Humanity forsakes Enlightenment’s peace vision

By Morteza Golpoor

News editor at the political desk of Iran Newspaper

Has the primordial norm of human history been war or peace? Have human beings, throughout the ages, subsisted in serenity, or have they traversed most epochs in war with one another? Dr. Habibollah Fazeli and Dr. Jahangir Moeini Alamdari, two members of the faculty of Political Sciences at the University of Tehran, responded to these questions in a panel discussion entitled “War and Peace in Contemporary Political Thought,” convened on November 15 at the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of the University of Tehran.

In accordance with the expositions of Fazeli and Moeini Alamdari, the exclusive axiom of human history has been war rather than peace; even in the modern age, particularly in the 20th century, the number of wars — internal or interstate — has multiplied. The rationale for organizing this panel was that these two esteemed professors of political sciences, beyond presenting a historical narration and elucidation of war and peace, examine the scientific substrata, political and social causes, and even instinctual and cultural grounds of the eruption and proliferation of wars.

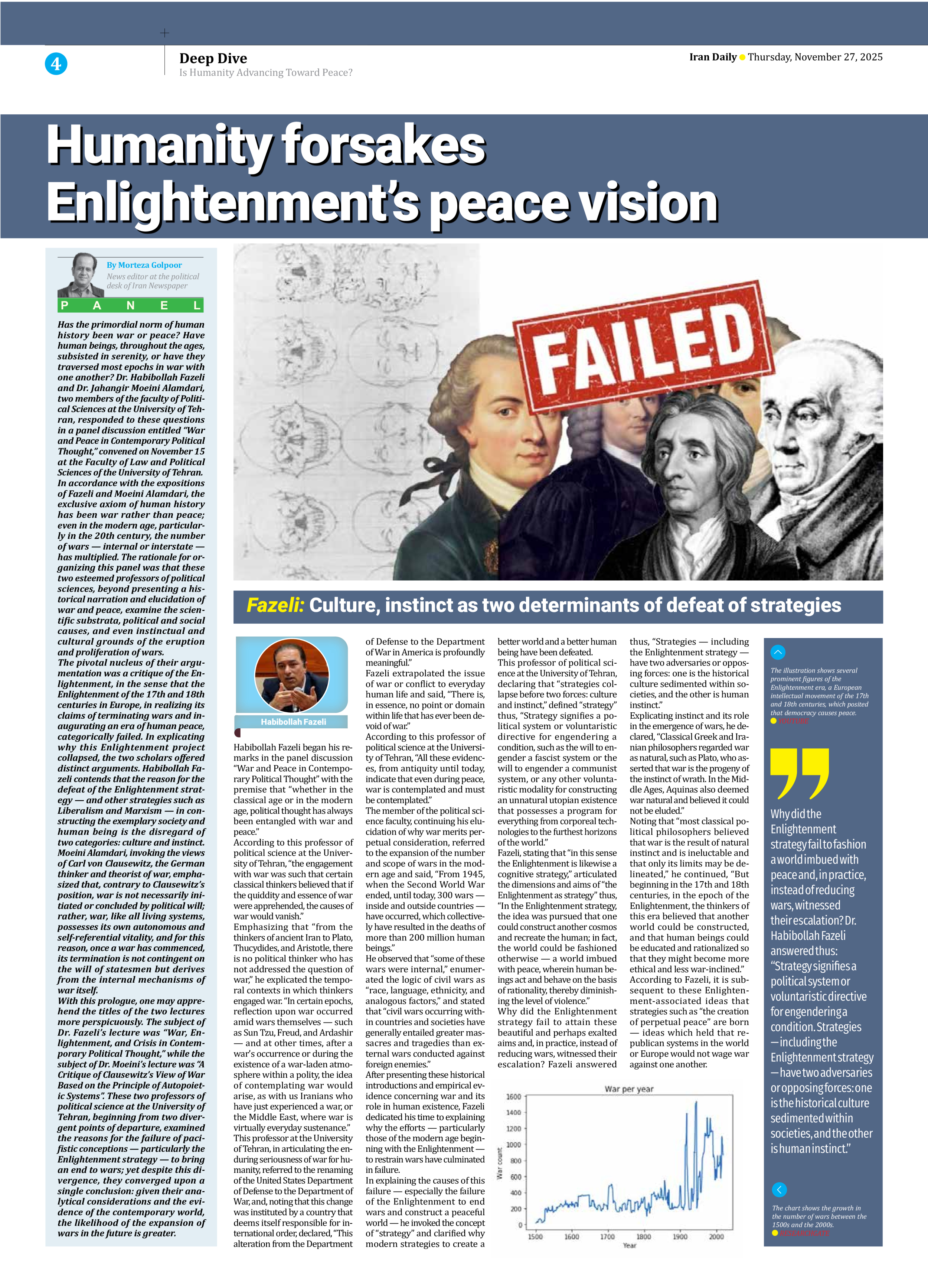

The pivotal nucleus of their argumentation was a critique of the Enlightenment, in the sense that the Enlightenment of the 17th and 18th centuries in Europe, in realizing its claims of terminating wars and inaugurating an era of human peace, categorically failed. In explicating why this Enlightenment project collapsed, the two scholars offered distinct arguments. Habibollah Fazeli contends that the reason for the defeat of the Enlightenment strategy — and other strategies such as Liberalism and Marxism — in constructing the exemplary society and human being is the disregard of two categories: culture and instinct. Moeini Alamdari, invoking the views of Carl von Clausewitz, the German thinker and theorist of war, emphasized that, contrary to Clausewitz’s position, war is not necessarily initiated or concluded by political will; rather, war, like all living systems, possesses its own autonomous and self-referential vitality, and for this reason, once a war has commenced, its termination is not contingent on the will of statesmen but derives from the internal mechanisms of war itself.

