Frederick present era bearing striking resemblance

Balancing classics, adaptation in Iranian theater

IRAN DAILY: According to directors, free theatrical adaptation makes it easier to present a more audience-friendly performance. What is your view?

HAMIDREZA NAIMI: I disagree with this conclusion. Why should we limit or expand plays like ‘Enemy of the People,’ ‘Doll’s House,’ ‘A View from the Bridge,’ ‘A Streetcar Named Desire,’ ‘Life of Galileo,’ and numerous other beautiful plays that are actually audience-friendly with their excellent concepts? This approach does not apply to all plays and productions. When Hamid Samandarian attended my theatrical adaptation of William Shakespeare’s ‘King Lear,’ he said that classical and neo-classical works have no choice but to be adapted or dramatized for contemporary life. Sometimes, in contemporary plays, due to political, and ideological reasons, and the challenges that may reflect a part of a play with the situation of our society and the censorship, or in terms of the duration of the performance, the director may be forced to delete certain parts of the work in the performance, which, in my opinion, should not be criticized as inherently non-audience-friendly. While being audience-friendly can enhance the power of a work rather than being a weakness or a sign of triviality.

I remember Claus Peymann’s direction of ‘Richard II,’ performed at Vahdat Hall in 230 minutes, and Iranian audiences, including myself, were thrilled by watching it. This can truly be an example of audience-friendliness. For all intents and purposes, do we create a work to please the general audience or to get them away from the stage. In the works I have directed, I try to pay attention to both the “unspecialized audience,” referring to the general viewer, and the “specialized audience,” whom we call the astute viewer. And this makes the theatrical production more challenging.

How do you compare the Iranian audience’s interest in adaptations and local works?

Basically, the monitoring, evaluation, and governmental systems hinder the growth of Iranian playwrights. They show no mercy or compassion in giving permits to works by Iranian authors. They don’t allow playwrights to freely write about political and social crises or adapt from classical Persian literary works or historical events.

In these circumstances, many local plays that are staged are either neutral, superficial, or have a significant gap in understanding the audience’s awareness of the society’s conditions. Iranian directors have no choice but to turn to staging translated or adapted foreign plays, classical and neo-classical works, or foreign novels and stories. This is due to the necessity imposed on Iranian directors. Although there are various sources for adaptation, there is no hope of obtaining a permit. I consider Iranian audience’s enthusiasm for the works of Bahram Beizaei, Qotbeddin Sadeqi, Mohammad Rahmanian, Mohammad Yaqoubi, and others, who have written and worked on Iranian pieces, to be on par with the works of figures like Samandarian, Ali Rafiei, and Rokneddin Khosravi, who have staged foreign plays.

Audiences seek to watch brilliant performances, whether Iranian or foreign. Personally, I may not be a supporter of Western or Eastern plays. Just as Ferdowsi, Hafez, Khayyam, Saadi, and Rumi belong to Western audiences, Homer, Sophocles, Shakespeare, and Goethe belong to Eastern people.

Given your experience in historical works, what is the reason for your interest towards Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt’s ‘Frederick or the Crime Boulevard’? Why did you choose a philosophical theater?

The very first interest of any director in staging an emotional play. Directing a work give you the feeling that you are unique, you feel delighted. This stems from the writer’s power in storytelling, dialogue writing, language, creating vibrant and dynamic characters, and the last but not least the genre of the work. The next step in selecting a piece is the form and the playwright’s idea and concept. A director reads hundreds of plays, but through thought of a few works he undergo a paradigm shift in his thinking. Likewise, reading the play ‘Frederick,’ I was emotionally and intellectually preoccupied. Its tone and the atmosphere of comedic sections, which brightened the exhausted spirits of our current days, convinced me that its performance is a “necessity.” By all means, this melodramatic play is not as philosophical as the works of Jean-Paul Sartre or Albert Camus or Samuel Beckett, but undoubtedly, the characters in this play have their own philosophies. Another aspect I appreciated was that, this time, I wanted the audience would become acquainted with the behind-the-scenes, the production process, rehearsals and performance of the play.

