Influence of Islamic art and craftsmanship in 19th century Vienna

Broadly speaking, the 19th century witnessed a slow economic rise in Europe. Much of the rest of the world, including several Islamic countries, were to a large part integrated into the colonial empires of European powers. The Austro-Hungarian Empire possessed no overseas colonies and showed no obvious interest in acquiring any. The empire’s status meant that it was a comparatively neutral trading partner for Persia, which held a relationship with the Habsburg Dynasty that dated back to the 16th century.

At that time, the Habsburgs tried to forge alliances with the Safavid Empire against their common enemy, the Ottomans. From around 1600 onwards embassies were exchanged between Vienna and Persia and friendly relations continued between the Habsburgs and the later Persian dynasties.

Although politically more and more marginalised and economically weak, skilled craftsmanship of the Islamic world continued to be appreciated in Europe. During the Biedermeier period, for instance, there was a fascination on behalf of female consumers with cashmere shawls from north India, which were then produced in Europe imitating Indian models. The Museum für angewandte Kunst includes several valuable pieces that derive from 19th-century Viennese producers. Not only were objects from the wider Persian world admired in Vienna, but they were occasionally also copied there, just like the Mamluk glass vessels by the celebrated Viennese glass manufacture J. & L. Lobmeyr.

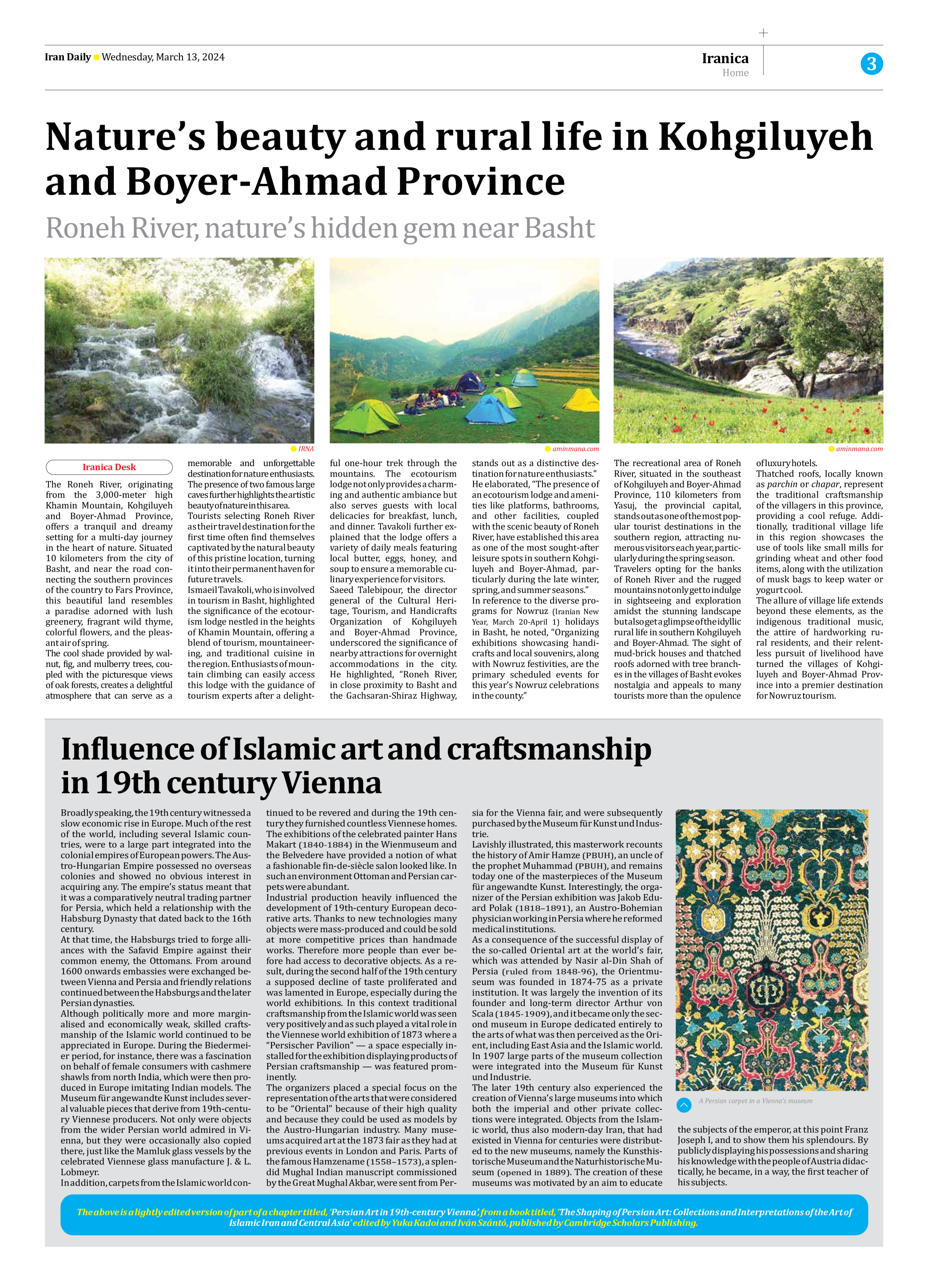

In addition, carpets from the Islamic world continued to be revered and during the 19th century they furnished countless Viennese homes. The exhibitions of the celebrated painter Hans Makart (1840-1884) in the Wienmuseum and the Belvedere have provided a notion of what a fashionable fin-de-siècle salon looked like. In such an environment Ottoman and Persian carpets were abundant.

Industrial production heavily influenced the development of 19th-century European decorative arts. Thanks to new technologies many objects were mass-produced and could be sold at more competitive prices than handmade works. Therefore more people than ever before had access to decorative objects. As a result, during the second half of the 19th century a supposed decline of taste proliferated and was lamented in Europe, especially during the world exhibitions. In this context traditional craftsmanship from the Islamic world was seen very positively and as such played a vital role in the Viennese world exhibition of 1873 where a “Persischer Pavilion” — a space especially installed for the exhibition displaying products of Persian craftsmanship — was featured prominently.

The organizers placed a special focus on the representation of the arts that were considered to be “Oriental” because of their high quality and because they could be used as models by the Austro-Hungarian industry. Many museums acquired art at the 1873 fair as they had at previous events in London and Paris. Parts of the famous Hamzename (1558–1573), a splendid Mughal Indian manuscript commissioned by the Great Mughal Akbar, were sent from Persia for the Vienna fair, and were subsequently purchased by the Museum für Kunst und Industrie.

Lavishly illustrated, this masterwork recounts the history of Amir Hamze (PBUH), an uncle of the prophet Muhammad (PBUH), and remains today one of the masterpieces of the Museum für angewandte Kunst. Interestingly, the organizer of the Persian exhibition was Jakob Eduard Polak (1818–1891), an Austro-Bohemian physician working in Persia where he reformed medical institutions.

As a consequence of the successful display of the so-called Oriental art at the world’s fair, which was attended by Nasir al-Din Shah of Persia (ruled from 1848-96), the Orientmuseum was founded in 1874-75 as a private institution. It was largely the invention of its founder and long-term director Arthur von Scala (1845-1909), and it became only the second museum in Europe dedicated entirely to the arts of what was then perceived as the Orient, including East Asia and the Islamic world. In 1907 large parts of the museum collection were integrated into the Museum für Kunst und Industrie.

The later 19th century also experienced the creation of Vienna’s large museums into which both the imperial and other private collections were integrated. Objects from the Islamic world, thus also modern-day Iran, that had existed in Vienna for centuries were distributed to the new museums, namely the Kunsthistorische Museum and the Naturhistorische Museum (opened in 1889). The creation of these museums was motivated by an aim to educate the subjects of the emperor, at this point Franz Joseph I, and to show them his splendours. By publicly displaying his possessions and sharing his knowledge with the people of Austria didactically, he became, in a way, the first teacher of his subjects.

The above is a lightly edited version of part of a chapter titled, ‘Persian Art in 19th-century Vienna’, from a book titled, ‘The Shaping of Persian Art: Collections and Interpretations of the Art of Islamic Iran and Central Asia’ edited by Yuka Kadoi and Iván Szántó, published by Cambridge Scholars Publishing.