Challenges of Abbasi Caravanserai in modern Semnan

A cultural heritage researcher wrote a note about the fate of the Shah Abbasi Caravanserai in Semnan, which served as a prison for around 20 years. He lamented that numerous interventions in this structure have prevented it from being included on the comprehensive list of Iranian caravanserais eligible for world heritage status.

Hani Rastgaran noted that the city of Semnan currently comprises two distinct areas: old and new. Each section possesses its own unique values. The old part of the city is cohesive and densely built, while the new section is fragmented and dispersed, ISNA wrote.

In the old part of any city, specific elements reflect its identity, whereas the new areas tend to resemble each other more closely. Despite significant wear and tear, the old section still retains visual value in some areas, although it faces various challenges regarding habitation and transportation. In contrast, the new part of the city, despite its wide streets and modern urban facilities, lacks visual appeal. In Semnan, the new area has developed to the north, adjacent to the old area. The layout of the old city is characterized by specific neighborhoods, designed around pools that divided water for irrigation.

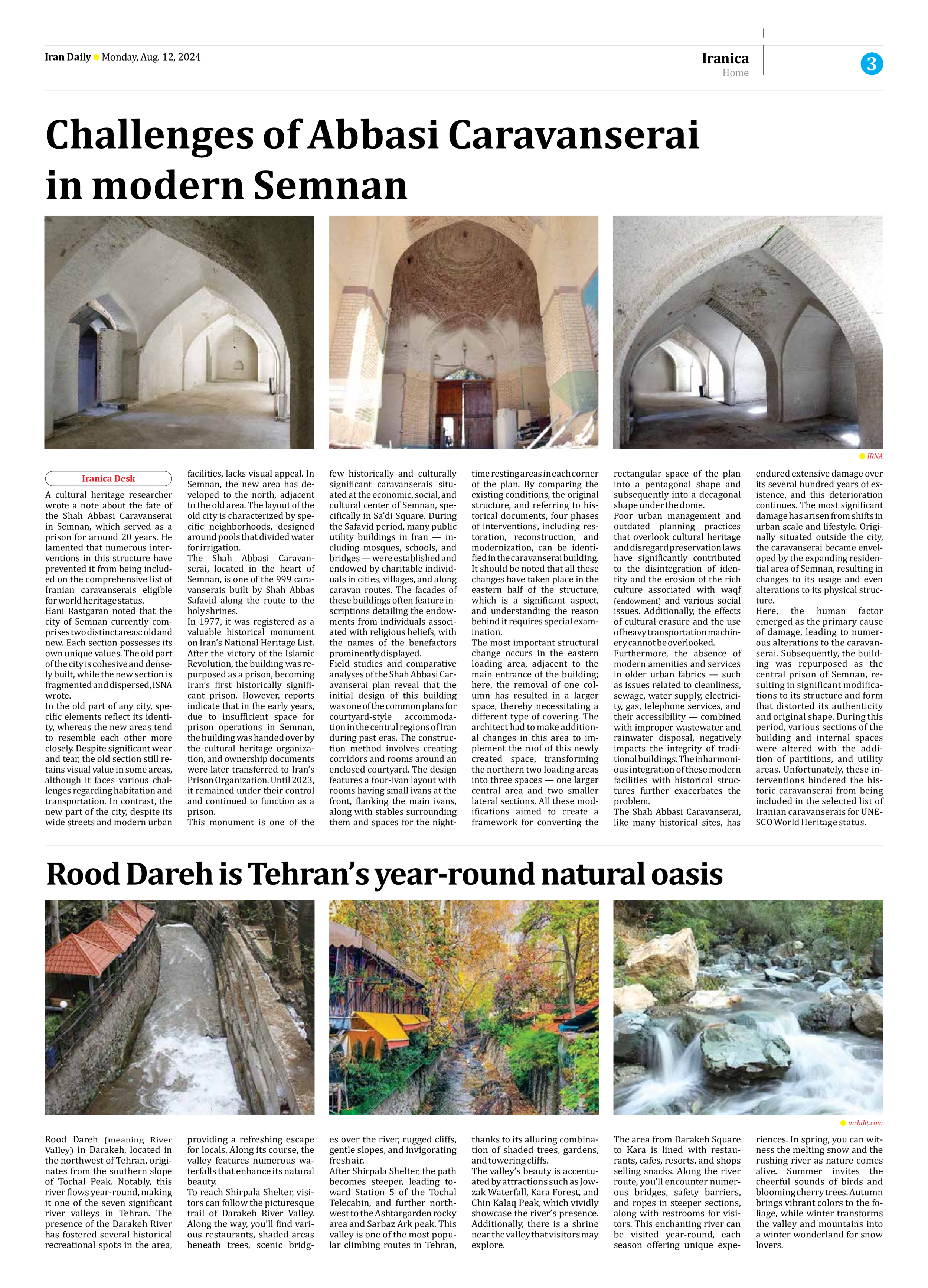

The Shah Abbasi Caravanserai, located in the heart of Semnan, is one of the 999 caravanserais built by Shah Abbas Safavid along the route to the holy shrines.

In 1977, it was registered as a valuable historical monument on Iran’s National Heritage List. After the victory of the Islamic Revolution, the building was repurposed as a prison, becoming Iran’s first historically significant prison. However, reports indicate that in the early years, due to insufficient space for prison operations in Semnan, the building was handed over by the cultural heritage organization, and ownership documents were later transferred to Iran’s Prison Organization. Until 2023, it remained under their control and continued to function as a prison.

This monument is one of the few historically and culturally significant caravanserais situated at the economic, social, and cultural center of Semnan, specifically in Sa’di Square. During the Safavid period, many public utility buildings in Iran — including mosques, schools, and bridges — were established and endowed by charitable individuals in cities, villages, and along caravan routes. The facades of these buildings often feature inscriptions detailing the endowments from individuals associated with religious beliefs, with the names of the benefactors prominently displayed.

Field studies and comparative analyses of the Shah Abbasi Caravanserai plan reveal that the initial design of this building was one of the common plans for courtyard-style accommodation in the central regions of Iran during past eras. The construction method involves creating corridors and rooms around an enclosed courtyard. The design features a four-ivan layout with rooms having small ivans at the front, flanking the main ivans, along with stables surrounding them and spaces for the nighttime resting areas in each corner of the plan. By comparing the existing conditions, the original structure, and referring to historical documents, four phases of interventions, including restoration, reconstruction, and modernization, can be identified in the caravanserai building.