With this prologue, one may apprehend the titles of the two lectures more perspicuously. The subject of Dr. Fazeli’s lecture was “War, Enlightenment, and Crisis in Contemporary Political Thought,” while the subject of Dr. Moeini’s lecture was “A Critique of Clausewitz’s View of War Based on the Principle of Autopoietic Systems”. These two professors of political science at the University of Tehran, beginning from two divergent points of departure, examined the reasons for the failure of pacifistic conceptions — particularly the Enlightenment strategy — to bring an end to wars; yet despite this divergence, they converged upon a single conclusion: given their analytical considerations and the evidence of the contemporary world, the likelihood of the expansion of wars in the future is greater.

Fazeli: Culture, instinct as two determinants of defeat of strategies

Habibollah Fazeli

Habibollah Fazeli began his remarks in the panel discussion “War and Peace in Contemporary Political Thought” with the premise that “whether in the classical age or in the modern age, political thought has always been entangled with war and peace.”

According to this professor of political science at the University of Tehran, “the engagement with war was such that certain classical thinkers believed that if the quiddity and essence of war were apprehended, the causes of war would vanish.”

Emphasizing that “from the thinkers of ancient Iran to Plato, Thucydides, and Aristotle, there is no political thinker who has not addressed the question of war,” he explicated the temporal contexts in which thinkers engaged war. “In certain epochs, reflection upon war occurred amid wars themselves — such as Sun Tzu, Freud, and Ardashir — and at other times, after a war’s occurrence or during the existence of a war-laden atmosphere within a polity, the idea of contemplating war would arise, as with us Iranians who have just experienced a war, or the Middle East, where war is virtually everyday sustenance.”

This professor at the University of Tehran, in articulating the enduring seriousness of war for humanity, referred to the renaming of the United States Department of Defense to the Department of War, and, noting that this change was instituted by a country that deems itself responsible for international order, declared, “This alteration from the Department of Defense to the Department of War in America is profoundly meaningful.”

