The great Iranian culture is being born

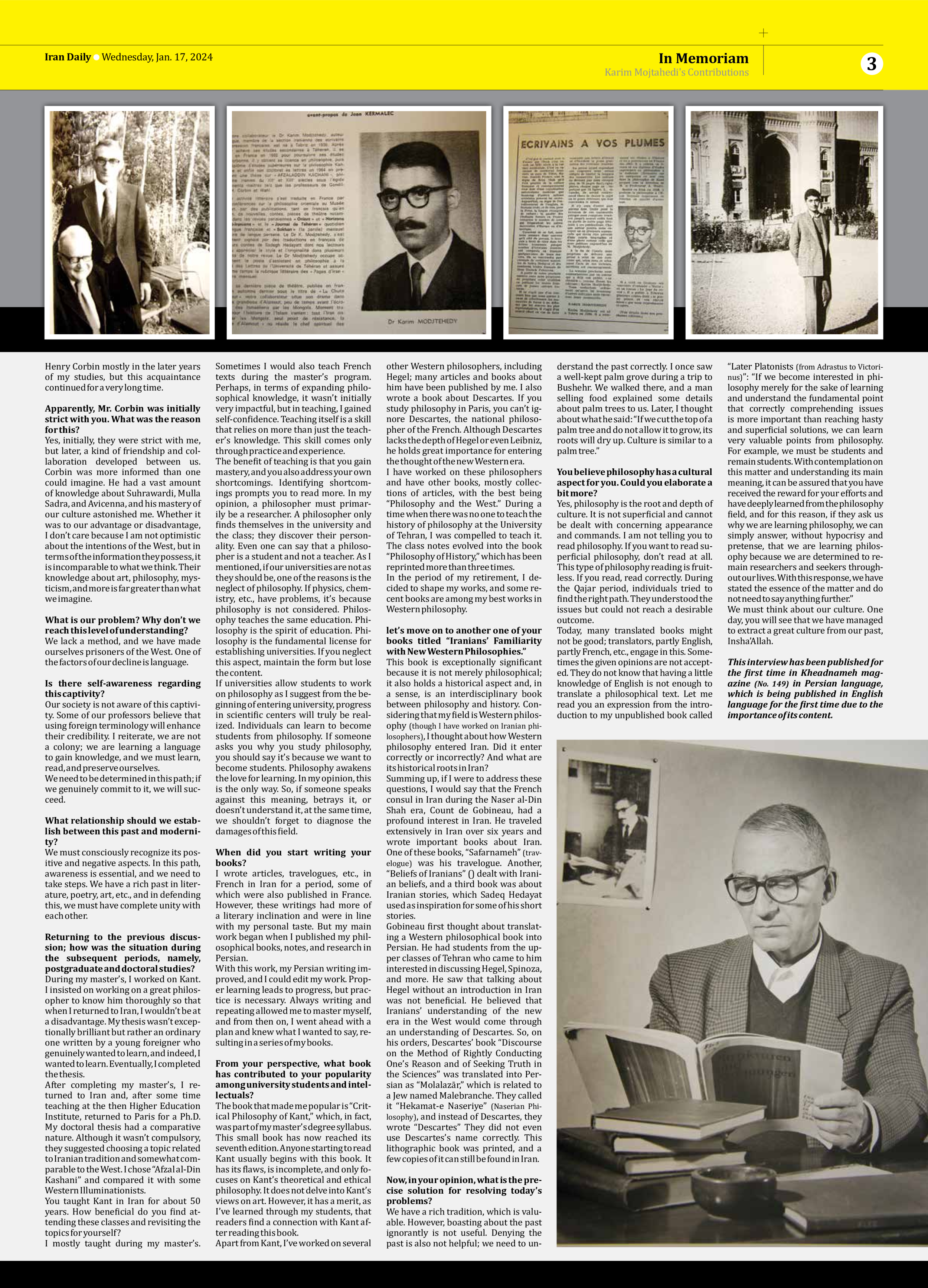

Unpublished interview with Professor Karim Mojtahedi

Journalists

As you mentioned, prior to the interview, we reviewed your works and consulted with your associates about where to begin the interview with Dr. Karim Mojtahedi and what topic to focus on. However, please elaborate on the reason for emphasizing this particular topic.

To provide some clarity, I would like to express that, in this interview, I prefer to discuss more about my works and books. I have dedicated my entire life to philosophical pursuits, and the culmination of these endeavors is the books that are available to you today. I wish for the perception of me in people’s minds to be associated not with myself but with my works. This is not driven by a desire for commercial success but rather a genuine interest in having my books read and evaluated, revealing their strengths and weaknesses for my own understanding. This, to me, is more important than anything else.

Given your suggestion to focus more on philosophy and your books, if you permit, I propose dividing the interview into two sections. In the first part, we can briefly discuss your background and biography, and then transition to the main topic of interest, which is your preferred discussion. Please provide a concise overview of your life before going to France.

