Evolution of Persian and Arabic inscriptions

The rivalry between the Persian and Arabic languages in inscriptions on objects was already noticeable during the 10th to early 12th centuries, but it developed differently on the various materials.

On bronze (brass) this process proceeded fairly slowly. Up to the 14th century there are fewer Persian inscriptions than Arabic. It must be stressed that there are few known versions of the latter, but they were very often reproduced on objects.

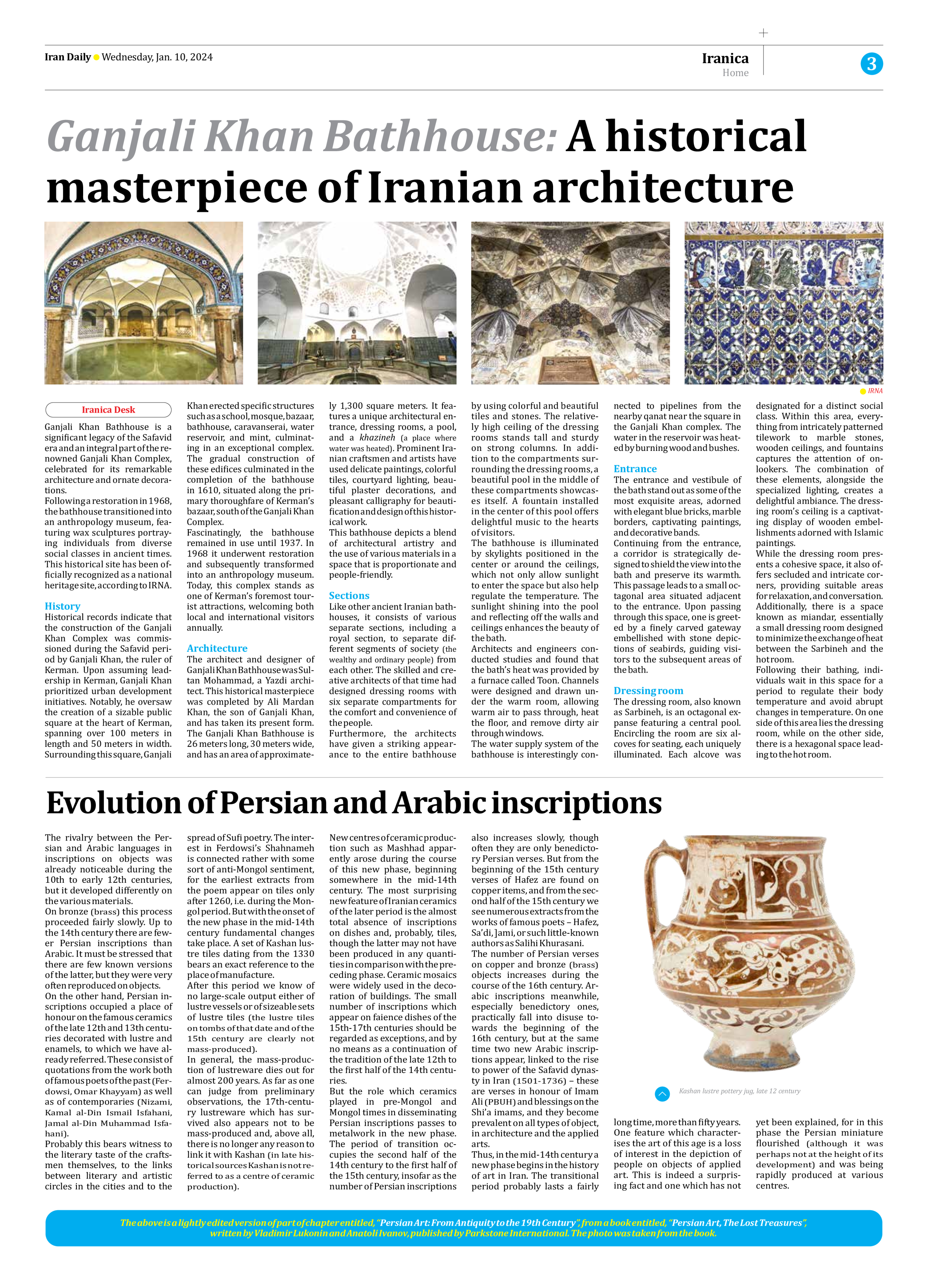

On the other hand, Persian inscriptions occupied a place of honour on the famous ceramics of the late 12th and 13th centuries decorated with lustre and enamels, to which we have already referred. These consist of quotations from the work both of famous poets of the past (Ferdowsi, Omar Khayyam) as well as of contemporaries (Nizami, Kamal al-Din Ismail Isfahani, Jamal al-Din Muhammad Isfahani).

Probably this bears witness to the literary taste of the craftsmen themselves, to the links between literary and artistic circles in the cities and to the spread of Sufi poetry. The interest in Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh is connected rather with some sort of anti-Mongol sentiment, for the earliest extracts from the poem appear on tiles only after 1260, i.e. during the Mongol period. But with the onset of the new phase in the mid-14th century fundamental changes take place. A set of Kashan lustre tiles dating from the 1330 bears an exact reference to the place of manufacture.

After this period we know of no large-scale output either of lustre vessels or of sizeable sets of lustre tiles (the lustre tiles on tombs of that date and of the 15th century are clearly not mass-produced).

In general, the mass-production of lustreware dies out for almost 200 years. As far as one can judge from preliminary observations, the 17th-century lustreware which has survived also appears not to be mass-produced and, above all, there is no longer any reason to link it with Kashan (in late historical sources Kashan is not referred to as a centre of ceramic production).

