Untapped potential of historic houses in South Khorasan Province

The historic houses of South Khorasan Province hold substantial potential for tourism development; however, many of these structures face the threat of deterioration for various reasons, including a lack of sufficient maintenance funds, improper utilization, and weak recognition. Revitalizing these buildings could play a pivotal role in stimulating the region’s economy and fostering sustainable tourism.

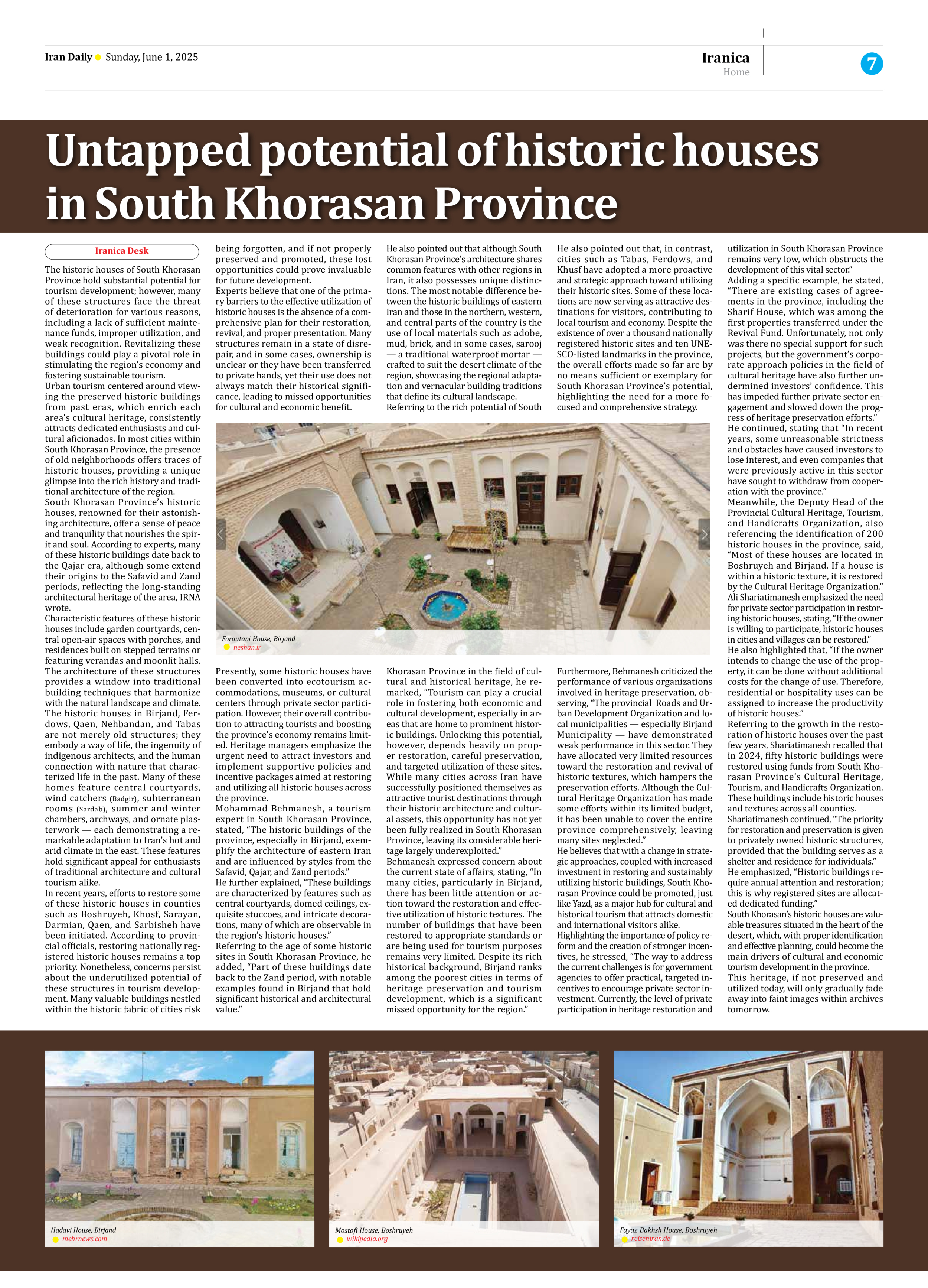

Urban tourism centered around viewing the preserved historic buildings from past eras, which enrich each area’s cultural heritage, consistently attracts dedicated enthusiasts and cultural aficionados. In most cities within South Khorasan Province, the presence of old neighborhoods offers traces of historic houses, providing a unique glimpse into the rich history and traditional architecture of the region.

