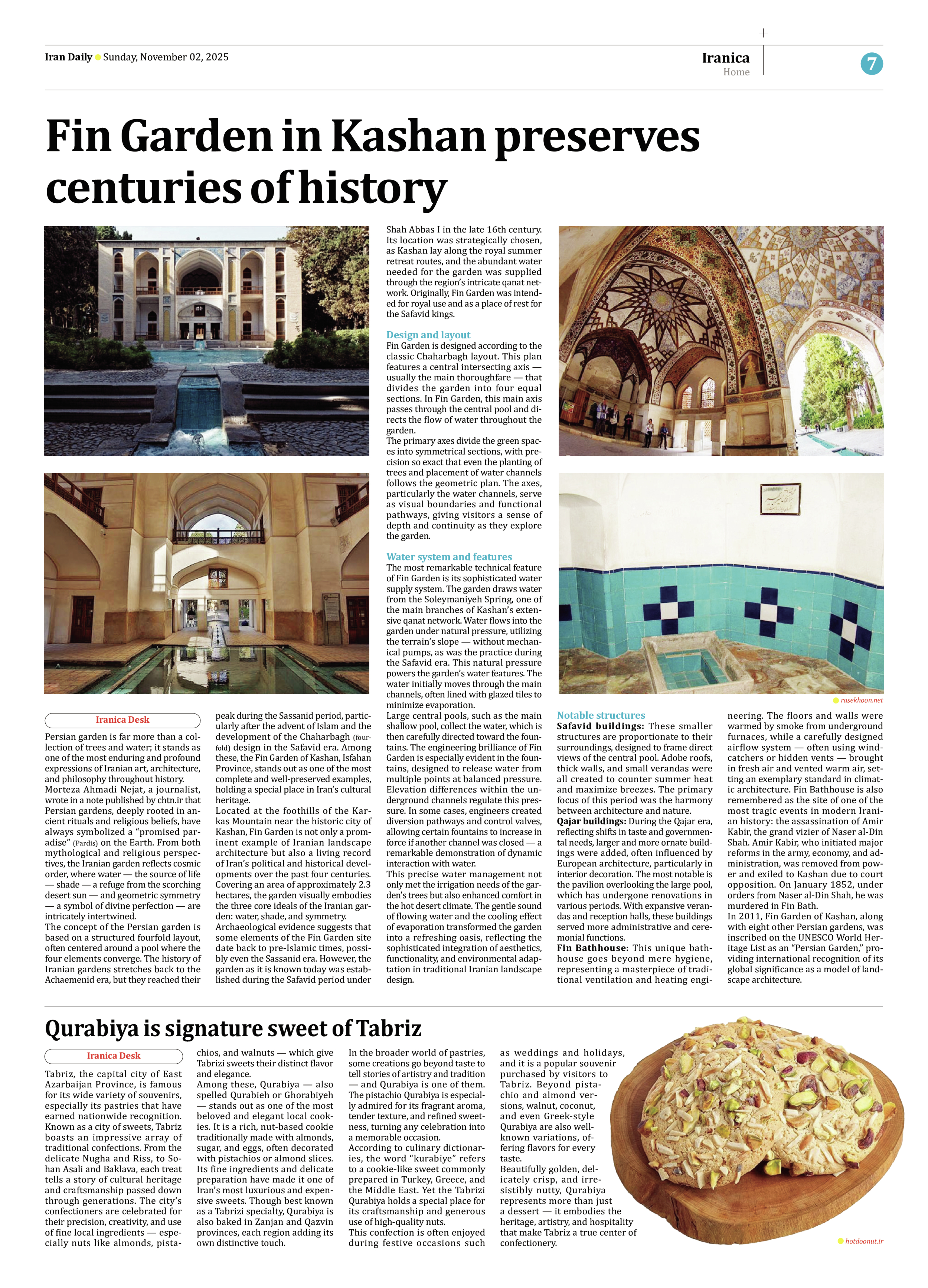

Located at the foothills of the Karkas Mountain near the historic city of Kashan, Fin Garden is not only a prominent example of Iranian landscape architecture but also a living record of Iran’s political and historical developments over the past four centuries. Covering an area of approximately 2.3 hectares, the garden visually embodies the three core ideals of the Iranian garden: water, shade, and symmetry.