Discuss the challenges of staging theaters like ‘Frederick’. Is it more difficult compared to Iranian plays?

Producing an Iranian play doesn’t differ much from staging a foreign one. Undoubtedly, the most significant challenge is the lack of financial resources and government support for state theaters. The majority of a director’s creativity, energy, ability, and time are devoted to find sponsorship and funding for the production. Approximately 70% of my energy and mental focus were dedicated to borrowing the required $20,000 for this production. This work is the result of 30% of my creativity and focus.

Looking back, I see that our 30% effort as Iranian directors is equivalent to 100% effort by foreign directors who, without any stress or worry, focus on creating their works. Theater artists are the forgotten people of Iran. Their challenging profession and beautiful art seem to have no value in the eyes of art authorities. We and our art matter only to ourselves and the audience we have.

I don’t know how far we can continue this situation, but undoubtedly, we are in the darkest period of Iranian theater. A time when no official cares about culture, literature, arts, and education. A time when all the resources of this country are plundered without ensuring the basic necessities of life, such as genetic health, proper breathing, safe drinking and eating, proper sleep, reading, and thinking. Now that we are left to ourselves, I wish we had the freedom of thought and expression to raise our voices. Hopelessness about the future, job insecurity, unemployment, and lack of income are the biggest obstacles facing theater families.

The idea for this project dates back to 2019 and experienced years old hiatus before coming to fruition. What were the reasons, and what distinguishes the initial work from the one that eventually hit the stage on November 28, 2023?

In 2019, everything was ready for performance. We were preparing for mise-en-scène, costumes, and advertising, that the spread of the COVID-19 stopped the performance on March 26, 2020. In the following three years, despite officials’ insistence, I did not find the conditions suitable for staging this work. During this five-year hiatus, the script remained unchanged, but as a director, I underwent changes in terms of age, literacy, and artistic taste. Set design, costumes, music, actors movement, creating characters for stage workers, changing some actors, adding singers and dancers to the performance, and of course, my own role as “Frederick,” are among the significant changes.

In the initial week of Frederick’s ticket sales, the play managed to achieve a revenue of $4,300. What’s behind this warm reception in this short period?

I never consider the sales of a play as the only criterion for its value. The opinions of critics and experts matter, and audience reception is crucial for the life of a theatrical work. Shaya Theater Group has a 30-year history, founded by individuals like Shahram Karami, Yaghoub Sabaahi, Behnaz Nazi, Hamidreza Azarang, Mandana Abqari, and myself during our college days. Over the years, we’ve invited individuals, some of whom are still with us, including Shabnam Moqaddami, and Kambiz Amini.

Certainly, the enduring success and stability of the group, along with the effort to create brilliant, thoughtful, and impactful works, are not hidden from the eyes of the Iranian audience. In ‘Frederick,’ we may not have a familiar face from television or cinema, but our credibility assures the audience that they can trust our shows from the very beginning. Obviously, the continuation of the reception depends on direct interaction with the audience. If the work is not good, audience won’t recommend it to others.

