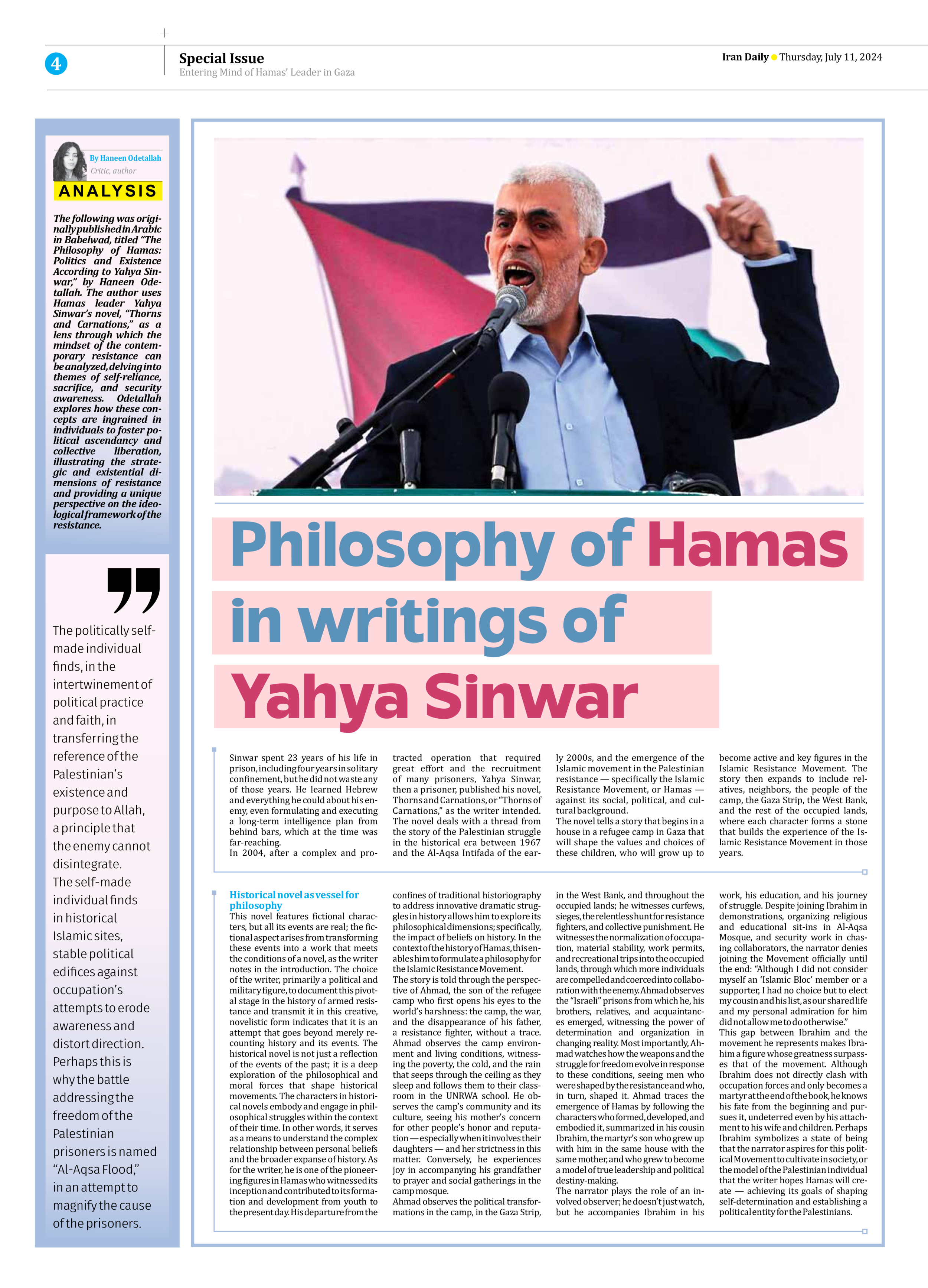

Philosophy of Hamas in writings of Yahya Sinwar

The following was originally published in Arabic in Babelwad, titled “The Philosophy of Hamas: Politics and Existence According to Yahya Sinwar,” by Haneen Odetallah. The author uses Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar’s novel, “Thorns and Carnations,” as a lens through which the mindset of the contemporary resistance can be analyzed, delving into themes of self-reliance, sacrifice, and security awareness. Odetallah explores how these concepts are ingrained in individuals to foster political ascendancy and collective liberation, illustrating the strategic and existential dimensions of resistance and providing a unique perspective on the ideological framework of the resistance.

