China’s middle corridor(s), east-west connectivity

By Ali Oskrouchi and Zenel Garcia

Scholars

The shifting geopolitical landscape of the 2020s has profoundly reshaped global trade corridors, particularly China’s overland routes to Europe. The outbreak of the Russia-Ukraine war and the United States’ turn toward economic nationalism, marked by escalating tariffs and strategic decoupling, have accelerated China’s push to diversify its freight pathways beyond maritime and Russian-dominated routes. These developments have made overland rail infrastructure a central pillar of Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), not only for trade facilitation but also for geopolitical resilience.

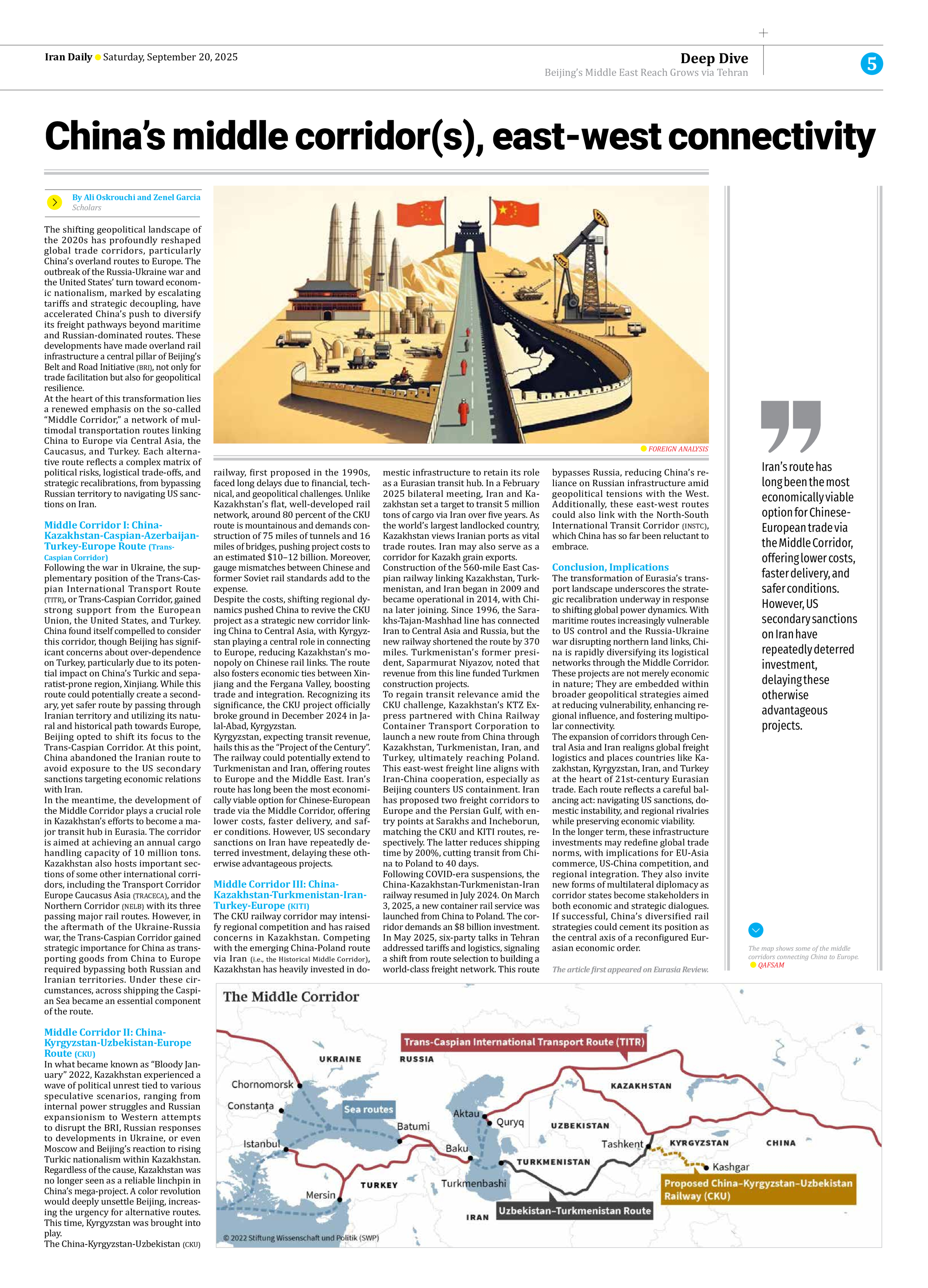

At the heart of this transformation lies a renewed emphasis on the so-called “Middle Corridor,” a network of multimodal transportation routes linking China to Europe via Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Turkey. Each alternative route reflects a complex matrix of political risks, logistical trade-offs, and strategic recalibrations, from bypassing Russian territory to navigating US sanctions on Iran.

Middle Corridor I: China-Kazakhstan-Caspian-Azerbaijan-Turkey-Europe Route (Trans-Caspian Corridor)

Following the war in Ukraine, the supplementary position of the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (TITR), or Trans-Caspian Corridor, gained strong support from the European Union, the United States, and Turkey. China found itself compelled to consider this corridor, though Beijing has significant concerns about over-dependence on Turkey, particularly due to its potential impact on China’s Turkic and separatist-prone region, Xinjiang. While this route could potentially create a secondary, yet safer route by passing through Iranian territory and utilizing its natural and historical path towards Europe, Beijing opted to shift its focus to the Trans-Caspian Corridor. At this point, China abandoned the Iranian route to avoid exposure to the US secondary sanctions targeting economic relations with Iran.

