From personal struggles to collective strength: ‘Self-Made’ in resistance

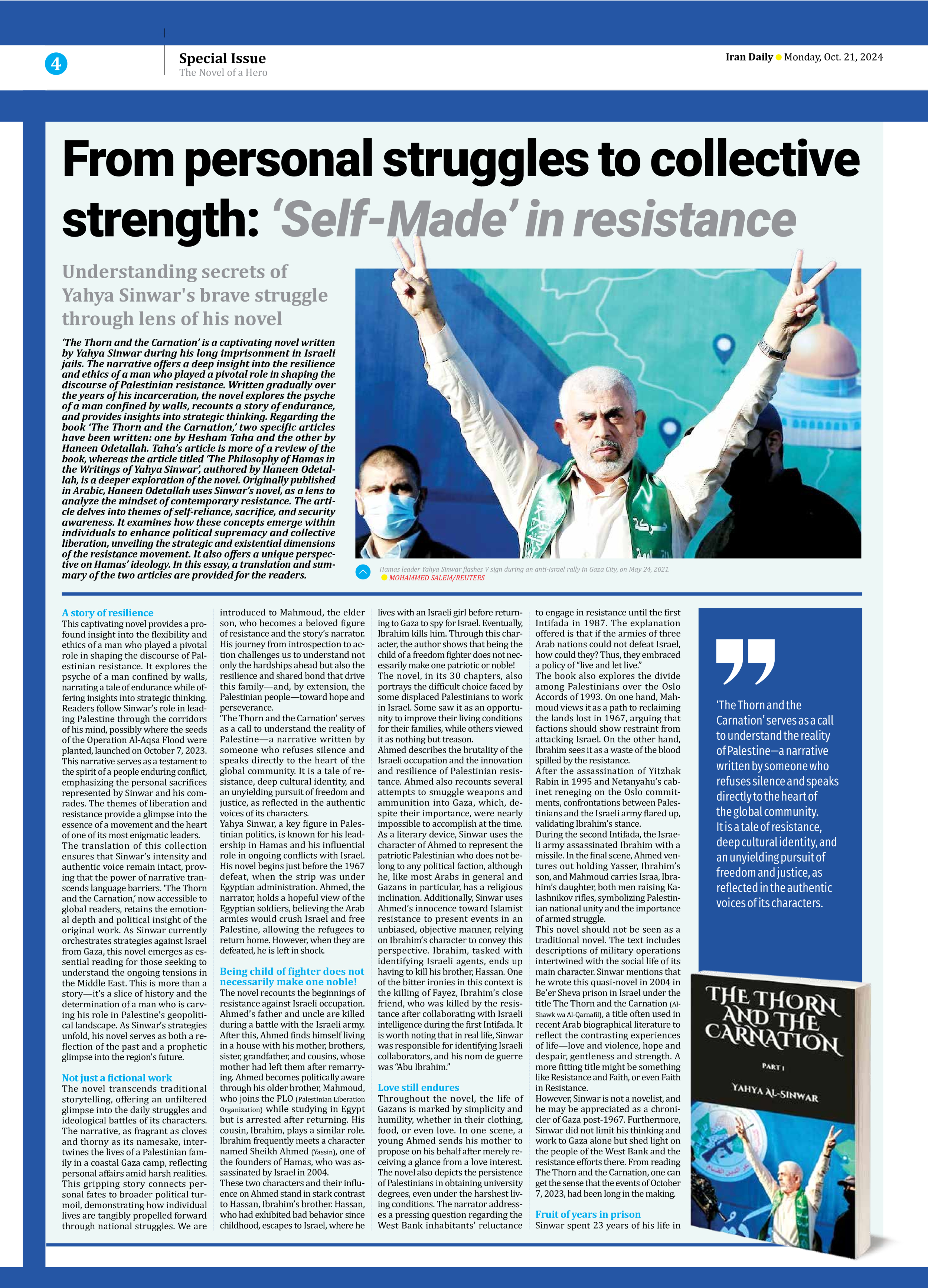

‘The Thorn and the Carnation’ is a captivating novel written by Yahya Sinwar during his long imprisonment in Israeli jails. The narrative offers a deep insight into the resilience and ethics of a man who played a pivotal role in shaping the discourse of Palestinian resistance. Written gradually over the years of his incarceration, the novel explores the psyche of a man confined by walls, recounts a story of endurance, and provides insights into strategic thinking. Regarding the book ‘The Thorn and the Carnation,’ two specific articles have been written: one by Hesham Taha and the other by Haneen Odetallah. Taha’s article is more of a review of the book, whereas the article titled ‘The Philosophy of Hamas in the Writings of Yahya Sinwar’, authored by Haneen Odetallah, is a deeper exploration of the novel. Originally published in Arabic, Haneen Odetallah uses Sinwar’s novel, as a lens to analyze the mindset of contemporary resistance. The article delves into themes of self-reliance, sacrifice, and security awareness. It examines how these concepts emerge within individuals to enhance political supremacy and collective liberation, unveiling the strategic and existential dimensions of the resistance movement. It also offers a unique perspective on Hamas’ ideology. In this essay, a translation and summary of the two articles are provided for the readers.

A story of resilience

This captivating novel provides a profound insight into the flexibility and ethics of a man who played a pivotal role in shaping the discourse of Palestinian resistance. It explores the psyche of a man confined by walls, narrating a tale of endurance while offering insights into strategic thinking. Readers follow Sinwar’s role in leading Palestine through the corridors of his mind, possibly where the seeds of the Operation Al-Aqsa Flood were planted, launched on October 7, 2023. This narrative serves as a testament to the spirit of a people enduring conflict, emphasizing the personal sacrifices represented by Sinwar and his comrades. The themes of liberation and resistance provide a glimpse into the essence of a movement and the heart of one of its most enigmatic leaders.

The translation of this collection ensures that Sinwar’s intensity and authentic voice remain intact, proving that the power of narrative transcends language barriers. ‘The Thorn and the Carnation,’ now accessible to global readers, retains the emotional depth and political insight of the original work. As Sinwar currently orchestrates strategies against Israel from Gaza, this novel emerges as essential reading for those seeking to understand the ongoing tensions in the Middle East. This is more than a story—it’s a slice of history and the determination of a man who is carving his role in Palestine’s geopolitical landscape. As Sinwar’s strategies unfold, his novel serves as both a reflection of the past and a prophetic glimpse into the region’s future.