Archaeological evidence suggests that some elements of the Fin Garden site date back to pre-Islamic times, possibly even the Sassanid era. However, the garden as it is known today was established during the Safavid period under Shah Abbas I in the late 16th century. Its location was strategically chosen, as Kashan lay along the royal summer retreat routes, and the abundant water needed for the garden was supplied through the region’s intricate qanat network. Originally, Fin Garden was intended for royal use and as a place of rest for the Safavid kings.

Design and layout

Fin Garden is designed according to the classic Chaharbagh layout. This plan features a central intersecting axis — usually the main thoroughfare — that divides the garden into four equal sections. In Fin Garden, this main axis passes through the central pool and directs the flow of water throughout the garden.

The primary axes divide the green spaces into symmetrical sections, with precision so exact that even the planting of trees and placement of water channels follows the geometric plan. The axes, particularly the water channels, serve as visual boundaries and functional pathways, giving visitors a sense of depth and continuity as they explore the garden.

Water system and features

The most remarkable technical feature of Fin Garden is its sophisticated water supply system. The garden draws water from the Soleymaniyeh Spring, one of the main branches of Kashan’s extensive qanat network. Water flows into the garden under natural pressure, utilizing the terrain’s slope — without mechanical pumps, as was the practice during the Safavid era. This natural pressure powers the garden’s water features. The water initially moves through the main channels, often lined with glazed tiles to minimize evaporation.

Large central pools, such as the main shallow pool, collect the water, which is then carefully directed toward the fountains. The engineering brilliance of Fin Garden is especially evident in the fountains, designed to release water from multiple points at balanced pressure. Elevation differences within the underground channels regulate this pressure. In some cases, engineers created diversion pathways and control valves, allowing certain fountains to increase in force if another channel was closed — a remarkable demonstration of dynamic interaction with water.

This precise water management not only met the irrigation needs of the garden’s trees but also enhanced comfort in the hot desert climate. The gentle sound of flowing water and the cooling effect of evaporation transformed the garden into a refreshing oasis, reflecting the sophisticated integration of aesthetics, functionality, and environmental adaptation in traditional Iranian landscape design.

Notable structures

Safavid buildings: These smaller structures are proportionate to their surroundings, designed to frame direct views of the central pool. Adobe roofs, thick walls, and small verandas were all created to counter summer heat and maximize breezes. The primary focus of this period was the harmony between architecture and nature.

Qajar buildings: During the Qajar era, reflecting shifts in taste and governmental needs, larger and more ornate buildings were added, often influenced by European architecture, particularly in interior decoration. The most notable is the pavilion overlooking the large pool, which has undergone renovations in various periods. With expansive verandas and reception halls, these buildings served more administrative and ceremonial functions.

Fin Bathhouse: This unique bathhouse goes beyond mere hygiene, representing a masterpiece of traditional ventilation and heating engineering. The floors and walls were warmed by smoke from underground furnaces, while a carefully designed airflow system — often using windcatchers or hidden vents — brought in fresh air and vented warm air, setting an exemplary standard in climatic architecture. Fin Bathhouse is also remembered as the site of one of the most tragic events in modern Iranian history: the assassination of Amir Kabir, the grand vizier of Naser al-Din Shah. Amir Kabir, who initiated major reforms in the army, economy, and administration, was removed from power and exiled to Kashan due to court opposition. On January 1852, under orders from Naser al-Din Shah, he was murdered in Fin Bath.

In 2011, Fin Garden of Kashan, along with eight other Persian gardens, was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as an “Persian Garden,” providing international recognition of its global significance as a model of landscape architecture.