Story of tradition, struggle, revival in Alamdar-e Olya village of Hamedan

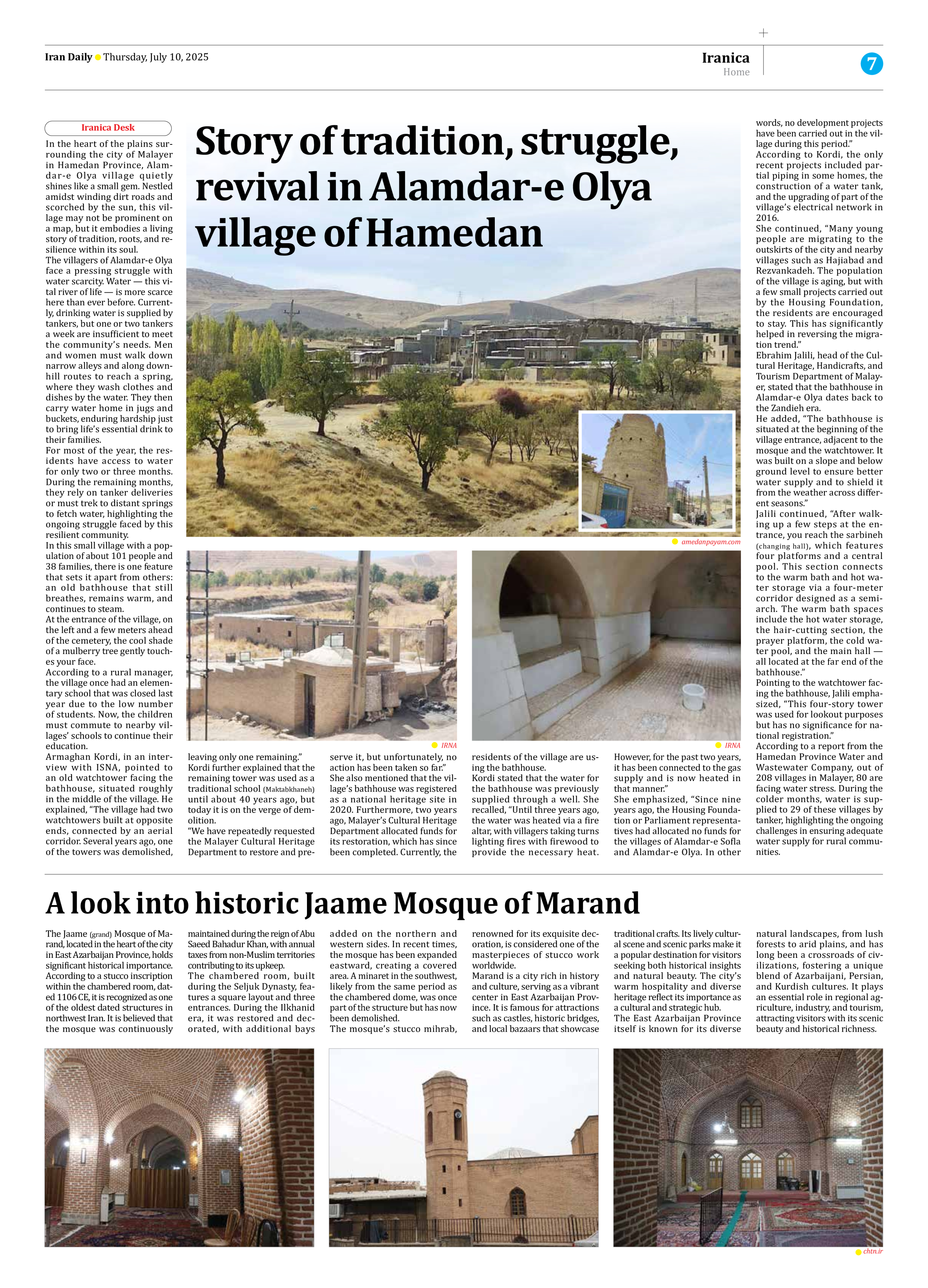

In the heart of the plains surrounding the city of Malayer in Hamedan Province, Alamdar-e Olya village quietly shines like a small gem. Nestled amidst winding dirt roads and scorched by the sun, this village may not be prominent on a map, but it embodies a living story of tradition, roots, and resilience within its soul.

