Birth of first Iranian library of criminal sciences

A hall that revivifies history, delineates future in University of Tehran

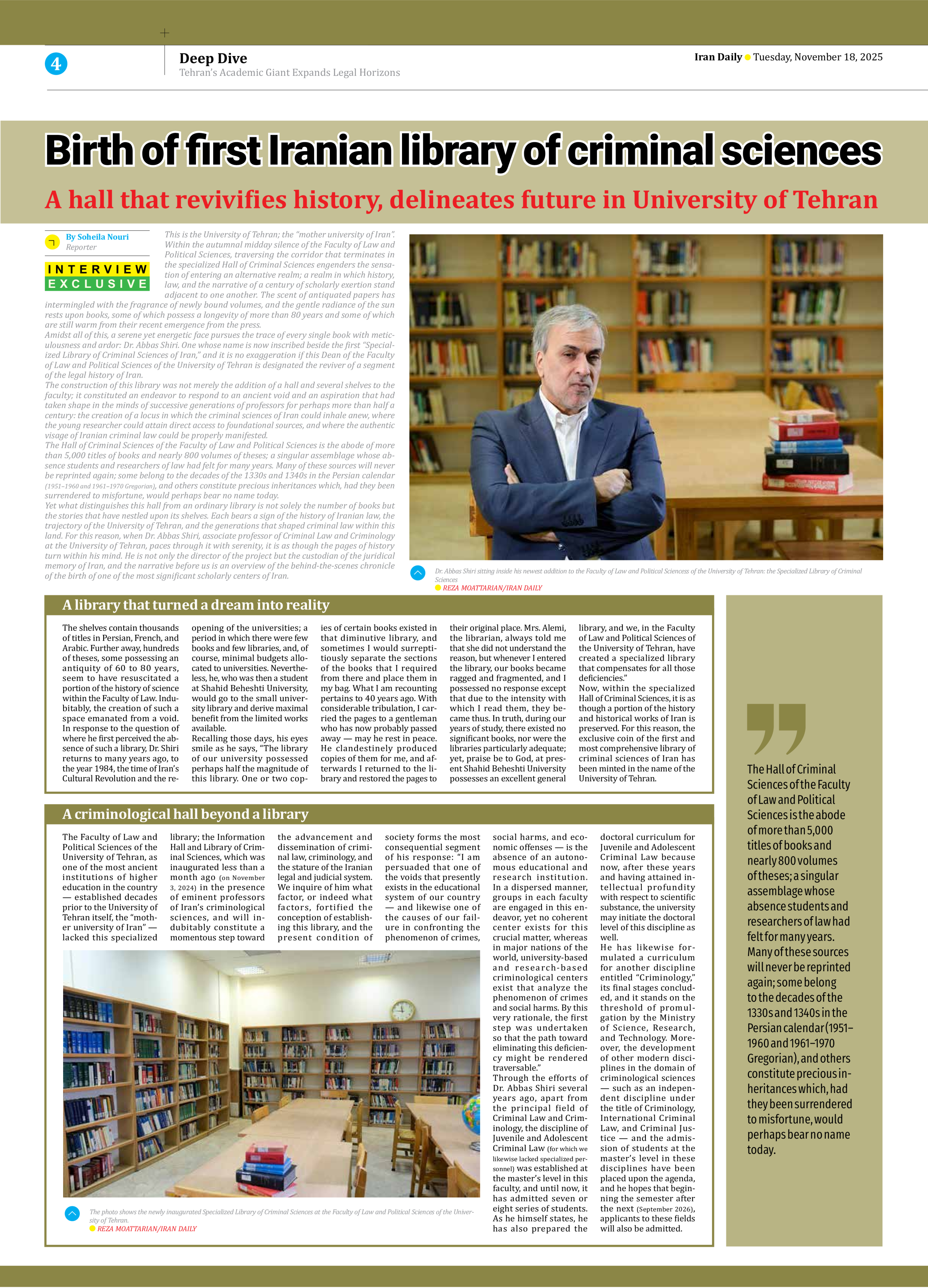

This is the University of Tehran; the “mother university of Iran”. Within the autumnal midday silence of the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences, traversing the corridor that terminates in the specialized Hall of Criminal Sciences engenders the sensation of entering an alternative realm; a realm in which history, law, and the narrative of a century of scholarly exertion stand adjacent to one another. The scent of antiquated papers has intermingled with the fragrance of newly bound volumes, and the gentle radiance of the sun rests upon books, some of which possess a longevity of more than 80 years and some of which are still warm from their recent emergence from the press. Amidst all of this, a serene yet energetic face pursues the trace of every single book with meticulousness and ardor: Dr. Abbas Shiri. One whose name is now inscribed beside the first “Specialized Library of Criminal Sciences of Iran,” and it is no exaggeration if this Dean of the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of the University of Tehran is designated the reviver of a segment of the legal history of Iran. The construction of this library was not merely the addition of a hall and several shelves to the faculty; it constituted an endeavor to respond to an ancient void and an aspiration that had taken shape in the minds of successive generations of professors for perhaps more than half a century: the creation of a locus in which the criminal sciences of Iran could inhale anew, where the young researcher could attain direct access to foundational sources, and where the authentic visage of Iranian criminal law could be properly manifested. The Hall of Criminal Sciences of the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences is the abode of more than 5,000 titles of books and nearly 800 volumes of theses; a singular assemblage whose absence students and researchers of law had felt for many years. Many of these sources will never be reprinted again; some belong to the decades of the 1330s and 1340s in the Persian calendar (1951–1960 and 1961–1970 Gregorian), and others constitute precious inheritances which, had they been surrendered to misfortune, would perhaps bear no name today. Yet what distinguishes this hall from an ordinary library is not solely the number of books but the stories that have nestled upon its shelves. Each bears a sign of the history of Iranian law, the trajectory of the University of Tehran, and the generations that shaped criminal law within this land. For this reason, when Dr. Abbas Shiri, associate professor of Criminal Law and Criminology at the University of Tehran, paces through it with serenity, it is as though the pages of history turn within his mind. He is not only the director of the project but the custodian of the juridical memory of Iran, and the narrative before us is an overview of the behind-the-scenes chronicle of the birth of one of the most significant scholarly centers of Iran.

By Soheila Nouri

Reporter

A library that turned a dream into reality