I was born in Tabriz, but I mostly grew up in Tehran from childhood, even completing my elementary education there. My family was relatively well-known; my grandfather, Mirza Javad Mojtahedi, is mentioned in history books and even in high school textbooks. He was a clergyman who played a significant role in the tobacco boycott in Azerbaijan. In a letter written by Seyed Jamal al-Din Asadabadi to Mirza Shirazi, his name is mentioned second after Mirza Shirazi.

At the age of eighteen, I completed my secondary education at Firouzbahram and Alborz College, then went to Paris for further studies. I spent my entire university education there, from the beginning to the end. I won’t claim it was easy; on the contrary, I was a typical wandering Iranian student who hadn’t acquired the necessary skills to attend French classes yet chose philosophy from the outset.

You are quite young, and perhaps you are unaware that after World War II, there was a prevalent atmosphere of political and cultural discussions in Tehran, with various political parties present, and numerous books were being written. Looking back, those writings lack substantial content, but they created a certain atmosphere of debate and criticism in Tehran, giving rise to individuals like me. During that period, influenced by this debate atmosphere, most young people inclined towards technical fields for their studies.

Anyone aspiring for academic advancement would pursue medicine or engineering, and if not, they would lean towards law. What led you to deviate from this trend?

I pursued my academic field based on my personal choice, despite my family’s disapproval. I believed we didn’t all have to conform and follow the same path, becoming engineers, doctors, or lawyers in the conventional sense of that time. I constantly questioned what significance these intellectual debates and diverse opinions held, and what the political parties really had to say. I thought philosophy might offer suitable answers to these questions, which is why I was already an avid reader. I remember reading twelve books during a ten-day pilgrimage trip to Mashhad.

The high school environment also nudged me in this direction. Admittedly, there was an element of idealism, and I won’t deny it. I thought studying philosophy would lead me to find a path distinct from others, one with greater authenticity. However, when I went to France and began studying philosophy, I realized how naive I had been. I thought philosophy would be an easy discipline, but it turned out to be the opposite. For an Iranian at that time, any field other than philosophy seemed easier because they all had established curricula to follow, whereas in philosophy, there was no plan in the first year, and one had to have an innate aptitude for the subject.

Nevertheless, I passed the first-year general exam “propedeutique” at Sorbonne University, which was not competitive but necessary for admission. At that time, I was the only Iranian who had passed this exam. Perhaps, the reason for my acceptance was that I was a methodical person, always contemplating how to study to get the highest grades. For instance, in an English written exam, I memorized words with incorrect pronunciation so that I could write them correctly in the written exam.

How were the living conditions during that time?

Those two years were quite challenging for me, especially as it was during the Mossadegh era, and we didn’t receive foreign currency. Most of us were financially strapped, facing various issues, but fortunately, there were ample facilities for students at that time. It wasn’t complete luxury, but there were at least basic amenities available. We would get coupons and have a low-cost meal at university restaurants, but with the same amount of money, we couldn’t even afford a cup of tea outside.

Of course, in some cases, facilities were nonexistent. For example, there was no heater in my room throughout the winter. I remember in the winter, while reading a book, I would place a small part of my hand outside just to be able to hold the book. After those two difficult years, I had a better understanding. I became more familiar with the situation and knew what to do. In the first two years, I was impulsive, like someone who didn’t know what career path they wanted to pursue.

To complete the philosophy bachelor’s degree, we had to take written exams in psychology, social logic, ethics, history of philosophy, and philosophy of science. These were our main courses, and none of them were taught directly. The teaching method involved a professor coming to class and, for example, discussing only Descartes regarding the history of philosophy. This was challenging for me as an Iranian who wasn’t accustomed to this teaching style.

The Sorbonne library was open until 10 PM. If I didn’t have a heater at home, the library was a warm and comfortable alternative. We would stay in the library until 10 PM, and the necessary books were accessible. Reference books were free to use within the library, and there was no need to ask for permission. Everyone was focused on learning, and the eagerness to learn was palpable. Despite the large hall, sometimes it was challenging to find a seat. People would queue in front of the library, waiting for a spot.

In your opinion, how did this atmosphere affect the quality of education and the elevation of individuals?

This atmosphere is influential in itself. In an environment where there is eagerness to learn, the individual becomes eager as well, similar to a wolf that is seated and eating. Most students were eager for knowledge. It wasn’t easy to ask someone a question because everyone was busy learning. This atmosphere had an impact on my Iranian identity. I learned the eagerness for learning from that university. Even now, with not being in good physical condition, I read as much as I can. I live my life through work and philosophical thinking.