Not just a fictional work

The novel transcends traditional storytelling, offering an unfiltered glimpse into the daily struggles and ideological battles of its characters. The narrative, as fragrant as cloves and thorny as its namesake, intertwines the lives of a Palestinian family in a coastal Gaza camp, reflecting personal affairs amid harsh realities. This gripping story connects personal fates to broader political turmoil, demonstrating how individual lives are tangibly propelled forward through national struggles. We are introduced to Mahmoud, the elder son, who becomes a beloved figure of resistance and the story’s narrator. His journey from introspection to action challenges us to understand not only the hardships ahead but also the resilience and shared bond that drive this family—and, by extension, the Palestinian people—toward hope and perseverance.

‘The Thorn and the Carnation’ serves as a call to understand the reality of Palestine—a narrative written by someone who refuses silence and speaks directly to the heart of the global community. It is a tale of resistance, deep cultural identity, and an unyielding pursuit of freedom and justice, as reflected in the authentic voices of its characters.

Yahya Sinwar, a key figure in Palestinian politics, is known for his leadership in Hamas and his influential role in ongoing conflicts with Israel. His novel begins just before the 1967 defeat, when the strip was under Egyptian administration. Ahmed, the narrator, holds a hopeful view of the Egyptian soldiers, believing the Arab armies would crush Israel and free Palestine, allowing the refugees to return home. However, when they are defeated, he is left in shock.

Being child of fighter does not necessarily make one noble!

The novel recounts the beginnings of resistance against Israeli occupation. Ahmed’s father and uncle are killed during a battle with the Israeli army. After this, Ahmed finds himself living in a house with his mother, brothers, sister, grandfather, and cousins, whose mother had left them after remarrying. Ahmed becomes politically aware through his older brother, Mahmoud, who joins the PLO (Palestinian Liberation Organization) while studying in Egypt but is arrested after returning. His cousin, Ibrahim, plays a similar role. Ibrahim frequently meets a character named Sheikh Ahmed (Yassin), one of the founders of Hamas, who was assassinated by Israel in 2004.

These two characters and their influence on Ahmed stand in stark contrast to Hassan, Ibrahim’s brother. Hassan, who had exhibited bad behavior since childhood, escapes to Israel, where he lives with an Israeli girl before returning to Gaza to spy for Israel. Eventually, Ibrahim kills him. Through this character, the author shows that being the child of a freedom fighter does not necessarily make one patriotic or noble!