By Haneen Odetallah

Critic, author

Sinwar spent 23 years of his life in prison, including four years in solitary confinement, but he did not waste any of those years. He learned Hebrew and everything he could about his enemy, even formulating and executing a long-term intelligence plan from behind bars, which at the time was far-reaching.

In 2004, after a complex and protracted operation that required great effort and the recruitment of many prisoners, Yahya Sinwar, then a prisoner, published his novel, Thorns and Carnations, or “Thorns of Carnations,” as the writer intended. The novel deals with a thread from the story of the Palestinian struggle in the historical era between 1967 and the Al-Aqsa Intifada of the early 2000s, and the emergence of the Islamic movement in the Palestinian resistance — specifically the Islamic Resistance Movement, or Hamas — against its social, political, and cultural background.

The novel tells a story that begins in a house in a refugee camp in Gaza that will shape the values and choices of these children, who will grow up to become active and key figures in the Islamic Resistance Movement. The story then expands to include relatives, neighbors, the people of the camp, the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, and the rest of the occupied lands, where each character forms a stone that builds the experience of the Islamic Resistance Movement in those years.

Historical novel as vessel for philosophy

This novel features fictional characters, but all its events are real; the fictional aspect arises from transforming these events into a work that meets the conditions of a novel, as the writer notes in the introduction. The choice of the writer, primarily a political and military figure, to document this pivotal stage in the history of armed resistance and transmit it in this creative, novelistic form indicates that it is an attempt that goes beyond merely recounting history and its events. The historical novel is not just a reflection of the events of the past; it is a deep exploration of the philosophical and moral forces that shape historical movements. The characters in historical novels embody and engage in philosophical struggles within the context of their time. In other words, it serves as a means to understand the complex relationship between personal beliefs and the broader expanse of history. As for the writer, he is one of the pioneering figures in Hamas who witnessed its inception and contributed to its formation and development from youth to the present day. His departure from the confines of traditional historiography to address innovative dramatic struggles in history allows him to explore its philosophical dimensions; specifically, the impact of beliefs on history. In the context of the history of Hamas, this enables him to formulate a philosophy for the Islamic Resistance Movement.

The story is told through the perspective of Ahmad, the son of the refugee camp who first opens his eyes to the world’s harshness: the camp, the war, and the disappearance of his father, a resistance fighter, without a trace. Ahmad observes the camp environment and living conditions, witnessing the poverty, the cold, and the rain that seeps through the ceiling as they sleep and follows them to their classroom in the UNRWA school. He observes the camp’s community and its culture, seeing his mother’s concern for other people’s honor and reputation — especially when it involves their daughters — and her strictness in this matter. Conversely, he experiences joy in accompanying his grandfather to prayer and social gatherings in the camp mosque.

Ahmad observes the political transformations in the camp, in the Gaza Strip, in the West Bank, and throughout the occupied lands; he witnesses curfews, sieges, the relentless hunt for resistance fighters, and collective punishment. He witnesses the normalization of occupation, material stability, work permits, and recreational trips into the occupied lands, through which more individuals are compelled and coerced into collaboration with the enemy. Ahmad observes the “Israeli” prisons from which he, his brothers, relatives, and acquaintances emerged, witnessing the power of determination and organization in changing reality. Most importantly, Ahmad watches how the weapons and the struggle for freedom evolve in response to these conditions, seeing men who were shaped by the resistance and who, in turn, shaped it. Ahmad traces the emergence of Hamas by following the characters who formed, developed, and embodied it, summarized in his cousin Ibrahim, the martyr’s son who grew up with him in the same house with the same mother, and who grew to become a model of true leadership and political destiny-making.

The narrator plays the role of an involved observer; he doesn’t just watch, but he accompanies Ibrahim in his work, his education, and his journey of struggle. Despite joining Ibrahim in demonstrations, organizing religious and educational sit-ins in Al-Aqsa Mosque, and security work in chasing collaborators, the narrator denies joining the Movement officially until the end: “Although I did not consider myself an ‘Islamic Bloc’ member or a supporter, I had no choice but to elect my cousin and his list, as our shared life and my personal admiration for him did not allow me to do otherwise.”

This gap between Ibrahim and the movement he represents makes Ibrahim a figure whose greatness surpasses that of the movement. Although Ibrahim does not directly clash with occupation forces and only becomes a martyr at the end of the book, he knows his fate from the beginning and pursues it, undeterred even by his attachment to his wife and children. Perhaps Ibrahim symbolizes a state of being that the narrator aspires for this political Movement to cultivate in society, or the model of the Palestinian individual that the writer hopes Hamas will create — achieving its goals of shaping self-determination and establishing a political entity for the Palestinians.

Self-made individual

Ibrahim’s transcendence, as perceived by the narrator, is linked to the concept of being “self-made,” which appears in two instances. In the first instance, the narrator notes that Ibrahim’s self-made nature has granted him a form of sovereignty over himself and a sense of purpose. “He even became a professional builder; he learned the trade from his friend, and they became partners, employing a worker to assist them, taking on medium-sized building contracts. It became clear that Ibrahim’s self-made nature was making a man out of him.”

Linguistically, the concept of being self-made refers to someone who has “achieved eminence by the virtue of their own character, not by the virtue of their ancestors”. The term has been commonly used to describe anyone “toiling, striving to develop themselves through their own efforts”. Thus, to be self-made can be considered philosophically as an existential practice where an individual finds the meaning of their existence and life by adhering to firm principles such as personal responsibility, autonomy, and intellectual freedom. These principles will elevate and develop the individual in pursuit of self-sovereignty and the shaping of their desired destiny.

In the second instance, the self-made individual is associated with the true leader; thus, being self-made is the foundation for a political leader capable of confronting the circumstances of occupation. “Every day, Ibrahim grew more transcendent and respected in my eyes; he was the one who grew up an orphan after his father was martyred when he was four years old, then was abandoned by his mother while still young, raised among us, and became a self-made man, and a true leader despite his young age and the difficult circumstances under occupation.”

When Ibrahim’s self-made nature merges with its political dimension, it makes him a leader; someone capable of developing not only himself but also his community and his people, elevating their collective condition. He carries them beyond, to overcome the difficult political circumstances towards freedom. For the narrator, Ibrahim embodies this model of the transcendent human being, who ascends and elevates themselves by finding the meaning of their existence in their commitment to the political role of uplifting their people. In other words, they ascend through a political practice philosophically founded on self-made principles.

Übermensch, self-made individual

In existential philosophy, Nietzsche introduces the idea of the “Übermensch,” an individual who has transcended and ascended to achieve true freedom embodied in the ability to shape their own destiny. According to Nietzsche, the transcendent individual is one who chooses their goals and selects their values, and principles without succumbing to any societal pressures beyond their control. This concept invites individuals to embrace what he calls the “Will to Power,” an inner drive for liberation and self-sovereignty. Thus, the Übermensch forms an intellectual model of a person who overcomes societal values and standards that hinder them and creates their own values.

In contrast, Sinwar’s transcendent individual is the politically self-made individual; one who chooses their goals in a way that contributes to their political liberation. Therefore, they engage in shaping their identity and defining their values within the social and political fabric that shelters them. This process is not merely a personal quest for freedom but a political act that involves challenging and contributing to the formation of collective identity in a way that serves the freedom of the entire community.

The politically transcendent individual, through the self-made philosophy, is a model of the practical person who deals with inherited societal values—social, moral, and religious—as resources to enhance their community’s drive for liberation and to achieve political ascendance. They understand that their struggle against occupation is an existential battle and a war on the Palestinian “will to power”; that is, a war on their drive to politically self-govern. In this context, self-made philosophy transcends individual self-determination and becomes a tool to influence and shape political discourse. The hard-working individual committed to achieving their liberatory goal will harness all the efforts of others for that purpose as much as they can. As for the Islamic Resistance Movement, it seeks through Islamic values to produce this transcendent individual, or this state of being in the Palestinian individual; so how do these values contribute to that?

“The house became filled with men and women, boys and girls from the same family, and memories flooded back of us as children gathered in a small room that was too big for us. Our modest family had grown into a small army over the years… I mentioned this jokingly; my mother quickly shouted, ‘Send blessings upon the Prophet,’ a gentle reminder to mind my words. Immediately, everyone chorused, ‘O Allah, bless our master Muhammad.’”

Islam, self-made individual

The novel begins in the winter of 1967, just before the Naksa, when Gaza was under the administration of Egypt. Ahmad, then five years old, recounts one of his earliest memories — his interactions with Egyptian soldiers whom he frequently visits. They would play with him and give him and his friends pistachio sweets. Then, the war breaks out, and the soldiers shout at them to go back, and they no longer get any sweets.

“The occupation forces had faced fierce resistance in one area and withdrew. Shortly after, a group of tanks and military jeeps appeared, flying Egyptian flags. The resistance fighters rejoiced, thinking help had arrived, and they emerged from their positions and trenches, firing into the air in celebration. They gathered to welcome the reinforcements, but when the convoy approached, heavy fire was opened on the fighters, killing them. Then, the Zionist flag was raised on those tanks and vehicles, instead of the Egyptian flags.”

This scene signals an ideological turning point in the Palestinian struggle: the realization of the failure of Arab nationalism, or its inadequacy as a political current in inducing the necessary seriousness in individuals towards the Palestinian national cause, especially in the face of the ever-increasing voracity of the occupation.

While the philosophy of the self-made individual encompasses a condition for elevation, which is seriousness and commitment to the pursuit, “self-made individuals look at their goals with respect and belief, and they take the matter of achieving them with utmost seriousness, without compromise. They are simply committed to what they must do to achieve that.” Here, the “extraordinary connection between religion and nationalism” achieves this seriousness through the obligation of jihad, or holy war, imbuing the national cause with sanctity and thus planting in the individual the strict seriousness necessary to achieve it, as the narrator states: “So that the battle takes its true dimension and meets the required standard.”

When the politically self-made individual looks around, they find the Islamic system among the last social systems that have remained steadfast among Palestinians in the face of societal annihilation, or sociocide, committed by the occupation. They find, in the intertwinement of political practice and faith, in transferring the reference of the Palestinian’s existence and purpose to Allah, a principle that the enemy cannot disintegrate. The self-made individual finds in historical Islamic sites, stable political edifices against occupation’s attempts to erode awareness and distort direction. Therefore, we find Ibrahim, who calls the battle “a battle of civilization, history, and existence,” organizing a trip for the youth to learn about their concealed lands and their sacred and historical Islamic sites, the foremost being al-Aqsa Mosque. These sites are where the flourishing of Palestinian culture, self-sovereignty, and the shaping of their land destiny are embodied.

Here, the architecture of al-Aqsa Mosque and the majestic Dome of the Rock stand in stark contrast to the architecture of the refugee camp, which embodies the state of confinement for Palestinians. Hence, Hamas places special emphasis on al-Aqsa for encapsulating the sacred historical meanings that immortalize the Palestinian cause, like al-Isra’ wa al-Mi’raj, or the Night Journey of Prophet Muhammad, forming a point of connection between the land of Palestine and the heavens. Perhaps this is why the battle addressing the freedom of the Palestinian prisoners is named “al-Aqsa Flood,” in an attempt to magnify the cause of the prisoners, emphasizing that the freedom of Palestinians is the meaning for which their Lord created them. Although Islam links the political struggle to Allah and the meaning of human existence, this connection goes beyond merely granting the struggle lofty meanings such as the afterlife and reward from Allah. So, how do these meanings practically manifest in individuals who practice a life centered around politics?

Asceticism

The novel pays special attention to the phase of “education and preparation” in the history of Hamas’s inception. One day, a Sheikh, also named Ahmad, passes by the young men and teenagers of the camp who are loitering in the streets and spending their time playing around. He warns them against useless amusement and urges them to engage in prayer, worship, and contemplation instead, “linking all of this to the future of Islam, whose banner must be raised in the land of Palestine.” The Sheikh then spends decades with them, instilling Islamic values that promote asceticism and renunciation of worldly desires in favor of the hereafter, creating a generation “capable of sacrifice and self-sacrifice”.

Perhaps the novel’s thesis on love, which represents the most intense connection to the self and the “mundane life” in Islamic terms, showcases how this asceticism enhances the meaning of existence in political practice. The narrator says, “It overwhelmed me with a feeling of comfort… Is this love? (…) I was later sufficed with watching her leave for university from afar; not aspiring for more than that, not even a glance. It was enough for me to love, and it was enough that she understood that well.” Thus, Ahmad is satisfied with knowing love in his world, postponing its attainment until the appropriate time when he can propose to her as he was “raised since his childhood”. He does not feel the need for love just because it is the “Love” that he has always heard about.

Ibrahim then clarifies to Ahmad that he, too, knew love, and because he considers himself part of the national struggle, he decided not to pursue it, stating that “it turns into a whip with which the occupation lashes the backs of those in love with one another. Ahmad, when this noble sacred relationship is used by collaborators as a pressure card on lovers, forcing them to abandon their first love, Al-Quds, is there still room for love and passion in our lives?” Ibrahim explains how systematic asceticism in Islamic philosophy reflects on political life; it is an upbringing that allows an individual to renounce desires at any time if they conflict with or endanger their national endeavor. It molds the individual such that the national endeavor becomes the central meaning of his life, his foremost desire, and the foundation upon which he constructs other aspects of his life.

The full article first appeared on Mondoweiss.