In Europe, I had the mentality that I am Iranian and must serve Iran, considering learning as my duty. The drive to learn came from within. This sense itself created a duty towards compatriots, the homeland, and the family. Alongside these, you also find a duty towards yourself, not in a prideful sense, saying that I am superior, but acknowledging that I am inferior and must address my intellectual deficiencies.

You must tell yourself that I am learning so that I stay away from ignorance because if I remain ignorant, I have done injustice to myself. To be just, I must stay away from ignorance. This duty an individual feels towards themselves in philosophy should be a foundation for creating a personality with intellectual and spiritual independence. A philosopher must be self-reliant and have confidence in their own thinking.

During this time, who were your renowned professors?

My professors were significant figures such as Jean Wahl, Georges Gurvitch, Jean Piaget, and many others.

During this period, you had interactions with H Henry Corbin, is that correct?

I became more acquainted with Henry Corbin mostly in the later years of my studies, but this acquaintance continued for a very long time.

Apparently, Mr. Corbin was initially strict with you. What was the reason for this?

Yes, initially, they were strict with me, but later, a kind of friendship and collaboration developed between us. Corbin was more informed than one could imagine. He had a vast amount of knowledge about Suhrawardi, Mulla Sadra, and Avicenna, and his mastery of our culture astonished me. Whether it was to our advantage or disadvantage, I don’t care because I am not optimistic about the intentions of the West, but in terms of the information they possess, it is incomparable to what we think. Their knowledge about art, philosophy, mysticism, and more is far greater than what we imagine.

What is our problem? Why don’t we reach this level of understanding?

We lack a method, and we have made ourselves prisoners of the West. One of the factors of our decline is language.

Is there self-awareness regarding this captivity?

Our society is not aware of this captivity. Some of our professors believe that using foreign terminology will enhance their credibility. I reiterate, we are not a colony; we are learning a language to gain knowledge, and we must learn, read, and preserve ourselves.

We need to be determined in this path; if we genuinely commit to it, we will succeed.

What relationship should we establish between this past and modernity?

We must consciously recognize its positive and negative aspects. In this path, awareness is essential, and we need to take steps. We have a rich past in literature, poetry, art, etc., and in defending this, we must have complete unity with each other.

Returning to the previous discussion; how was the situation during the subsequent periods, namely, postgraduate and doctoral studies?

During my master’s, I worked on Kant. I insisted on working on a great philosopher to know him thoroughly so that when I returned to Iran, I wouldn’t be at a disadvantage. My thesis wasn’t exceptionally brilliant but rather an ordinary one written by a young foreigner who genuinely wanted to learn, and indeed, I wanted to learn. Eventually, I completed the thesis.

After completing my master’s, I returned to Iran and, after some time teaching at the then Higher Education Institute, returned to Paris for a Ph.D. My doctoral thesis had a comparative nature. Although it wasn’t compulsory, they suggested choosing a topic related to Iranian tradition and somewhat comparable to the West. I chose “Afzal al-Din Kashani” and compared it with some Western Illuminationists.

You taught Kant in Iran for about 50 years. How beneficial do you find attending these classes and revisiting the topics for yourself?

I mostly taught during my master’s. Sometimes I would also teach French texts during the master’s program. Perhaps, in terms of expanding philosophical knowledge, it wasn’t initially very impactful, but in teaching, I gained self-confidence. Teaching itself is a skill that relies on more than just the teacher’s knowledge. This skill comes only through practice and experience.

The benefit of teaching is that you gain mastery, and you also address your own shortcomings. Identifying shortcomings prompts you to read more. In my opinion, a philosopher must primarily be a researcher. A philosopher only finds themselves in the university and the class; they discover their personality. Even one can say that a philosopher is a student and not a teacher. As I mentioned, if our universities are not as they should be, one of the reasons is the neglect of philosophy. If physics, chemistry, etc., have problems, it’s because philosophy is not considered. Philosophy teaches the same education. Philosophy is the spirit of education. Philosophy is the fundamental license for establishing universities. If you neglect this aspect, maintain the form but lose the content.

If universities allow students to work on philosophy as I suggest from the beginning of entering university, progress in scientific centers will truly be realized. Individuals can learn to become students from philosophy. If someone asks you why you study philosophy, you should say it’s because we want to become students. Philosophy awakens the love for learning. In my opinion, this is the only way. So, if someone speaks against this meaning, betrays it, or doesn’t understand it, at the same time, we shouldn’t forget to diagnose the damages of this field.

When did you start writing your books?

I wrote articles, travelogues, etc., in French in Iran for a period, some of which were also published in France. However, these writings had more of a literary inclination and were in line with my personal taste. But my main work began when I published my philosophical books, notes, and research in Persian.

With this work, my Persian writing improved, and I could edit my work. Proper learning leads to progress, but practice is necessary. Always writing and repeating allowed me to master myself, and from then on, I went ahead with a plan and knew what I wanted to say, resulting in a series of my books.