In the meantime, the development of the Middle Corridor plays a crucial role in Kazakhstan’s efforts to become a major transit hub in Eurasia. The corridor is aimed at achieving an annual cargo handling capacity of 10 million tons. Kazakhstan also hosts important sections of some other international corridors, including the Transport Corridor Europe Caucasus Asia (TRACECA), and the Northern Corridor (NELB) with its three passing major rail routes. However, in the aftermath of the Ukraine-Russia war, the Trans-Caspian Corridor gained strategic importance for China as transporting goods from China to Europe required bypassing both Russian and Iranian territories. Under these circumstances, across shipping the Caspian Sea became an essential component of the route.

Middle Corridor II: China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan-Europe Route (CKU)

In what became known as “Bloody January” 2022, Kazakhstan experienced a wave of political unrest tied to various speculative scenarios, ranging from internal power struggles and Russian expansionism to Western attempts to disrupt the BRI, Russian responses to developments in Ukraine, or even Moscow and Beijing’s reaction to rising Turkic nationalism within Kazakhstan. Regardless of the cause, Kazakhstan was no longer seen as a reliable linchpin in China’s mega-project. A color revolution would deeply unsettle Beijing, increasing the urgency for alternative routes. This time, Kyrgyzstan was brought into play.

The China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan (CKU) railway, first proposed in the 1990s, faced long delays due to financial, technical, and geopolitical challenges. Unlike Kazakhstan’s flat, well-developed rail network, around 80 percent of the CKU route is mountainous and demands construction of 75 miles of tunnels and 16 miles of bridges, pushing project costs to an estimated $10–12 billion. Moreover, gauge mismatches between Chinese and former Soviet rail standards add to the expense.

Despite the costs, shifting regional dynamics pushed China to revive the CKU project as a strategic new corridor linking China to Central Asia, with Kyrgyzstan playing a central role in connecting to Europe, reducing Kazakhstan’s monopoly on Chinese rail links. The route also fosters economic ties between Xinjiang and the Fergana Valley, boosting trade and integration. Recognizing its significance, the CKU project officially broke ground in December 2024 in Jalal-Abad, Kyrgyzstan.

Kyrgyzstan, expecting transit revenue, hails this as the “Project of the Century”. The railway could potentially extend to Turkmenistan and Iran, offering routes to Europe and the Middle East. Iran’s route has long been the most economically viable option for Chinese-European trade via the Middle Corridor, offering lower costs, faster delivery, and safer conditions. However, US secondary sanctions on Iran have repeatedly deterred investment, delaying these otherwise advantageous projects.

Middle Corridor III: China-Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran-Turkey-Europe (KITI)

The CKU railway corridor may intensify regional competition and has raised concerns in Kazakhstan. Competing with the emerging China-Poland route via Iran (i.e., the Historical Middle Corridor), Kazakhstan has heavily invested in domestic infrastructure to retain its role as a Eurasian transit hub. In a February 2025 bilateral meeting, Iran and Kazakhstan set a target to transit 5 million tons of cargo via Iran over five years. As the world’s largest landlocked country, Kazakhstan views Iranian ports as vital trade routes. Iran may also serve as a corridor for Kazakh grain exports.

Construction of the 560-mile East Caspian railway linking Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, and Iran began in 2009 and became operational in 2014, with China later joining. Since 1996, the Sarakhs-Tajan-Mashhad line has connected Iran to Central Asia and Russia, but the new railway shortened the route by 370 miles. Turkmenistan’s former president, Saparmurat Niyazov, noted that revenue from this line funded Turkmen construction projects.

To regain transit relevance amid the CKU challenge, Kazakhstan’s KTZ Express partnered with China Railway Container Transport Corporation to launch a new route from China through Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Iran, and Turkey, ultimately reaching Poland. This east-west freight line aligns with Iran-China cooperation, especially as Beijing counters US containment. Iran has proposed two freight corridors to Europe and the Persian Gulf, with entry points at Sarakhs and Incheborun, matching the CKU and KITI routes, respectively. The latter reduces shipping time by 200%, cutting transit from China to Poland to 40 days.

Following COVID-era suspensions, the China-Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan-Iran railway resumed in July 2024. On March 3, 2025, a new container rail service was launched from China to Poland. The corridor demands an $8 billion investment. In May 2025, six-party talks in Tehran addressed tariffs and logistics, signaling a shift from route selection to building a world-class freight network. This route bypasses Russia, reducing China’s reliance on Russian infrastructure amid geopolitical tensions with the West. Additionally, these east-west routes could also link with the North-South International Transit Corridor (INSTC), which China has so far been reluctant to embrace.

Conclusion, Implications

The transformation of Eurasia’s transport landscape underscores the strategic recalibration underway in response to shifting global power dynamics. With maritime routes increasingly vulnerable to US control and the Russia-Ukraine war disrupting northern land links, China is rapidly diversifying its logistical networks through the Middle Corridor. These projects are not merely economic in nature; They are embedded within broader geopolitical strategies aimed at reducing vulnerability, enhancing regional influence, and fostering multipolar connectivity.

The expansion of corridors through Central Asia and Iran realigns global freight logistics and places countries like Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Iran, and Turkey at the heart of 21st-century Eurasian trade. Each route reflects a careful balancing act: navigating US sanctions, domestic instability, and regional rivalries while preserving economic viability.

In the longer term, these infrastructure investments may redefine global trade norms, with implications for EU-Asia commerce, US-China competition, and regional integration. They also invite new forms of multilateral diplomacy as corridor states become stakeholders in both economic and strategic dialogues. If successful, China’s diversified rail strategies could cement its position as the central axis of a reconfigured Eurasian economic order.

The article first appeared on Eurasia Review.