Fazeli extrapolated the issue of war or conflict to everyday human life and said, “There is, in essence, no point or domain within life that has ever been devoid of war.”

According to this professor of political science at the University of Tehran, “All these evidences, from antiquity until today, indicate that even during peace, war is contemplated and must be contemplated.”

The member of the political science faculty, continuing his elucidation of why war merits perpetual consideration, referred to the expansion of the number and scope of wars in the modern age and said, “From 1945, when the Second World War ended, until today, 300 wars — inside and outside countries — have occurred, which collectively have resulted in the deaths of more than 200 million human beings.”

He observed that “some of these wars were internal,” enumerated the logic of civil wars as “race, language, ethnicity, and analogous factors,” and stated that “civil wars occurring within countries and societies have generally entailed greater massacres and tragedies than external wars conducted against foreign enemies.”

After presenting these historical introductions and empirical evidence concerning war and its role in human existence, Fazeli dedicated his time to explaining why the efforts — particularly those of the modern age beginning with the Enlightenment — to restrain wars have culminated in failure.

In explaining the causes of this failure — especially the failure of the Enlightenment to end wars and construct a peaceful world — he invoked the concept of “strategy” and clarified why modern strategies to create a better world and a better human being have been defeated.

This professor of political science at the University of Tehran, declaring that “strategies collapse before two forces: culture and instinct,” defined “strategy” thus, “Strategy signifies a political system or voluntaristic directive for engendering a condition, such as the will to engender a fascist system or the will to engender a communist system, or any other voluntaristic modality for constructing an unnatural utopian existence that possesses a program for everything from corporeal technologies to the furthest horizons of the world.”

Fazeli, stating that “in this sense the Enlightenment is likewise a cognitive strategy,” articulated the dimensions and aims of “the Enlightenment as strategy” thus, “In the Enlightenment strategy, the idea was pursued that one could construct another cosmos and recreate the human; in fact, the world could be fashioned otherwise — a world imbued with peace, wherein human beings act and behave on the basis of rationality, thereby diminishing the level of violence.”

Why did the Enlightenment strategy fail to attain these beautiful and perhaps exalted aims and, in practice, instead of reducing wars, witnessed their escalation? Fazeli answered thus, “Strategies — including the Enlightenment strategy — have two adversaries or opposing forces: one is the historical culture sedimented within societies, and the other is human instinct.”

Explicating instinct and its role in the emergence of wars, he declared, “Classical Greek and Iranian philosophers regarded war as natural, such as Plato, who asserted that war is the progeny of the instinct of wrath. In the Middle Ages, Aquinas also deemed war natural and believed it could not be eluded.”

Noting that “most classical political philosophers believed that war is the result of natural instinct and is ineluctable and that only its limits may be delineated,” he continued, “But beginning in the 17th and 18th centuries, in the epoch of the Enlightenment, the thinkers of this era believed that another world could be constructed, and that human beings could be educated and rationalized so that they might become more ethical and less war-inclined.”

According to Fazeli, it is subsequent to these Enlightenment-associated ideas that strategies such as “the creation of perpetual peace” are born — ideas which held that republican systems in the world or Europe would not wage war against one another.

Referring to the fact that “the establishment of an international court, as Johann Gottlieb Fichte stated, or world peace as Emmanuel Kant articulated, and analogous ideas were all products of this Enlightenment strategy and its underlying vision,” he added, “The fact that political systems such as Communism, Fascism, or even Nazism sought to cultivate their desired human beings is also comprehensible within this framework; essentially, all such utopian logics believed that one could construct the exemplary or ethical human being and thereby halt war.”

Fazeli interpreted Carl von Clausewitz’s theory of war within the same framework of strategy and Enlightenment anthropology and said, “Clausewitz, as one of the most consequential theorists of war, conceives war as a forceful duel between two human beings and situates it within the continuation of politics and political logic, concluding that if we resolve the quandary of political logic, then war itself becomes controllable.”