From your perspective, what book has contributed to your popularity among university students and intellectuals?

The book that made me popular is “Critical Philosophy of Kant,” which, in fact, was part of my master’s degree syllabus. This small book has now reached its seventh edition. Anyone starting to read Kant usually begins with this book. It has its flaws, is incomplete, and only focuses on Kant’s theoretical and ethical philosophy. It does not delve into Kant’s views on art. However, it has a merit, as I’ve learned through my students, that readers find a connection with Kant after reading this book.

Apart from Kant, I’ve worked on several other Western philosophers, including Hegel; many articles and books about him have been published by me. I also wrote a book about Descartes. If you study philosophy in Paris, you can’t ignore Descartes, the national philosopher of the French. Although Descartes lacks the depth of Hegel or even Leibniz, he holds great importance for entering the thought of the new Western era.

I have worked on these philosophers and have other books, mostly collections of articles, with the best being “Philosophy and the West.” During a time when there was no one to teach the history of philosophy at the University of Tehran, I was compelled to teach it. The class notes evolved into the book “Philosophy of History,” which has been reprinted more than three times.

In the period of my retirement, I decided to shape my works, and some recent books are among my best works in Western philosophy.

let’s move on to another one of your books titled “Iranians’ Familiarity with New Western Philosophies.”

This book is exceptionally significant because it is not merely philosophical; it also holds a historical aspect and, in a sense, is an interdisciplinary book between philosophy and history. Considering that my field is Western philosophy (though I have worked on Iranian philosophers), I thought about how Western philosophy entered Iran. Did it enter correctly or incorrectly? And what are its historical roots in Iran?

Summing up, if I were to address these questions, I would say that the French consul in Iran during the Naser al-Din Shah era, Count de Gobineau, had a profound interest in Iran. He traveled extensively in Iran over six years and wrote important books about Iran. One of these books, “Safarnameh” (travelogue) was his travelogue. Another, “Beliefs of Iranians” () dealt with Iranian beliefs, and a third book was about Iranian stories, which Sadeq Hedayat used as inspiration for some of his short stories.

Gobineau first thought about translating a Western philosophical book into Persian. He had students from the upper classes of Tehran who came to him interested in discussing Hegel, Spinoza, and more. He saw that talking about Hegel without an introduction in Iran was not beneficial. He believed that Iranians’ understanding of the new era in the West would come through an understanding of Descartes. So, on his orders, Descartes’ book “Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting One’s Reason and of Seeking Truth in the Sciences” was translated into Persian as “Molalazār,” which is related to a Jew named Malebranche. They called it “Hekamat-e Naseriye” (Naserian Philosophy), and instead of Descartes, they wrote “Descartes” They did not even use Descartes’s name correctly. This lithographic book was printed, and a few copies of it can still be found in Iran.

Now, in your opinion, what is the precise solution for resolving today’s problems?

We have a rich tradition, which is valuable. However, boasting about the past ignorantly is not useful. Denying the past is also not helpful; we need to understand the past correctly. I once saw a well-kept palm grove during a trip to Bushehr. We walked there, and a man selling food explained some details about palm trees to us. Later, I thought about what he said: “If we cut the top of a palm tree and do not allow it to grow, its roots will dry up. Culture is similar to a palm tree.”

You believe philosophy has a cultural aspect for you. Could you elaborate a bit more?

Yes, philosophy is the root and depth of culture. It is not superficial and cannot be dealt with concerning appearance and commands. I am not telling you to read philosophy. If you want to read superficial philosophy, don’t read at all. This type of philosophy reading is fruitless. If you read, read correctly. During the Qajar period, individuals tried to find the right path. They understood the issues but could not reach a desirable outcome.

Today, many translated books might not be good; translators, partly English, partly French, etc., engage in this. Sometimes the given opinions are not accepted. They do not know that having a little knowledge of English is not enough to translate a philosophical text. Let me read you an expression from the introduction to my unpublished book called “Later Platonists (from Adrastus to Victorinus)”: “If we become interested in philosophy merely for the sake of learning and understand the fundamental point that correctly comprehending issues is more important than reaching hasty and superficial solutions, we can learn very valuable points from philosophy. For example, we must be students and remain students. With contemplation on this matter and understanding its main meaning, it can be assured that you have received the reward for your efforts and have deeply learned from the philosophy field, and for this reason, if they ask us why we are learning philosophy, we can simply answer, without hypocrisy and pretense, that we are learning philosophy because we are determined to remain researchers and seekers throughout our lives. With this response, we have stated the essence of the matter and do not need to say anything further.”

We must think about our culture. One day, you will see that we have managed to extract a great culture from our past, Insha’Allah.

This interview has been published for the first time in Kheadnameh magazine (No. 149) in Persian language, which is being published in English language for the first time due to the importance of its content.