South Khorasan Province’s historic houses, renowned for their astonishing architecture, offer a sense of peace and tranquility that nourishes the spirit and soul. According to experts, many of these historic buildings date back to the Qajar era, although some extend their origins to the Safavid and Zand periods, reflecting the long-standing architectural heritage of the area, IRNA wrote.

Characteristic features of these historic houses include garden courtyards, central open-air spaces with porches, and residences built on stepped terrains or featuring verandas and moonlit halls. The architecture of these structures provides a window into traditional building techniques that harmonize with the natural landscape and climate.

The historic houses in Birjand, Ferdows, Qaen, Nehbandan, and Tabas are not merely old structures; they embody a way of life, the ingenuity of indigenous architects, and the human connection with nature that characterized life in the past. Many of these homes feature central courtyards, wind catchers (Badgir), subterranean rooms (Sardab), summer and winter chambers, archways, and ornate plasterwork — each demonstrating a remarkable adaptation to Iran’s hot and arid climate in the east. These features hold significant appeal for enthusiasts of traditional architecture and cultural tourism alike.

In recent years, efforts to restore some of these historic houses in counties such as Boshruyeh, Khosf, Sarayan, Darmian, Qaen, and Sarbisheh have been initiated. According to provincial officials, restoring nationally registered historic houses remains a top priority. Nonetheless, concerns persist about the underutilized potential of these structures in tourism development. Many valuable buildings nestled within the historic fabric of cities risk being forgotten, and if not properly preserved and promoted, these lost opportunities could prove invaluable for future development.

Experts believe that one of the primary barriers to the effective utilization of historic houses is the absence of a comprehensive plan for their restoration, revival, and proper presentation. Many structures remain in a state of disrepair, and in some cases, ownership is unclear or they have been transferred to private hands, yet their use does not always match their historical significance, leading to missed opportunities for cultural and economic benefit.

Presently, some historic houses have been converted into ecotourism accommodations, museums, or cultural centers through private sector participation. However, their overall contribution to attracting tourists and boosting the province’s economy remains limited. Heritage managers emphasize the urgent need to attract investors and implement supportive policies and incentive packages aimed at restoring and utilizing all historic houses across the province.

Mohammad Behmanesh, a tourism expert in South Khorasan Province, stated, “The historic buildings of the province, especially in Birjand, exemplify the architecture of eastern Iran and are influenced by styles from the Safavid, Qajar, and Zand periods.”

He further explained, “These buildings are characterized by features such as central courtyards, domed ceilings, exquisite stuccoes, and intricate decorations, many of which are observable in the region’s historic houses.”

Referring to the age of some historic sites in South Khorasan Province, he added, “Part of these buildings date back to the Zand period, with notable examples found in Birjand that hold significant historical and architectural value.”

He also pointed out that although South Khorasan Province’s architecture shares common features with other regions in Iran, it also possesses unique distinctions. The most notable difference between the historic buildings of eastern Iran and those in the northern, western, and central parts of the country is the use of local materials such as adobe, mud, brick, and in some cases, sarooj — a traditional waterproof mortar — crafted to suit the desert climate of the region, showcasing the regional adaptation and vernacular building traditions that define its cultural landscape.

Referring to the rich potential of South Khorasan Province in the field of cultural and historical heritage, he remarked, “Tourism can play a crucial role in fostering both economic and cultural development, especially in areas that are home to prominent historic buildings. Unlocking this potential, however, depends heavily on proper restoration, careful preservation, and targeted utilization of these sites. While many cities across Iran have successfully positioned themselves as attractive tourist destinations through their historic architecture and cultural assets, this opportunity has not yet been fully realized in South Khorasan Province, leaving its considerable heritage largely underexploited.”