Referring to the fact that “in the 17th and 18th centuries such claims were frequently propounded,” he explained that what definitively undermined Enlightenment ideas were the catastrophes and wars of the 20th century.

“In the 20th century — which was the era of culminations and the maturity of the Enlightenment and reason — thinkers expected the century to be the age of peace, for the aim of the Enlightenment was that with the proliferation of knowledge, human beings would become less war-inclined. Yet the wars that occurred were such that thinkers like Isaiah Berlin and Eric Hobsbawm designated the 20th century ‘the most terrible century,’ for nearly 200 million human beings were killed.”

Continuing this section of his discourse, he employed conceptual instruments to explain why such catastrophic wars transpired.

He began by noting, “What is profoundly noteworthy is that the slaughter of these millions in the 20th century lacked religious or theological meaning; rather, it was predicated on territorial ambition, language, race, and ethnicity.”

He remarked that “territorial ambition, language, race, and ethnicity are all modern concepts,” and once more posed the question: “Why did the 20th century — contrary to Enlightenment expectations — unfold not as the century of ethics and peace but otherwise?”

The political science professor answered, “One must seek the answer in two concepts: human instinct and the nature of the modern state.”

In explaining the role of instinct and the modern state in the defeat of the Enlightenment strategy, he declared, “The Enlightenment failed in both its aims, for it possessed no precise image of human instinct and substituted a beautiful and dreamlike image for the natural reality, and in addition fabricated a new political unit with a particular political identity — the nation-state — whose intrinsic essence is internal and external war.”

“Psychoanalytic and psychological research indicates that human beings desire war; yet the voluntarism of the Enlightenment, upon which Marxism and Fascism also relied, believed that one could, contrary to this instinct, construct another world or another human being.”

For this reason, Fazeli continued, “After 1945, when political thought attained greater maturity, many thinkers concentrated on the human psyche and emphasized that human beings desire war.”

Noting that “besides human instinct, the second determinant of the Enlightenment strategy’s defeat — and the cause of the great wars of the 20th century — is the modern state,” he articulated the relation of the modern state to war thus, “One must first clarify that the modern state is distinct from the national state. The national state is based upon the logic of myths, language, history, and culture; thus, one may assert that the national state has a natural logic, whereas the modern nation-state is grounded in contractual logic.”

He continued that, unlike the national state which is natural, “some thinkers believed that one could construct state and nation and fabricate for them identity and history,” and affirmed: “Thus, the new state is an artificial identity annexed to an army, and the political and identity disquietude of these modern states is one of the causes of the 20th century’s wars.”

He concluded: “The natural identity of national states means that these states are constituted upon two elements: the software element (historical identity) and the hardware element (geopolitics and access to water). They are ancient elements within modern forms. The fate of the Iranian national state in the Middle East is a quintessential exemplar of this analytical model. Conversely, the political units detached from Iran — such as Baku, the Kurdish region of the Middle East, Afghanistan, Armenia, Tajikistan, and other units — today suffer from both afflictions: identity disquietude and landlocked geography, and therefore their identities are intertwined with an intrinsic internal and external antagonism.”

Moeini: A critique of Clausewitz’s theory of war

Jahangir Moeini Alamdari

The second speaker of the panel discussion, Dr. Jahangir Moeini Alamdari, another member of the political science faculty, based his discussion upon a critique of Carl von Clausewitz’s theory of war and its relation to political volition, and, invoking Clausewitz’s idea that “war is an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will.,” presented alternative perspectives.

Moeini said, “In contrast to Clausewitz’s theory, some thinkers maintain that war is indefinable, for instead of a single war, we confront wars; postmodernists belong to this group. The second view, belonging to idealists, holds that war intrinsically signifies a condition of the absence of law and a state devoid of rule, and therefore cannot be explained or defined.”

Stating that “the third perspective philosophically diminishes the seriousness of speaking about war,” he added, “The third perspective argues that one cannot posit any substantive basis for war and that war must be regarded merely as an instrument in the service of politics, for it lacks independent logic and is defined solely by its relation to politics.”