The shelves contain thousands of titles in Persian, French, and Arabic. Further away, hundreds of theses, some possessing an antiquity of 60 to 80 years, seem to have resuscitated a portion of the history of science within the Faculty of Law. Indubitably, the creation of such a space emanated from a void. In response to the question of where he first perceived the absence of such a library, Dr. Shiri returns to many years ago, to the year 1984, the time of Iran’s Cultural Revolution and the reopening of the universities; a period in which there were few books and few libraries, and, of course, minimal budgets allocated to universities. Nevertheless, he, who was then a student at Shahid Beheshti University, would go to the small university library and derive maximal benefit from the limited works available.

Recalling those days, his eyes smile as he says, “The library of our university possessed perhaps half the magnitude of this library. One or two copies of certain books existed in that diminutive library, and sometimes I would surreptitiously separate the sections of the books that I required from there and place them in my bag. What I am recounting pertains to 40 years ago. With considerable tribulation, I carried the pages to a gentleman who has now probably passed away — may he rest in peace. He clandestinely produced copies of them for me, and afterwards I returned to the library and restored the pages to their original place. Mrs. Alemi, the librarian, always told me that she did not understand the reason, but whenever I entered the library, our books became ragged and fragmented, and I possessed no response except that due to the intensity with which I read them, they became thus. In truth, during our years of study, there existed no significant books, nor were the libraries particularly adequate; yet, praise be to God, at present Shahid Beheshti University possesses an excellent general library, and we, in the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of the University of Tehran, have created a specialized library that compensates for all those deficiencies.”

Now, within the specialized Hall of Criminal Sciences, it is as though a portion of the history and historical works of Iran is preserved. For this reason, the exclusive coin of the first and most comprehensive library of criminal sciences of Iran has been minted in the name of the University of Tehran.

A criminological hall beyond a library

The Faculty of Law and Political Sciences of the University of Tehran, as one of the most ancient institutions of higher education in the country — established decades prior to the University of Tehran itself, the “mother university of Iran” — lacked this specialized library; the Information Hall and Library of Criminal Sciences, which was inaugurated less than a month ago (on November 3, 2024) in the presence of eminent professors of Iran’s criminological sciences, and will indubitably constitute a momentous step toward the advancement and dissemination of criminal law, criminology, and the stature of the Iranian legal and judicial system.

We inquire of him what factor, or indeed what factors, fortified the conception of establishing this library, and the present condition of society forms the most consequential segment of his response: “I am persuaded that one of the voids that presently exists in the educational system of our country — and likewise one of the causes of our failure in confronting the phenomenon of crimes, social harms, and economic offenses — is the absence of an autonomous educational and research institution. In a dispersed manner, groups in each faculty are engaged in this endeavor, yet no coherent center exists for this crucial matter, whereas in major nations of the world, university-based and research-based criminological centers exist that analyze the phenomenon of crimes and social harms. By this very rationale, the first step was undertaken so that the path toward eliminating this deficiency might be rendered traversable.”