The novel, in its 30 chapters, also portrays the difficult choice faced by some displaced Palestinians to work in Israel. Some saw it as an opportunity to improve their living conditions for their families, while others viewed it as nothing but treason.

Ahmed describes the brutality of the Israeli occupation and the innovation and resilience of Palestinian resistance. Ahmed also recounts several attempts to smuggle weapons and ammunition into Gaza, which, despite their importance, were nearly impossible to accomplish at the time. As a literary device, Sinwar uses the character of Ahmed to represent the patriotic Palestinian who does not belong to any political faction, although he, like most Arabs in general and Gazans in particular, has a religious inclination. Additionally, Sinwar uses Ahmed’s innocence toward Islamist resistance to present events in an unbiased, objective manner, relying on Ibrahim’s character to convey this perspective. Ibrahim, tasked with identifying Israeli agents, ends up having to kill his brother, Hassan. One of the bitter ironies in this context is the killing of Fayez, Ibrahim’s close friend, who was killed by the resistance after collaborating with Israeli intelligence during the first Intifada. It is worth noting that in real life, Sinwar was responsible for identifying Israeli collaborators, and his nom de guerre was “Abu Ibrahim.”

Love still endures

Throughout the novel, the life of Gazans is marked by simplicity and humility, whether in their clothing, food, or even love. In one scene, a young Ahmed sends his mother to propose on his behalf after merely receiving a glance from a love interest. The novel also depicts the persistence of Palestinians in obtaining university degrees, even under the harshest living conditions. The narrator addresses a pressing question regarding the West Bank inhabitants’ reluctance to engage in resistance until the first Intifada in 1987. The explanation offered is that if the armies of three Arab nations could not defeat Israel, how could they? Thus, they embraced a policy of “live and let live.”

The book also explores the divide among Palestinians over the Oslo Accords of 1993. On one hand, Mahmoud views it as a path to reclaiming the lands lost in 1967, arguing that factions should show restraint from attacking Israel. On the other hand, Ibrahim sees it as a waste of the blood spilled by the resistance.

After the assassination of Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 and Netanyahu’s cabinet reneging on the Oslo commitments, confrontations between Palestinians and the Israeli army flared up, validating Ibrahim’s stance.

During the second Intifada, the Israeli army assassinated Ibrahim with a missile. In the final scene, Ahmed ventures out holding Yasser, Ibrahim’s son, and Mahmoud carries Israa, Ibrahim’s daughter, both men raising Kalashnikov rifles, symbolizing Palestinian national unity and the importance of armed struggle.

This novel should not be seen as a traditional novel. The text includes descriptions of military operations intertwined with the social life of its main character. Sinwar mentions that he wrote this quasi-novel in 2004 in Be’er Sheva prison in Israel under the title The Thorn and the Carnation (Al-Shawk wa Al-Qarnafil), a title often used in recent Arab biographical literature to reflect the contrasting experiences of life—love and violence, hope and despair, gentleness and strength. A more fitting title might be something like Resistance and Faith, or even Faith in Resistance.

However, Sinwar is not a novelist, and he may be appreciated as a chronicler of Gaza post-1967. Furthermore, Sinwar did not limit his thinking and work to Gaza alone but shed light on the people of the West Bank and the resistance efforts there. From reading The Thorn and the Carnation, one can get the sense that the events of October 7, 2023, had been long in the making.

Fruit of years in prison

Sinwar spent 23 years of his life in prison, including four years in solitary confinement, yet none of these years were wasted. He learned Hebrew and absorbed everything he could about his enemy, even devising and executing a long-term intelligence plan from behind bars, which was considered highly complex at the time.

In 2004, after an intricate operation that involved significant efforts and recruiting numerous prisoners, Sinwar, still incarcerated at the time, published his novel titled The Thorn and the Carnation. The novel delves into the struggles of Palestinians during the historical periods between 1967 and the Al-Aqsa Intifada in the early 2000s, highlighting the rise of Islamic movements in Palestinian resistance—particularly the Islamic Resistance Movement, or Hamas.

The story expands to include relatives, neighbors, people from the camp, Gaza, the West Bank, and other occupied territories.

A medium for philosophy

The novel features fictional characters, yet all its events are real; the fictional aspect stems from turning these events into a narrative that meets the conditions of a novel, as the author mentions in the introduction. The author’s choice to document this critical stage in the history of armed resistance and present it creatively as a novel demonstrates that this effort goes far beyond merely recounting history and its events. It is not just a reflection of past events; it is a deep exploration of the philosophical and moral forces that shape historical movements. The characters in historical novels engage with philosophical struggles within the context of their times. In other words, it serves as a tool to understand the complex relationship between personal beliefs and the broader scope of history. Sinwar steps beyond the confines of traditional historiography to address the dramatic struggles in history, allowing him to explore their philosophical dimensions—particularly the impact of beliefs on history. This enables him to formulate a philosophy for the Islamic Resistance Movement.

Story of a boy from a

refugee camp

The story is narrated from the perspective of Ahmed, a boy from a refugee camp, who opens his eyes for the first time to a harsh and unforgiving world: the camp, the war, and the disappearance of his father, a resistance fighter, without a trace. Ahmed observes the camp society, its culture, and his mother’s concern for others’ honor and reputation—especially when her daughters are involved—and her strictness in this matter. In contrast, Ahmed enjoys accompanying his grandfather to prayer and social gatherings at the camp’s mosque.

Ahmed watches the political developments in the camp, Gaza, the West Bank, and across the occupied territories. He observes curfews, blockades, the relentless capture of resistance fighters, and collective punishment. He witnesses the normalization of the occupation, material stability, work permits, and leisure trips to the occupied territories, through which more people are coerced or forced to collaborate with the enemy. Ahmed sees Israeli prisons from which he, his relatives, and acquaintances were released and observes the power of determination and organization in changing reality. Most of all, Ahmed sees how the fight for freedom evolves in response to these conditions. Ahmed follows the rise of Hamas through the characters who developed, shaped, and embodied it.

The narrator plays the role of an involved observer. He doesn’t just watch; he accompanies Ibrahim in his work, studies, and struggle. This distance between Ibrahim and the movement he represents makes Ibrahim a figure whose greatness transcends the movement. Although Ibrahim does not engage directly with the occupying forces and only attains martyrdom at the end of the book, he knows his fate from the beginning and pursues it without attachment to his wife and children. Perhaps Ibrahim symbolizes a state that the narrator aspires for the political movement to cultivate in society or the ideal individual that the author hopes Hamas will create—a figure who achieves their goals by shaping their self-definition and establishing a political institution for Palestinians.

For the narrator, Ibrahim symbolizes the concept of the “self-made man,” which manifests in two instances. First, the narrator mentions that Ibrahim’s self-made nature grants him a sense of self-governance and purpose. He even became a professional builder, learning the trade from his friend, with whom he partnered, hired a laborer, and secured medium-sized construction contracts. In the second instance, the self-made individual is also a true leader.

Thus, being self-made is the foundation of a political leader capable of confronting the circumstances of occupation. “Every day, Ibrahim grew more transcendent and respected in my eyes; he was the one who grew up an orphan after his father was martyred when he was four years old, then was abandoned by his mother while still young, raised among us, and became a self-made man, and a true leader despite his young age and the difficult circumstances under occupation.”

“Übermensch” drives the resistance

In existential philosophy, Nietzsche introduces the idea of the “Übermensch” or the “superhuman”; an individual who embodies true freedom and has the power to shape their own destiny. According to Nietzsche, the transcendent individual is one who selects their goals and defines their values and principles without succumbing to societal pressures beyond their control. This concept invites individuals to embrace the “will to power,” an inner drive toward freedom and self-sovereignty. Thus, the Übermensch is an intellectual model of a person who breaks societal norms and creates new values.

In contrast, Sinwar’s transcendent individual is the self-made political figure; someone who chooses their goals in a way that contributes to their political liberation. They engage in shaping their identity and defining their values within the social and political framework that encompasses them. This process is not merely a personal quest for freedom but a political act that involves challenging and contributing to the formation of collective identity in a way that serves the freedom of the entire society.

The politically transcendent individual, through the self-made philosophy, is a model of the practical person who deals with inherited societal values—social, moral, and religious—as resources to strengthen their community’s drive for liberation and achieve political ascendance. They understand that their struggle against occupation is an existential battle and a war on the Palestinian “will to power”; that is, a war for their political self-governance. In this context, the self-made philosophy transcends individual autonomy and becomes a tool to influence and shape political discourse. The hardworking individual, committed to achieving their liberatory goal, harnesses all the efforts of others toward this objective. Regarding the Islamic Resistance Movement, it seeks through Islamic values to produce this transcendent individual or this elevated state within the Palestinian individual.

Awakening of Islamic consciousness

The novel begins in the winter of 1967, just before the Naksa (the result of the Six-Day War between Israel and the Arab nations), when Gaza was under Egyptian administration. Ahmed, then five years old, recounts one of his earliest memories—his interactions with Egyptian soldiers, whom he frequently visited. They played with him and gave him and his friends pistachio sweets. Then the war begins, and the soldiers shout at them to return, no longer giving them sweets.

“The occupation forces faced fierce resistance in one area and withdrew. Shortly after, a group of tanks and military jeeps appeared, flying Egyptian flags. The resistance fighters rejoiced, thinking reinforcements had arrived, and they emerged from their positions and trenches, firing into the air in celebration. They gathered to welcome the reinforcements, but when the convoy approached, heavy fire was opened on the fighters, killing them. Then, the Zionist flag was raised on those tanks and vehicles instead of the Egyptian flags.”

This scene marks an ideological turning point in the Palestinian struggle: the realization of the failure or inadequacy of Arab nationalism as a political current in instilling the necessary seriousness in individuals toward the Palestinian national cause, especially in the face of increasing challenges.

The philosophy of the self-made individual carries with it the condition of seriousness and commitment in pursuing one’s goals: “Self-made individuals view their goals with respect and conviction and approach their achievement with the utmost seriousness. Without compromise, they are simply committed to doing what it takes to achieve them.” Here, the “extraordinary connection between religion and nationalism” achieves this seriousness through the obligation of jihad or holy war, imbuing the national cause with sanctity and planting in the individual the strict seriousness necessary to achieve it, as the narrator states: “So that the battle takes its true dimensions and meets the required standards.”

When the self-made political individual surveys the situation, they find the Islamic system among the last social systems that has remained steadfast in the face of sociocide—the destruction of society—committed by the occupation. They find, in the intertwining of political practice and faith, in the transfer of the Palestinian’s existence and purpose to Allah, a principle that the enemy cannot disintegrate. The self-made individual sees in historical Islamic sites stable political edifices against the occupation’s attempts to erode awareness and distort direction. Hence, we find Ibrahim referring to the battle as a “battle of civilization, history, and existence,” organizing a trip for the youth to learn about their hidden lands and sacred Islamic historical sites, with the most significant being Al-Aqsa Mosque. These sites embody the flourishing of Palestinian culture, sovereignty, and the shaping of their land’s destiny.

Here, the architecture of Al-Aqsa Mosque and the majestic Dome of the Rock stands in stark contrast to the architecture of the refugee camp, which represents the state of confinement for Palestinians. Therefore, Hamas places special emphasis on Al-Aqsa to highlight the sacred historical meanings that immortalize the Palestinian cause, such as the Night Journey of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), forming a point of connection between the land of Palestine and the heavens. Perhaps this is why the battle for the freedom of Palestinian prisoners has been named The Flood of Al-Aqsa—to emphasize that the freedom of Palestinians carries a divine significance, and their liberation is a purpose for which they were created.

‘Asceticism’ drives struggle through emotions

The novel pays special attention to the stage of “training and preparation” in the history of Hamas’s formation. One day, a sheikh named Ahmed walks by the youth and adolescents in the camp, who wander the streets and pass their time playing. He warns them against idle amusements and urges them to instead engage in prayer, worship, and contemplation, linking all of this to the future of Islam, whose flag, he says, must be raised in the land of Palestine. He then spends decades with them, instilling Islamic values that promote asceticism and the renunciation of worldly desires in favor of the hereafter, creating a generation “capable of sacrifice and selflessness.”

Perhaps the novel’s thesis is also about love—love, which in Islamic terms represents the strongest bond with oneself and “worldly life.” In this novel, it is shown how love, alongside asceticism, reinforces the meaning of existence in political action. The narrator says: “A sense of peace overwhelmed me... Is this love? (...) Later, I was content to watch her go to university from afar. I desired nothing more, not even a glance. It was enough for me to love, and for her to understand that well.” Thus, Ahmed is content with knowing love in his own world and postpones pursuing it until the time when he can propose to the woman “who grew up from childhood.” He doesn’t feel the need for love simply because it is something he has always heard about.

Ibrahim then clarifies to Ahmed that he too knew love but, seeing himself as part of the national struggle, decided not to pursue it. He said: “It becomes a whip that the occupiers lash across the backs of lovers. Ahmed, when they map out this sacred, honorable relationship, they force them to abandon their first love—Jerusalem. Does love still have a place in our lives?” Ibrahim explains how structured asceticism in Islamic philosophy is reflected in political life. It is this training that enables individuals to struggle at any time.

The novel is also referred to as The Thorn and the Clove in some accounts.