New centres of ceramic production such as Mashhad apparently arose during the course of this new phase, beginning somewhere in the mid-14th century. The most surprising new feature of Iranian ceramics of the later period is the almost total absence of inscriptions on dishes and, probably, tiles, though the latter may not have been produced in any quantities in comparison with the preceding phase. Ceramic mosaics were widely used in the decoration of buildings. The small number of inscriptions which appear on faience dishes of the 15th-17th centuries should be regarded as exceptions, and by no means as a continuation of the tradition of the late 12th to the first half of the 14th centuries.

But the role which ceramics played in pre-Mongol and Mongol times in disseminating Persian inscriptions passes to metalwork in the new phase. The period of transition occupies the second half of the 14th century to the first half of the 15th century, insofar as the number of Persian inscriptions also increases slowly, though often they are only benedictory Persian verses. But from the beginning of the 15th century verses of Hafez are found on copper items, and from the second half of the 15th century we see numerous extracts from the works of famous poets – Hafez, Sa’di, ]ami, or such little-known authors as Salihi Khurasani.

The number of Persian verses on copper and bronze (brass) objects increases during the course of the 16th century. Arabic inscriptions meanwhile, especially benedictory ones, practically fall into disuse towards the beginning of the 16th century, but at the same time two new Arabic inscriptions appear, linked to the rise to power of the Safavid dynasty in Iran (1501-1736) – these are verses in honour of Imam Ali (PBUH) and blessings on the Shi’a imams, and they become prevalent on all types of object, in architecture and the applied arts.

Thus, in the mid-14th century a new phase begins in the history of art in Iran. The transitional period probably lasts a fairly long time, more than fifty years.

One feature which characterises the art of this age is a loss of interest in the depiction of people on objects of applied art. This is indeed a surprising fact and one which has not yet been explained, for in this phase the Persian miniature flourished (although it was perhaps not at the height of its development) and was being rapidly produced at various centres.

The above is a lightly edited version of part of chapter entitled, “Persian Art: From Antiquity to the 19th Century”, from a book entitled, “Persian Art, The Lost Treasures”,

written by Vladimir Lukonin and Anatoli Ivanov, published by Parkstone International. The photo was taken from the book.