Through the efforts of Dr. Abbas Shiri several years ago, apart from the principal field of Criminal Law and Criminology, the discipline of Juvenile and Adolescent Criminal Law (for which we likewise lacked specialized personnel) was established at the master’s level in this faculty, and until now, it has admitted seven or eight series of students. As he himself states, he has also prepared the doctoral curriculum for Juvenile and Adolescent Criminal Law because now, after these years and having attained intellectual profundity with respect to scientific substance, the university may initiate the doctoral level of this discipline as well.

He has likewise formulated a curriculum for another discipline entitled “Criminology,” its final stages concluded, and it stands on the threshold of promulgation by the Ministry of Science, Research, and Technology. Moreover, the development of other modern disciplines in the domain of criminological sciences — such as an independent discipline under the title of Criminology, International Criminal Law, and Criminal Justice — and the admission of students at the master’s level in these disciplines have been placed upon the agenda, and he hopes that beginning the semester after the next (September 2026), applicants to these fields will also be admitted.

A Step toward defending rights of Iranians in world

What appears significant amid the programmatic endeavors of Dr. Abbas Shiri is his effort to create a new academic discipline under the title “International Criminal Law.” The recent imposed 12-day war constitutes the nearest and most palpable circumstance elucidating this exigency. He likewise affirms this crucial matter and adds, “In this very 12-day war, we became cognizant of the importance of the existence of this academic discipline; the Leader likewise indicated that negligence has occurred in the legal domain, and this itself enabled us, with greater audacity and fortitude, to articulate that in the realm of international criminal law, we have exhibited considerable negligence, and we have not properly defended the rights of our country and our people (from the criminal-law perspective) in international forums, and we have not been able to utilize the capacities that exist in international institutions such as the International Criminal Court (ICC) or the International Court of Justice (ICJ) at The Hague, and so forth.”

Revisiting past to construct future

Adjacent to this library, an independent room containing several computers links students to the great libraries of the world. The digital segment of this hall has furnished access to thousands of volumes of books, articles, academic periodicals, and specialized collections. In this separate section, students become connected to an immense repository of digital resources. Internet speed and accessibility are in the process of enhancement, and the objective is that they may, without restriction and without onerous costs, gain access to global resources. Within the past few days, even the country-wide ban on accessing YouTube has been lifted at this university because the officials believe that YouTube constitutes a scientific dissemination platform rather than a moral impediment.

Imprint of history upon library shelves

In the brief interval since the library’s inauguration, the positive reception has been so overwhelming that the deans of Shiraz and Yazd universities have expressed their willingness to emulate this scholarly resource. During Dr. Shiri’s recent visits to these institutions, arrangements have been made to dedicate spaces specifically for specialized halls of criminology, with the provision of books entrusted to Dr. Shiri. He, who harbors aspirations to establish similar specialized halls in several of the country’s premier universities, has revealed that nearly 6,000 volumes exceeding the faculty’s immediate requirements are at his disposal; these books are intended for universities establishing specialized criminology libraries. Since they are donations and do not constitute university property, there exists no impediment to this allocation.

The Criminology Library of the University of Tehran is not merely a collection of books; it is a reflection of a history to be celebrated and a future to be meticulously constructed. It represents an endeavor to bridge the illustrious legacy of legal order in Iran with the complex exigencies of the contemporary era. Here is a locus where history is perused to script the future. Within this assemblage lie volumes of unparalleled historical and intellectual value.

One of the most striking aspects of this hall is the linguistic and chronological diversity of its holdings. These texts range from the earliest codifications of Iran’s criminal laws, dating to 1929, to works documenting the Iranian government’s accession to the Geneva Protocol in the same year. Substantial tomes in French testify to the presence of professors proficient in that language at the university, evincing that Iranian legal scholarship breathed through the Francophone intellectual milieu for decades. Complementing these are collections of Islamic jurisprudence in Arabic, bearing witness to the longstanding symbiosis between Iranian law and Sharia. In response to my inquiry regarding this remarkable linguistic diversity and the profusion of French volumes, Dr. Abbas Shiri elucidates, “In the past, the majority of the faculty in law and criminology, such as the late Dr. Katouzian, the late Dr. Mohammad Jafar Jafari Langaroudi, the late Seyed Hassan Emami, and many others, were either graduates of French institutions or proficient in French. Furthermore, a portion of these French texts was donated by Dr. Najafi, who was likewise proficient in the language.”