Behmanesh expressed concern about the current state of affairs, stating, “In many cities, particularly in Birjand, there has been little attention or action toward the restoration and effective utilization of historic textures. The number of buildings that have been restored to appropriate standards or are being used for tourism purposes remains very limited. Despite its rich historical background, Birjand ranks among the poorest cities in terms of heritage preservation and tourism development, which is a significant missed opportunity for the region.”

He also pointed out that, in contrast, cities such as Tabas, Ferdows, and Khusf have adopted a more proactive and strategic approach toward utilizing their historic sites. Some of these locations are now serving as attractive destinations for visitors, contributing to local tourism and economy. Despite the existence of over a thousand nationally registered historic sites and ten UNESCO-listed landmarks in the province, the overall efforts made so far are by no means sufficient or exemplary for South Khorasan Province’s potential, highlighting the need for a more focused and comprehensive strategy.

Furthermore, Behmanesh criticized the performance of various organizations involved in heritage preservation, observing, “The provincial Roads and Urban Development Organization and local municipalities — especially Birjand Municipality — have demonstrated weak performance in this sector. They have allocated very limited resources toward the restoration and revival of historic textures, which hampers the preservation efforts. Although the Cultural Heritage Organization has made some efforts within its limited budget, it has been unable to cover the entire province comprehensively, leaving many sites neglected.”

He believes that with a change in strategic approaches, coupled with increased investment in restoring and sustainably utilizing historic buildings, South Khorasan Province could be promoted, just like Yazd, as a major hub for cultural and historical tourism that attracts domestic and international visitors alike.

Highlighting the importance of policy reform and the creation of stronger incentives, he stressed, “The way to address the current challenges is for government agencies to offer practical, targeted incentives to encourage private sector investment. Currently, the level of private participation in heritage restoration and utilization in South Khorasan Province remains very low, which obstructs the development of this vital sector.”

Adding a specific example, he stated, “There are existing cases of agreements in the province, including the Sharif House, which was among the first properties transferred under the Revival Fund. Unfortunately, not only was there no special support for such projects, but the government’s corporate approach policies in the field of cultural heritage have also further undermined investors’ confidence. This has impeded further private sector engagement and slowed down the progress of heritage preservation efforts.”

He continued, stating that “In recent years, some unreasonable strictness and obstacles have caused investors to lose interest, and even companies that were previously active in this sector have sought to withdraw from cooperation with the province.”

Meanwhile, the Deputy Head of the Provincial Cultural Heritage, Tourism, and Handicrafts Organization, also referencing the identification of 200 historic houses in the province, said, “Most of these houses are located in Boshruyeh and Birjand. If a house is within a historic texture, it is restored by the Cultural Heritage Organization.”

Ali Shariatimanesh emphasized the need for private sector participation in restoring historic houses, stating, “If the owner is willing to participate, historic houses in cities and villages can be restored.”

He also highlighted that, “If the owner intends to change the use of the property, it can be done without additional costs for the change of use. Therefore, residential or hospitality uses can be assigned to increase the productivity of historic houses.”

Referring to the growth in the restoration of historic houses over the past few years, Shariatimanesh recalled that in 2024, fifty historic buildings were restored using funds from South Khorasan Province’s Cultural Heritage, Tourism, and Handicrafts Organization. These buildings include historic houses and textures across all counties.

Shariatimanesh continued, “The priority for restoration and preservation is given to privately owned historic structures, provided that the building serves as a shelter and residence for individuals.”

He emphasized, “Historic buildings require annual attention and restoration; this is why registered sites are allocated dedicated funding.”

South Khorasan’s historic houses are valuable treasures situated in the heart of the desert, which, with proper identification and effective planning, could become the main drivers of cultural and economic tourism development in the province.

This heritage, if not preserved and utilized today, will only gradually fade away into faint images within archives tomorrow.