Moeini Alamdari, declaring that “I oppose all three perspectives,” offered his rationale, “I do not believe that war is so dispersed that no unity can be found for it; nor do I believe that war must be conceived upon the basis of the absence of peace; and third, I do not believe that war is something subservient to politics or merely an instrument of the political realm.”

The professor of political science, stating that “from the Peloponnesian War in Greece to the 12-day Israeli war against Iran, all wars possess specific structures,” added, “I elucidate these structures through the internal logic of war itself and demonstrate that the logic of war is not interpretable by the logic of politics.”

Declaring that “my concern is not the origin of war, nor am I concerned with how war may be prevented,” he said, “My argument is that once war begins, its connection to politics is severed, and it exits the control of the political sphere and of statesmen. Therefore, one cannot, in practice, explain the logic of war using the language and logic of politics.”

After these introductory statements, Moeini explained that “whatever the reason for the outbreak of war is, in all wars, nevertheless, the logic of war is singular, and moreover, the logic of war becomes entirely distinct from the logic of politics.”

To explicate why the logic of war is autonomous and unrelated to politics, he invoked the theory of Autopoiesis in the biological sciences, which emerged in 1973.

He said, “Autopoiesis elucidates how a system, independent of its environment, commences self-replication and self-production, and explains that such a system requires no external factor for its continued development.”

Noting that “researchers in biology maintain that these systems — cellular and chromosomal replication — can generate ‘systems’ and require no external factor for their formation,” he articulated the nucleus of his own thesis thus, “Clausewitz’s claim that war is related to politics — that whenever a statesman wishes, he can initiate war, and whenever he wishes, he can end it — is incompatible with the autopoietic system, which is self-determining.”

Moeini affirmed, “If we accept that the concept or reality of war is an autopoietic system, then, contrary to Clausewitz, the relation between politics and war dissolves.”

“The further point is that these autopoietic systems persist independently of their environment or other systems, and thus, when a war begins, it cannot be readily controlled, managed, or directed by statesmen. In other words, the ‘logic of war’ determines its own conditions and transmits these conditions to the realm of politics, imposing determination upon it.”

In articulating the outcome of his discourse, Moeini stated, “Thus, Clausewitz’s idea that politics and war are connected renders the comprehension of war difficult. Clausewitz, by positing a relation between politics and war, situates war upon the path of the Enlightenment, and consequently, war is interpreted through the prism of reason and unreason, or the natural and the unnatural; whereas the theory of autopoiesis asserts that the ‘order of war’ emerges from within war itself, and no order — including political order — is imposed upon it.”

Offering another critique of Clausewitz’s perspective, he said, “Placing the concept of war within the duality of rationality and irrationality results in the immanent aims of war being explained through transcendent aims, and perhaps this very approach has been one cause of humanity’s failure to end war.”

In other words, Moeini added, “The cause of humanity’s defeat — and specifically the Enlightenment’s defeat — in restraining war is that war has been interpreted through a logic other than its own intrinsic logic, namely through reason, history, and analogous constructs, whereas war possesses its own internal logic and must be comprehended through that internal logic.”

Stating that adopting Clausewitz as the basis for interpreting war can lead to a misapprehension of war, he affirmed, “Whereas according to the autopoietic concept, war is self-governing and cannot be explained or defined through politics.”

The professor, emphasizing that “war is a ‘self-organizing’ phenomenon,” stated, “The fact that institutions of war emerge, and that these institutions operate independently of civil institutions, derives from this very self-organizing property of war, which is a momentous phenomenon.”

Moeini concluded this section by stating, “Yet despite all this, one question endures with undiminished force: so long as wars continue and no end is conceivable for them, if war is an autopoietic or self-regulated system, how can one wage war while disregarding its logic?”

The article first appeared in the

Persian-language Iran Newspaper.