The villagers of Alamdar-e Olya face a pressing struggle with water scarcity. Water — this vital river of life — is more scarce here than ever before. Currently, drinking water is supplied by tankers, but one or two tankers a week are insufficient to meet the community’s needs. Men and women must walk down narrow alleys and along downhill routes to reach a spring, where they wash clothes and dishes by the water. They then carry water home in jugs and buckets, enduring hardship just to bring life’s essential drink to their families.

For most of the year, the residents have access to water for only two or three months. During the remaining months, they rely on tanker deliveries or must trek to distant springs to fetch water, highlighting the ongoing struggle faced by this resilient community.

In this small village with a population of about 101 people and 38 families, there is one feature that sets it apart from others: an old bathhouse that still breathes, remains warm, and continues to steam.

At the entrance of the village, on the left and a few meters ahead of the cemetery, the cool shade of a mulberry tree gently touches your face.

According to a rural manager, the village once had an elementary school that was closed last year due to the low number of students. Now, the children must commute to nearby villages’ schools to continue their education.

Armaghan Kordi, in an interview with ISNA, pointed to an old watchtower facing the bathhouse, situated roughly in the middle of the village. He explained, “The village had two watchtowers built at opposite ends, connected by an aerial corridor. Several years ago, one of the towers was demolished, leaving only one remaining.”

Kordi further explained that the remaining tower was used as a traditional school (Maktabkhaneh) until about 40 years ago, but today it is on the verge of demolition.

“We have repeatedly requested the Malayer Cultural Heritage Department to restore and preserve it, but unfortunately, no action has been taken so far.”

She also mentioned that the village’s bathhouse was registered as a national heritage site in 2020. Furthermore, two years ago, Malayer’s Cultural Heritage Department allocated funds for its restoration, which has since been completed. Currently, the residents of the village are using the bathhouse.

Kordi stated that the water for the bathhouse was previously supplied through a well. She recalled, “Until three years ago, the water was heated via a fire altar, with villagers taking turns lighting fires with firewood to provide the necessary heat. However, for the past two years, it has been connected to the gas supply and is now heated in that manner.”

She emphasized, “Since nine years ago, the Housing Foundation or Parliament representatives had allocated no funds for the villages of Alamdar-e Sofla and Alamdar-e Olya. In other words, no development projects have been carried out in the village during this period.”

According to Kordi, the only recent projects included partial piping in some homes, the construction of a water tank, and the upgrading of part of the village’s electrical network in 2016.

She continued, “Many young people are migrating to the outskirts of the city and nearby villages such as Hajiabad and Rezvankadeh. The population of the village is aging, but with a few small projects carried out by the Housing Foundation, the residents are encouraged to stay. This has significantly helped in reversing the migration trend.”

Ebrahim Jalili, head of the Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts, and Tourism Department of Malayer, stated that the bathhouse in Alamdar-e Olya dates back to the Zandieh era.

He added, “The bathhouse is situated at the beginning of the village entrance, adjacent to the mosque and the watchtower. It was built on a slope and below ground level to ensure better water supply and to shield it from the weather across different seasons.”

Jalili continued, “After walking up a few steps at the entrance, you reach the sarbineh (changing hall), which features four platforms and a central pool. This section connects to the warm bath and hot water storage via a four-meter corridor designed as a semi-arch. The warm bath spaces include the hot water storage, the hair-cutting section, the prayer platform, the cold water pool, and the main hall — all located at the far end of the bathhouse.”

Pointing to the watchtower facing the bathhouse, Jalili emphasized, “This four-story tower was used for lookout purposes but has no significance for national registration.”

According to a report from the Hamedan Province Water and Wastewater Company, out of 208 villages in Malayer, 80 are facing water stress. During the colder months, water is supplied to 29 of these villages by tanker, highlighting the ongoing challenges in ensuring adequate water supply for rural communities.