A number of the thousands of volumes housed within this library are unique, meaning they will never be reprinted; many are donations from eminent scholars and constitute a segment of Iran’s academic identity. Dr. Shiri observes: “These books, published over 80 years ago, I collected to demonstrate that Iran has possessed a legislative system for over a century, whereas many other nations’ histories of sovereignty extend only 40, 50, or 60 years, or in the case of the United States, at most 250 years. Yet we, 115 years ago, had a constitutional system; a parliament existed, bicameral governance was operational, and laws over a century old were codified.”

Naturally, many of these works remain current and indispensable for contemporary research. Thousands more will soon be added to these shelves, ensuring that the library’s holdings will reach no fewer than 10,000 volumes. The older theses housed here, however, constitute a remarkable universe unto themselves. As Dr. Shiri leafs through each, he appears a time traveler; for a fleeting moment, his imagination soars back to the 1340s and 1350s. Each thesis invites detailed commentary, and he responds with meticulous patience to every inquiry. These theses, some 60 to 80 years old, form a vital component of the library’s treasures. Dr. Shiri describes them as a “journey through time”: “While these theses may no longer be scientifically current, they are historical. They reveal the preoccupations of our professors half a century ago. The narrative is such that many scholars, upon discovering this library and its resources, approached me, offering access to theses in criminology defended over the decades by their predecessors. They inquired whether these would be of use to me, and I, believing a portion of our history is embedded within these pages, welcomed these proposals. Naturally, the content may have aged — such as research on theft conducted 50 years ago, which may no longer be citable — but it remains part of our history. The day foreign scholars visit this university, they will witness the field research undertaken by Iran’s eminent professors over more than half a century of academic activity within a lawful nation.”

I inquire about the unveiling of the Cyrus Cylinder at UNESCO and the connection he perceives between his most recent initiative and Iran’s civilizational heritage. With pride, he invokes Iran’s legislative history, emphasizing: “By reference to the advanced laws of the Sassanian era and the edicts of Sassanian and Achaemenid kings — such as prohibitions on polluting water, felling trees, or harming animals — I assert that Iran’s historical depth far exceeds the oft-repeated 2,500-year narrative. Everything that modern humanity esteems, we practiced thousands of years ago. Hence, it is erroneous to claim that Iran possesses a 2,500-year heritage; in reality, our legacy spans seven millennia. We take pride in the laws and decrees that, when Cyrus entered the lands he conquered, he acknowledged and decreed that every individual in those territories is free to adhere to their religion, language, and vocation. I regard this land as more illustrious than commonly perceived; we possess unique characteristics: we have never practiced idolatry. We are the only people who have always been monotheistic and God-fearing. Our society has upheld monogamy. We have never had slavery in Iran, whereas a country like the United States abolished slavery only in 1955 and commemorates individuals such as the martyred Abraham Lincoln for that act.”

Birth of Iran’s first law museum

In the neglected corners of the faculty courtyard, precious books and theses were heaped, destined for the trash. The value of these works could only be discerned by one enamored with their nation’s history, capable of salvaging them from academic refuse and presenting them within the glass display cases of the first Law Museum of the faculty.

Abbas Shiri’s profound attachment to Iran and its past has rendered him a skilled connoisseur of value, reviving the significance and quality of materials that many consider historical waste. He has restored rare and invaluable theses, defended decades ago within this very faculty at the doctoral level, believing that, had these works existed elsewhere, they would have commanded millions of dollars. With his characteristic tone, he regrets that items such as a cigarette stub once smoked by Queen Elizabeth or her last slipper are preserved for display, while a scholarly work over 60 years old was nearly lost to university waste. Fortunately, Dr. Shiri intervened in time and has so far organized nearly 30 percent of these works, dedicating polished glass tables to their exhibition. His intention is to restore every remaining volume in a similar fashion, granting enthusiasts of this valuable historical heritage the honor of viewing them.

I ask him whence this spirit and motivation arise. With calm pride, he replies: “Perhaps contemporary society may not appreciate it, but I am a traditionalist, and the history of Iran and the history of law are paramount to me.”

As he speaks proudly of Iran’s ancient history, he stands beside the first glass table of the Law Museum, presenting the voluminous thesis of Jahangir Amuzegar, penned in 1940.

