UAE’s claims over Persian Gulf’s three islands

Historical sovereignty, colonial interventions, and int’l law perspectives

By MohammadMehdi

Seyed Nasseri

Researcher at SBU’s Center for Medical Ethics and Law Studies

The repeated assertions by the United Arab Emirates (UAE) during joint Arab meetings with China, Russia, and the European Union reveal multiple dimensions of a meticulously crafted strategy by the sheikhdoms of the southern Persian Gulf. Part of this strategy aims to exploit tensions between Iran and the West to garner support for unfounded claims over the Iranian islands, while another component seeks backing for Abu Dhabi’s positions in exchange for economic incentives extended to actors such as China, Russia, and Europe. Some experts suggest that, in the next phase, the UAE may turn to international bodies, including the United Nations Security Council and the International Court of Justice.

Accordingly, scrutinizing and responding to the UAE’s claims is of undeniable and critical importance. Following the occupation of the three islands by the United Kingdom, London attempted to negate Iran’s historical sovereignty over the islands, citing legal principles such as the “prior occupation” rule to justify its own control. The UK also asserted that it had occupied ungoverned islands.

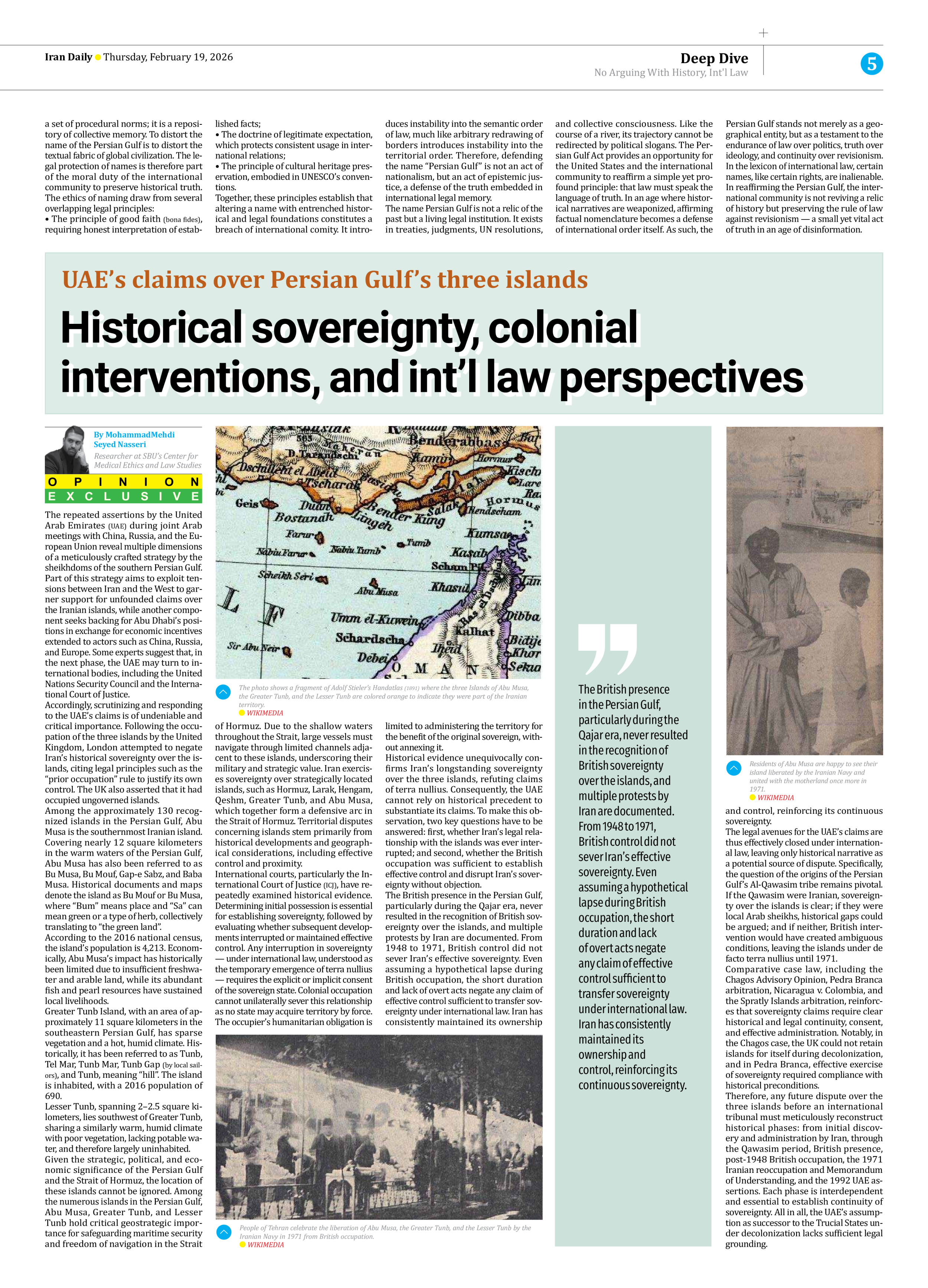

Among the approximately 130 recognized islands in the Persian Gulf, Abu Musa is the southernmost Iranian island. Covering nearly 12 square kilometers in the warm waters of the Persian Gulf, Abu Musa has also been referred to as Bu Musa, Bu Mouf, Gap-e Sabz, and Baba Musa. Historical documents and maps denote the island as Bu Mouf or Bu Musa, where “Bum” means place and “Sa” can mean green or a type of herb, collectively translating to “the green land”.

According to the 2016 national census, the island’s population is 4,213. Economically, Abu Musa’s impact has historically been limited due to insufficient freshwater and arable land, while its abundant fish and pearl resources have sustained local livelihoods.

Greater Tunb Island, with an area of approximately 11 square kilometers in the southeastern Persian Gulf, has sparse vegetation and a hot, humid climate. Historically, it has been referred to as Tunb, Tel Mar, Tunb Mar, Tunb Gap (by local sailors), and Tunb, meaning “hill”. The island is inhabited, with a 2016 population of 690.

Lesser Tunb, spanning 2–2.5 square kilometers, lies southwest of Greater Tunb, sharing a similarly warm, humid climate with poor vegetation, lacking potable water, and therefore largely uninhabited.

Given the strategic, political, and economic significance of the Persian Gulf and the Strait of Hormuz, the location of these islands cannot be ignored. Among the numerous islands in the Persian Gulf, Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, and Lesser Tunb hold critical geostrategic importance for safeguarding maritime security and freedom of navigation in the Strait of Hormuz. Due to the shallow waters throughout the Strait, large vessels must navigate through limited channels adjacent to these islands, underscoring their military and strategic value. Iran exercises sovereignty over strategically located islands, such as Hormuz, Larak, Hengam, Qeshm, Greater Tunb, and Abu Musa, which together form a defensive arc in the Strait of Hormuz. Territorial disputes concerning islands stem primarily from historical developments and geographical considerations, including effective control and proximity.

International courts, particularly the International Court of Justice (ICJ), have repeatedly examined historical evidence. Determining initial possession is essential for establishing sovereignty, followed by evaluating whether subsequent developments interrupted or maintained effective control. Any interruption in sovereignty — under international law, understood as the temporary emergence of terra nullius — requires the explicit or implicit consent of the sovereign state. Colonial occupation cannot unilaterally sever this relationship as no state may acquire territory by force. The occupier’s humanitarian obligation is limited to administering the territory for the benefit of the original sovereign, without annexing it.

Historical evidence unequivocally confirms Iran’s longstanding sovereignty over the three islands, refuting claims of terra nullius. Consequently, the UAE cannot rely on historical precedent to substantiate its claims. To make this observation, two key questions have to be answered: first, whether Iran’s legal relationship with the islands was ever interrupted; and second, whether the British occupation was sufficient to establish effective control and disrupt Iran’s sovereignty without objection.

The British presence in the Persian Gulf, particularly during the Qajar era, never resulted in the recognition of British sovereignty over the islands, and multiple protests by Iran are documented. From 1948 to 1971, British control did not sever Iran’s effective sovereignty. Even assuming a hypothetical lapse during British occupation, the short duration and lack of overt acts negate any claim of effective control sufficient to transfer sovereignty under international law. Iran has consistently maintained its ownership and control, reinforcing its continuous sovereignty.

The legal avenues for the UAE’s claims are thus effectively closed under international law, leaving only historical narrative as a potential source of dispute. Specifically, the question of the origins of the Persian Gulf’s Al-Qawasim tribe remains pivotal. If the Qawasim were Iranian, sovereignty over the islands is clear; if they were local Arab sheikhs, historical gaps could be argued; and if neither, British intervention would have created ambiguous conditions, leaving the islands under de facto terra nullius until 1971.

Comparative case law, including the Chagos Advisory Opinion, Pedra Branca arbitration, Nicaragua v. Colombia, and the Spratly Islands arbitration, reinforces that sovereignty claims require clear historical and legal continuity, consent, and effective administration. Notably, in the Chagos case, the UK could not retain islands for itself during decolonization, and in Pedra Branca, effective exercise of sovereignty required compliance with historical preconditions.

Therefore, any future dispute over the three islands before an international tribunal must meticulously reconstruct historical phases: from initial discovery and administration by Iran, through the Qawasim period, British presence, post-1948 British occupation, the 1971 Iranian reoccupation and Memorandum of Understanding, and the 1992 UAE assertions. Each phase is interdependent and essential to establish continuity of sovereignty. All in all, the UAE’s assumption as successor to the Trucial States under decolonization lacks sufficient legal grounding.