Tehran meeting offers chance to ease Afghanistan tensions

By Delaram Ahmadi

Staff writer

Seeking solutions for Afghanistan has been one of the top priorities of neighboring states and even Western governments over at least the past two decades. Security, terrorism, migration, narcotics, and the economy have formed the backbone of regional meetings, policy exchanges, and cooperative initiatives. Yet sharp disagreements persist among regional players, Afghanistan’s neighbors, and Western countries over the nature of governance in Afghanistan and how to engage with the current authorities in Kabul. These divergences, coupled with a prevailing security-centric approach, have made it difficult to arrive at a workable framework for addressing Afghanistan-related challenges.

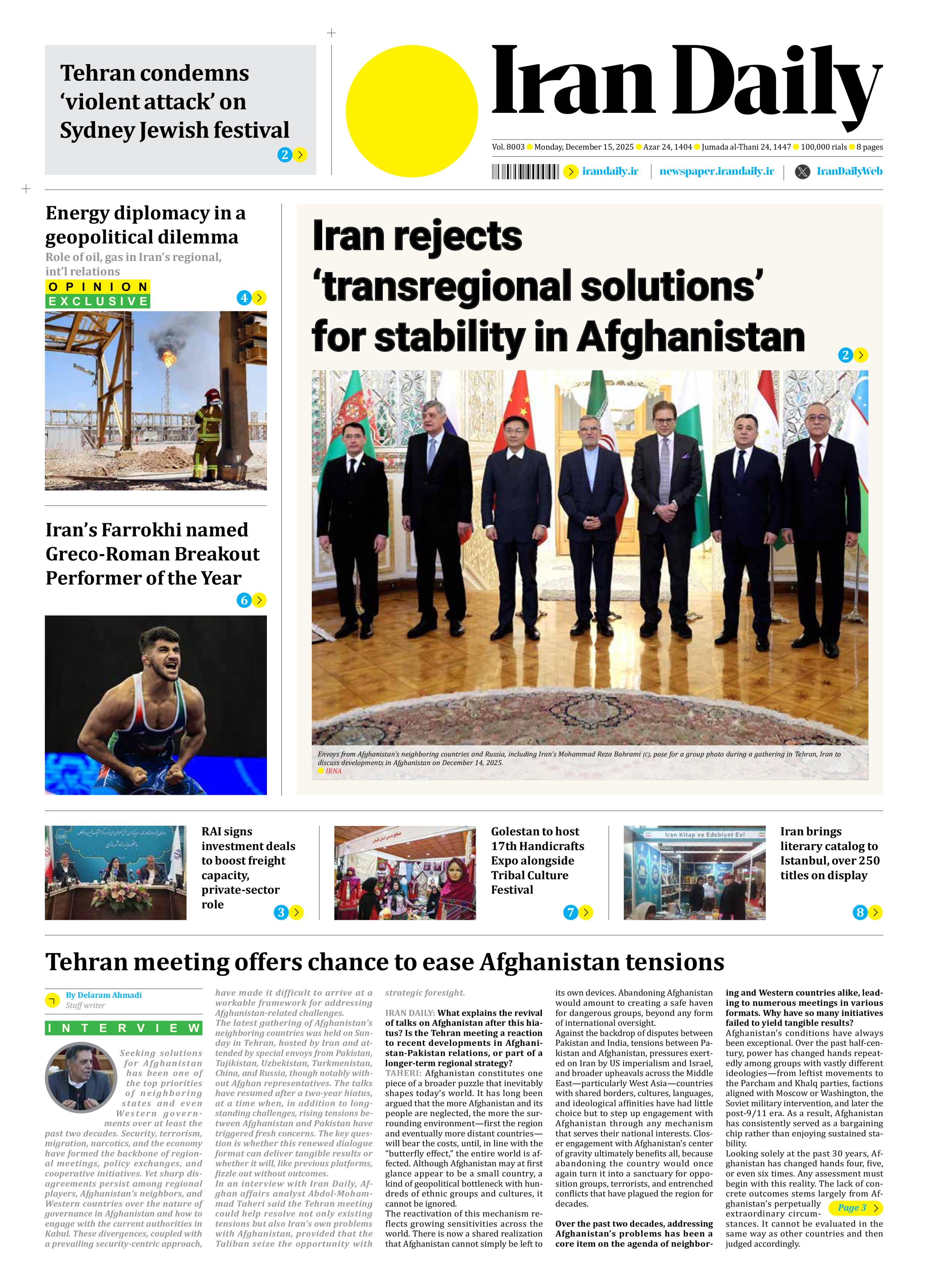

The latest gathering of Afghanistan’s neighboring countries was held on Sunday in Tehran, hosted by Iran and attended by special envoys from Pakistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, China, and Russia, though notably without Afghan representatives. The talks have resumed after a two-year hiatus, at a time when, in addition to longstanding challenges, rising tensions between Afghanistan and Pakistan have triggered fresh concerns. The key question is whether this renewed dialogue format can deliver tangible results or whether it will, like previous platforms, fizzle out without outcomes.

In an interview with Iran Daily, Afghan affairs analyst Abdol-Mohammad Taheri said the Tehran meeting could help resolve not only existing tensions but also Iran’s own problems with Afghanistan, provided that the Taliban seize the opportunity with strategic foresight.

IRAN DAILY: What explains the revival of talks on Afghanistan after this hiatus? Is the Tehran meeting a reaction to recent developments in Afghanistan-Pakistan relations, or part of a longer-term regional strategy?

TAHERI: Afghanistan constitutes one piece of a broader puzzle that inevitably shapes today’s world. It has long been argued that the more Afghanistan and its people are neglected, the more the surrounding environment—first the region and eventually more distant countries—will bear the costs, until, in line with the “butterfly effect,” the entire world is affected. Although Afghanistan may at first glance appear to be a small country, a kind of geopolitical bottleneck with hundreds of ethnic groups and cultures, it cannot be ignored.

The reactivation of this mechanism reflects growing sensitivities across the world. There is now a shared realization that Afghanistan cannot simply be left to its own devices. Abandoning Afghanistan would amount to creating a safe haven for dangerous groups, beyond any form of international oversight.

Against the backdrop of disputes between Pakistan and India, tensions between Pakistan and Afghanistan, pressures exerted on Iran by US imperialism and Israel, and broader upheavals across the Middle East—particularly West Asia—countries with shared borders, cultures, languages, and ideological affinities have had little choice but to step up engagement with Afghanistan through any mechanism that serves their national interests. Closer engagement with Afghanistan’s center of gravity ultimately benefits all, because abandoning the country would once again turn it into a sanctuary for opposition groups, terrorists, and entrenched conflicts that have plagued the region for decades.

Over the past two decades, addressing Afghanistan’s problems has been a core item on the agenda of neighboring and Western countries alike, leading to numerous meetings in various formats. Why have so many initiatives failed to yield tangible results?

Afghanistan’s conditions have always been exceptional. Over the past half-century, power has changed hands repeatedly among groups with vastly different ideologies—from leftist movements to the Parcham and Khalq parties, factions aligned with Moscow or Washington, the Soviet military intervention, and later the post-9/11 era. As a result, Afghanistan has consistently served as a bargaining chip rather than enjoying sustained stability.

Looking solely at the past 30 years, Afghanistan has changed hands four, five, or even six times. Any assessment must begin with this reality. The lack of concrete outcomes stems largely from Afghanistan’s perpetually extraordinary circumstances. It cannot be evaluated in the same way as other countries and then judged accordingly.

Page 3