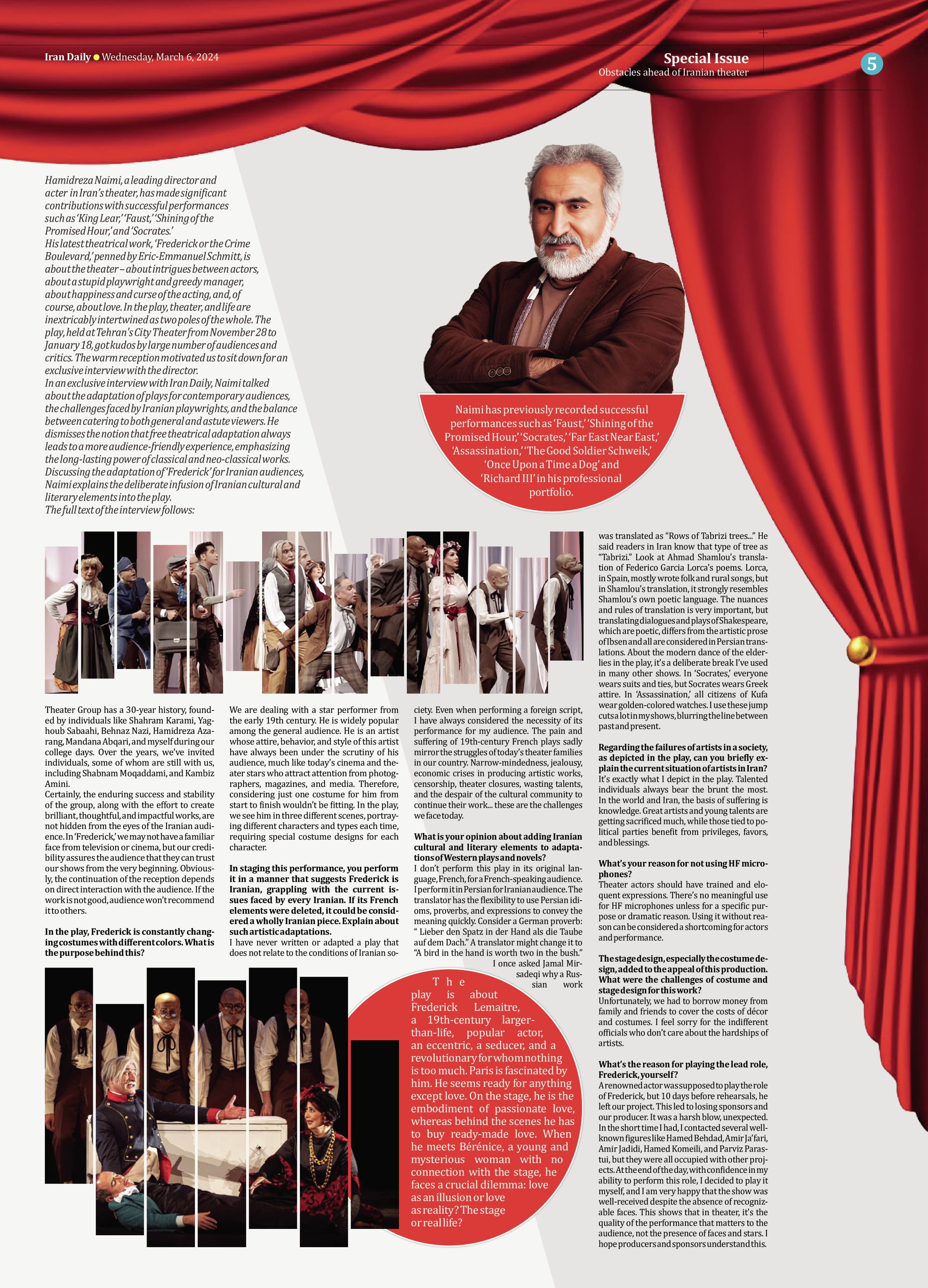

In the play, Frederick is constantly changing costumes with different colors. What is the purpose behind this?

We are dealing with a star performer from the early 19th century. He is widely popular among the general audience. He is an artist whose attire, behavior, and style of this artist have always been under the scrutiny of his audience, much like today’s cinema and theater stars who attract attention from photographers, magazines, and media. Therefore, considering just one costume for him from start to finish wouldn’t be fitting. In the play, we see him in three different scenes, portraying different characters and types each time, requiring special costume designs for each character.

In staging this performance, you perform it in a manner that suggests Frederick is Iranian, grappling with the current issues faced by every Iranian. If its French elements were deleted, it could be considered a wholly Iranian piece. Explain about such artistic adaptations.

I have never written or adapted a play that does not relate to the conditions of Iranian society. Even when performing a foreign script, I have always considered the necessity of its performance for my audience. The pain and suffering of 19th-century French plays sadly mirror the struggles of today’s theater families in our country. Narrow-mindedness, jealousy, economic crises in producing artistic works, censorship, theater closures, wasting talents, and the despair of the cultural community to continue their work... these are the challenges we face today.