It should be noted that all these changes have taken place in the eastern half of the structure, which is a significant aspect, and understanding the reason behind it requires special examination.

The most important structural change occurs in the eastern loading area, adjacent to the main entrance of the building; here, the removal of one column has resulted in a larger space, thereby necessitating a different type of covering. The architect had to make additional changes in this area to implement the roof of this newly created space, transforming the northern two loading areas into three spaces — one larger central area and two smaller lateral sections. All these modifications aimed to create a framework for converting the rectangular space of the plan into a pentagonal shape and subsequently into a decagonal shape under the dome.

Poor urban management and outdated planning practices that overlook cultural heritage and disregard preservation laws have significantly contributed to the disintegration of identity and the erosion of the rich culture associated with waqf (endowment) and various social issues. Additionally, the effects of cultural erasure and the use of heavy transportation machinery cannot be overlooked.

Furthermore, the absence of modern amenities and services in older urban fabrics — such as issues related to cleanliness, sewage, water supply, electricity, gas, telephone services, and their accessibility — combined with improper wastewater and rainwater disposal, negatively impacts the integrity of traditional buildings. The inharmonious integration of these modern facilities with historical structures further exacerbates the problem.

The Shah Abbasi Caravanserai, like many historical sites, has endured extensive damage over its several hundred years of existence, and this deterioration continues. The most significant damage has arisen from shifts in urban scale and lifestyle. Originally situated outside the city, the caravanserai became enveloped by the expanding residential area of Semnan, resulting in changes to its usage and even alterations to its physical structure.

Here, the human factor emerged as the primary cause of damage, leading to numerous alterations to the caravanserai. Subsequently, the building was repurposed as the central prison of Semnan, resulting in significant modifications to its structure and form that distorted its authenticity and original shape. During this period, various sections of the building and internal spaces were altered with the addition of partitions, and utility areas. Unfortunately, these interventions hindered the historic caravanserai from being included in the selected list of Iranian caravanserais for UNESCO World Heritage status.