Men, women practice centuries-old oil-making in Saqi village

Not so long ago, with the first cool waves of autumn sweeping down from the surrounding plains toward Saqi Village at the foot of the southern mountains of Gonabad, the unspoken calendar of village life quietly ushered in a new season. This was the season of preparation for the harsh winter ahead, and one of the most important symbols of this readiness was the “Autumn Oil-Making” ceremony.

Rooted in the subsistence economy and traditional family structures, this ritual was far more than a simple culinary activity — it was a full-fledged cultural manifesto.

The tradition was closely tied to the departure of the village men. The cold autumn and winter in Saqi compelled men to travel to the regional economic hub of Mashhad. These journeys were not merely for gathering the year’s essential provisions; they also served as an opportunity for social exchange and news from the outside world. The primary commodity sought was the fresh, white tail fat of sheep.

These tail fats were regarded as the village’s “autumn capital.” When the men returned laden with this vital resource, it marked the official start of the household season. This stage also reflected the traditional gender division of labor in Iranian families: men were responsible for procuring essential goods from the outside world, while women processed and transformed them within the safety of the home.

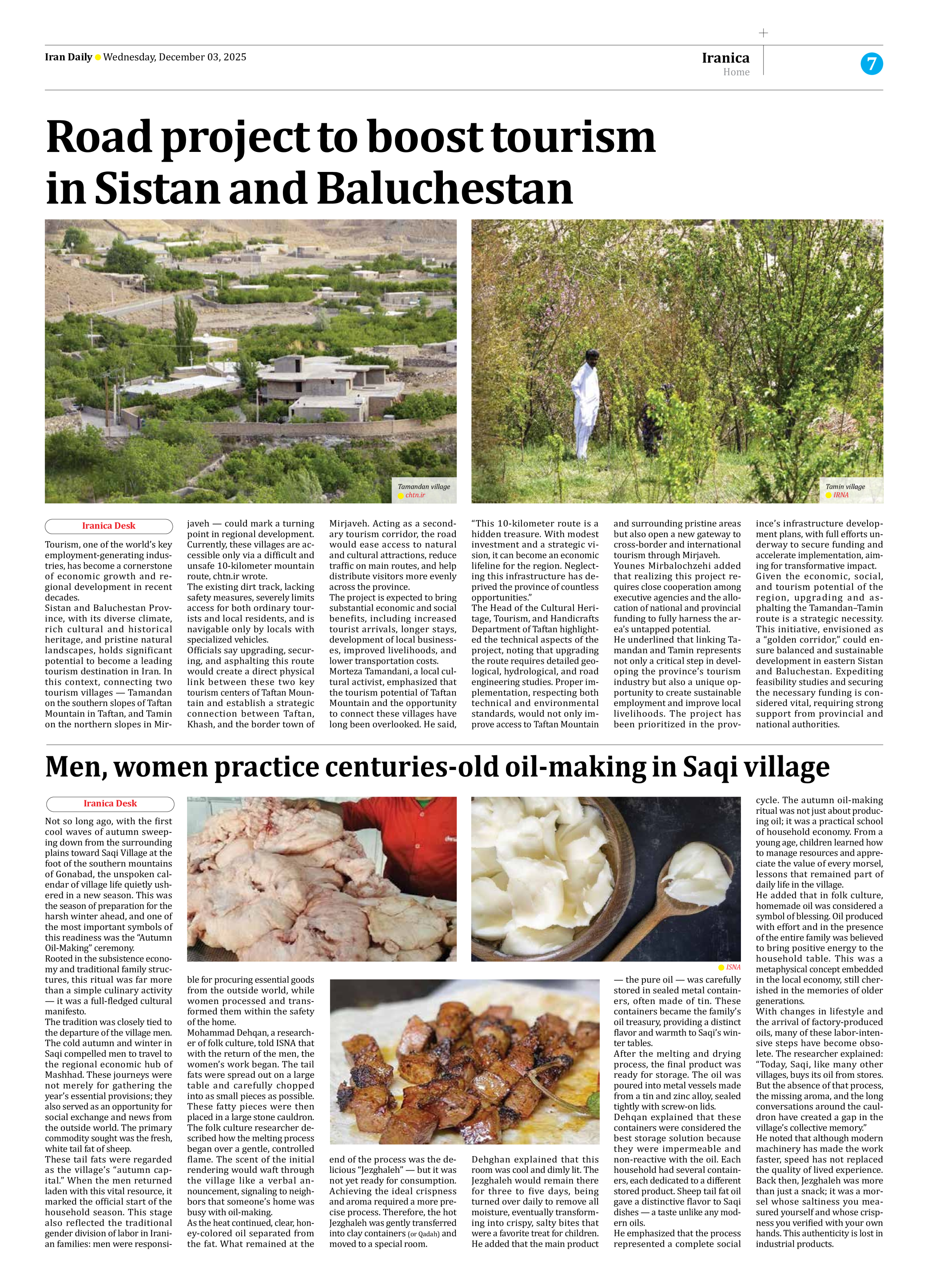

Mohammad Dehqan, a researcher of folk culture, told ISNA that with the return of the men, the women’s work began. The tail fats were spread out on a large table and carefully chopped into as small pieces as possible. These fatty pieces were then placed in a large stone cauldron.

The folk culture researcher described how the melting process began over a gentle, controlled flame. The scent of the initial rendering would waft through the village like a verbal announcement, signaling to neighbors that someone’s home was busy with oil-making.

As the heat continued, clear, honey-colored oil separated from the fat. What remained at the end of the process was the delicious “Jezghaleh” — but it was not yet ready for consumption. Achieving the ideal crispness and aroma required a more precise process. Therefore, the hot Jezghaleh was gently transferred into clay containers (or Qadah) and moved to a special room.

Dehghan explained that this room was cool and dimly lit. The Jezghaleh would remain there for three to five days, being turned over daily to remove all moisture, eventually transforming into crispy, salty bites that were a favorite treat for children.

He added that the main product — the pure oil — was carefully stored in sealed metal containers, often made of tin. These containers became the family’s oil treasury, providing a distinct flavor and warmth to Saqi’s winter tables.

After the melting and drying process, the final product was ready for storage. The oil was poured into metal vessels made from a tin and zinc alloy, sealed tightly with screw-on lids.

Dehqan explained that these containers were considered the best storage solution because they were impermeable and non-reactive with the oil. Each household had several containers, each dedicated to a different stored product. Sheep tail fat oil gave a distinctive flavor to Saqi dishes — a taste unlike any modern oils.

He emphasized that the process represented a complete social cycle. The autumn oil-making ritual was not just about producing oil; it was a practical school of household economy. From a young age, children learned how to manage resources and appreciate the value of every morsel, lessons that remained part of daily life in the village.

He added that in folk culture, homemade oil was considered a symbol of blessing. Oil produced with effort and in the presence of the entire family was believed to bring positive energy to the household table. This was a metaphysical concept embedded in the local economy, still cherished in the memories of older generations.

With changes in lifestyle and the arrival of factory-produced oils, many of these labor-intensive steps have become obsolete. The researcher explained: “Today, Saqi, like many other villages, buys its oil from stores. But the absence of that process, the missing aroma, and the long conversations around the cauldron have created a gap in the village’s collective memory.”

He noted that although modern machinery has made the work faster, speed has not replaced the quality of lived experience. Back then, Jezghaleh was more than just a snack; it was a morsel whose saltiness you measured yourself and whose crispness you verified with your own hands. This authenticity is lost in industrial products.