What is your opinion about adding Iranian cultural and literary elements to adaptations of Western plays and novels?

I don’t perform this play in its original language, French, for a French-speaking audience. I perform it in Persian for Iranian audience. The translator has the flexibility to use Persian idioms, proverbs, and expressions to convey the meaning quickly. Consider a German proverb: “ Lieber den Spatz in der Hand als die Taube auf dem Dach.” A translator might change it to “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.” I once asked Jamal Mirsadeqi why a Russian work was translated as “Rows of Tabrizi trees...” He said readers in Iran know that type of tree as “Tabrizi.” Look at Ahmad Shamlou’s translation of Federico Garcia Lorca’s poems. Lorca, in Spain, mostly wrote folk and rural songs, but in Shamlou’s translation, it strongly resembles Shamlou’s own poetic language. The nuances and rules of translation is very important, but translating dialogues and plays of Shakespeare, which are poetic, differs from the artistic prose of Ibsen and all are considered in Persian translations. About the modern dance of the elderlies in the play, it’s a deliberate break I’ve used in many other shows. In ‘Socrates,’ everyone wears suits and ties, but Socrates wears Greek attire. In ‘Assassination,’ all citizens of Kufa wear golden-colored watches. I use these jump cuts a lot in my shows, blurring the line between past and present.

Regarding the failures of artists in a society, as depicted in the play, can you briefly explain the current situation of artists in Iran?

It’s exactly what I depict in the play. Talented individuals always bear the brunt the most. In the world and Iran, the basis of suffering is knowledge. Great artists and young talents are getting sacrificed much, while those tied to political parties benefit from privileges, favors, and blessings.

What’s your reason for not using HF microphones?

Theater actors should have trained and eloquent expressions. There’s no meaningful use for HF microphones unless for a specific purpose or dramatic reason. Using it without reason can be considered a shortcoming for actors and performance.

The stage design, especially the costume design, added to the appeal of this production. What were the challenges of costume and stage design for this work?

Unfortunately, we had to borrow money from family and friends to cover the costs of décor and costumes. I feel sorry for the indifferent officials who don’t care about the hardships of artists.

What’s the reason for playing the lead role, Frederick, yourself?

A renowned actor was supposed to play the role of Frederick, but 10 days before rehearsals, he left our project. This led to losing sponsors and our producer. It was a harsh blow, unexpected. In the short time I had, I contacted several well-known figures like Hamed Behdad, Amir Ja’fari, Amir Jadidi, Hamed Komeili, and Parviz Parastui, but they were all occupied with other projects. At the end of the day, with confidence in my ability to perform this role, I decided to play it myself, and I am very happy that the show was well-received despite the absence of recognizable faces. This shows that in theater, it’s the quality of the performance that matters to the audience, not the presence of faces and stars. I hope producers and sponsors understand this.

Hamidreza Naimi, a leading director and acter in Iran’s theater, has made significant contributions with successful performances such as ‘King Lear,’ ‘Faust,’ ‘Shining of the Promised Hour,’ and ‘Socrates.’

His latest theatrical work, ‘Frederick or the Crime Boulevard,’ penned by Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt, is about the theater – about intrigues between actors, about a stupid playwright and greedy manager, about happiness and curse of the acting, and, of course, about love. In the play, theater, and life are inextricably intertwined as two poles of the whole. The play, held at Tehran's City Theater from November 28 to January 18, got kudos by large number of audiences and critics. The warm reception motivated us to sit down for an exclusive interview with the director.

In an exclusive interview with Iran Daily, Naimi talked about the adaptation of plays for contemporary audiences, the challenges faced by Iranian playwrights, and the balance between catering to both general and astute viewers. He dismisses the notion that free theatrical adaptation always leads to a more audience-friendly experience, emphasizing the long-lasting power of classical and neo-classical works. Discussing the adaptation of ‘Frederick’ for Iranian audiences, Naimi explains the deliberate infusion of Iranian cultural and literary elements into the play.

The full text of the interview follows: