Copy in clipboard...

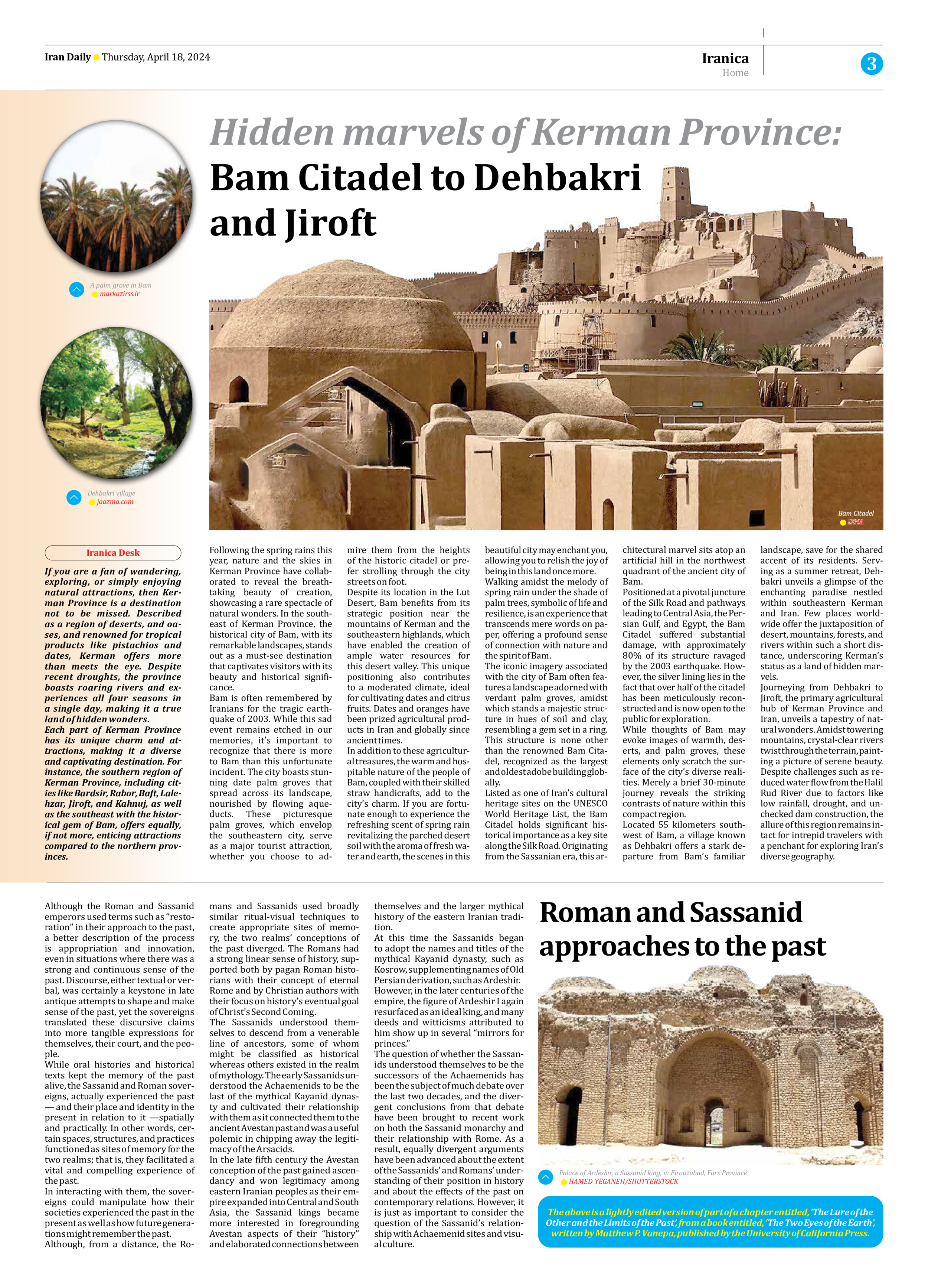

Roman and Sassanid approaches to the past

While oral histories and historical texts kept the memory of the past alive, the Sassanid and Roman sovereigns, actually experienced the past — and their place and identity in the present in relation to it —spatially and practically. In other words, certain spaces, structures, and practices functioned as sites of memory for the two realms; that is, they facilitated a vital and compelling experience of the past.

In interacting with them, the sovereigns could manipulate how their societies experienced the past in the present as well as how future generations might remember the past.

Although, from a distance, the Romans and Sassanids used broadly similar ritual-visual techniques to create appropriate sites of memory, the two realms’ conceptions of the past diverged. The Romans had a strong linear sense of history, supported both by pagan Roman historians with their concept of eternal Rome and by Christian authors with their focus on history’s eventual goal of Christ’s Second Coming.

The Sassanids understood themselves to descend from a venerable line of ancestors, some of whom might be classified as historical whereas others existed in the realm of mythology. The early Sassanids understood the Achaemenids to be the last of the mythical Kayanid dynasty and cultivated their relationship with them as it connected them to the ancient Avestan past and was a useful polemic in chipping away the legitimacy of the Arsacids.

In the late fifth century the Avestan conception of the past gained ascendancy and won legitimacy among eastern Iranian peoples as their empire expanded into Central and South Asia, the Sassanid kings became more interested in foregrounding Avestan aspects of their “history” and elaborated connections between themselves and the larger mythical history of the eastern Iranian tradition.

At this time the Sassanids began to adopt the names and titles of the mythical Kayanid dynasty, such as Kosrow, supplementing names of Old Persian derivation, such as Ardeshir.

However, in the later centuries of the empire, the figure of Ardeshir I again resurfaced as an ideal king, and many deeds and witticisms attributed to him show up in several “mirrors for princes.”

The question of whether the Sassanids understood themselves to be the successors of the Achaemenids has been the subject of much debate over the last two decades, and the divergent conclusions from that debate have been brought to recent work on both the Sassanid monarchy and their relationship with Rome. As a result, equally divergent arguments have been advanced about the extent of the Sassanids’ and Romans’ understanding of their position in history and about the effects of the past on contemporary relations. However, it is just as important to consider the question of the Sassanid’s relationship with Achaemenid sites and visual culture.