This museum was established with the financial support of Dr. Abbas Mosallanejad and shaped by Dr. Abbas Shiri, wherein one of the most poignant yet luminous narratives has taken form. Several glass vitrines are arranged together to ensure that a portion of Iran’s scientific history is preserved.

From a distance, he follows the second glass vitrine. His eyes gleam with exhilaration. He quickens his pace and gestures to the first edition of the Law Faculty Library’s ledger from 1934, an index recorded in French. Emphasizing its meticulous detail, he remarks: “Observe! Written in French and in a seamless style. Our library staff in 1934 were so proficient in French that they recorded the information with remarkable precision and clarity.”

Perusing Iran’s past is akin to glimpsing the future. Dr. Abbas Shiri draws inspiration from this illustrious past, tirelessly striving to reveal the civilized visage of Iran. This valuable collection also houses approximately 150 to 200 volumes of Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh’s works, signed by him and donated to the university, placed in a dedicated section.

Across the museum, the thesis of one of Iran’s most distinguished constitutional law professors, Dr. Seyed Abolfazl Ghazi Shariatpanahi, is displayed with utmost respect. After receiving his Federal Doctorate in Public Law from a French university and a certificate from the French National School of Administration, he returned to Iran and, in 1970, was officially appointed associate professor at the University of Tehran Law Faculty, passing away in the 1990s due to cancer.

Along the display cases are works by Dr. Saadzadeh Afshar, writings of the late Iraj Afshar — the former head of the Central Library of the University of Tehran who had also bequeathed endowments to the university — theses by Dr. Mo’tameni Tabatabai on Iranian constitutional and administrative law, Dr. Fereydoun Adamiyat’s 1942 thesis, the late Dr. Langaroudi’s thesis under the guidance of Professor Mahmoud Shahabi, and finally, the thesis of the late Martyr Beheshti, who was himself a student at this faculty.

To properly organize the remaining invaluable and recently restored theses, at least 30 additional glass vitrines are required, so that, like the thesis of the late Dr. Nasser Katouzian — the father of Iranian legal science, defended in 1952 under the supervision of the late Ayatollah Sanglaji — they may embellish this museum.

Here, through scholarly diligence and integrity, a portion of Iran’s forgotten scientific heritage has been revived; a treasury that, if preserved, will present future generations with a clearer and more precise depiction of the history of Iranian law.

Prospect of future

According to the statements of Dr. Shiri, the possibility of benefiting from this novel environment is not restricted solely to students of the University of Tehran; practitioners in the criminological domain outside the University of Tehran may likewise utilize the resources of this hall and library. Yet considering that criminological sciences constitute a branch of the humanities, social sciences, and psychology — and that as we proceed further, the configuration of crimes in the country transforms due to cyber offenses — one must observe whether this primary academic resource will provide substantive material for the extensive spectrum of contemporary social harms that generally elude temporal constraints.

Dr. Shiri identifies the reason for dividing the criminological library into two segments, physical and digital, in these very modern offenses and asserts: “The reality is that paper remains behind the pace of transformations. In any case, transformations occur and research is conducted, but before it can be transferred onto paper, many years may elapse. The digital information hall, which is connected through computers to reputable libraries of the world, fulfills precisely this necessity. Students and researchers thus possess access to the most current global information, meaning that if an event transpires today, on this very day — through the virtual domain — they will obtain access to its manifold dimensions.”

He provides an elucidation for greater clarity and offers a tangible and delineated instance by referring to the homicide of the late Amirhossein Khaleqi, and to occurrences that arise in everyday life and in a continuous manner, constituting in some sense the contemporary subjects of criminological sciences — similar to matters raised in cases concerning figures such as Kolsoum Akbari, Tataloo, Elaheh Hosseinnezhad, Pejman Jamshidi, or even offenses pertaining to artificial intelligence. Irrespective of any adjudicative perspective on these cases, these cases are posited as matters that engage students, researchers, and the public. If they desire to compose a thesis or article concerning these hot-topic subjects, before the written information reaches the library, more than a year may pass, whereas through this digital information environment, one may attain novel and scientific analyses — or even peruse analyses produced by professors — and consequently, in the near future, conceive substantive theses centered upon these very subjects.

On this basis, I ask Dr. Shiri to also touch upon whether one can reasonably expect that this nascent library might, one day, serve as an authoritative reference for the judicial bodies of the nation and a key to unraveling contemporary crimes. His response, imbued with palpable enthusiasm, is even more compelling: “We have prepared a series of memoranda of understanding, some of which have been signed with the Judiciary, the Ministry of Interior, the Presidency, and the Police as one of the parties, while several others are on the verge of ratification.”