Evolution of artistic innovations in bronze articles and architectural epigraphy

The appearance of living creatures on bronze articles constitutes an evident innovation, insofar as there is a large group of bronze articles dating from the end of the 11th centuries from the eastern regions of Iran (possibly from Khorasan in the first instance), which are decorated only with geometrical ornament of circles and dots.

At the outset there are no inscriptions on pieces in this group. Arabic inscriptions only appear at a later stage. In actual fact, only one scoop of this type is known, but its ornament of circles and dots no longer plays an independent role, serving only to fill in the background to the inscription, which associates this scoop with another group of bowls, since they also have a similar background to several inscriptions.

This fact attests to the geographical proximity of the two groups in question. Thus, around the end of the 10th century the number of items with geometrical ornamentation decreases and items appear with inscriptions.

A group of bronze items, consisting of bowls and trays, was manufactured in Mavera al-Nahr (Central Asia). It should be mentioned here because it undergoes changes over the course of the 11th century: the bowls become more massive, the background ornament to the inscriptions becomes finer and the character of the script changes slightly. However, there are no depictions of living creatures on items of this group during the 10th and 11th centuries. It is essential to point out one general feature of all three groups of bronze articles produced in neighbouring areas during the 10th and 11th centuries and that is the absence of inlay. Inlay appears on Iranian (Khorasan) items only in the 11th century and flourishes magnificently during the 12th century. This fact also supports the proposed periodic classification.

Early pieces inlaid with copper and silver – such as the figure of an eagle dating from 180 AH (796-797 CE), or the ewer from Svaneti, and other objects of the 7th-9th centuries – if associated with Iranian territory, are more likely to have come from its western rather than eastern regions, but they were probably manufactured somewhere in Iraq, the centre of the Caliphate.

The absence of precisely dated examples hinders any assessment of changes in ceramics and textiles, and in this instance archaeological methods do not provide the necessary precision. The question of a periodic classification for architecture has concerned scholars for a long time. During the 11th and 12th centuries great changes can be observed in architectural epigraphy. In the 11th century, the Kufic script becomes more complicated and the so-called “plaited” Kufic makes its appearance.

It is possible that the first examples in architecture are to be assigned to the early 11th century (for example, at Rabati Malik), although in ceramics “plaited” Kufic script is already well represented in the 10th century. At the same time naskhi writing begins to be used as a monumental script. It has also been established that during the 11th century specific types of mosque, madreseh (mosque school) and minaret became prevalent throughout Iran, though these types were not genuinely new but had already been developed during the preceding ages. In the sphere of architectural decor much that is new emerges in the 11th century, and frequently these innovations occur during the period preceding the creation of the great Seljuk empire.

It has been suggested that radical changes took place in art with the consolidation of Seljuk power.

But as we have attempted to show, these changes were already perceptible much earlier, before the founding of the Seljuk state in eastern Iran. The Seljuks’ contribution to art appears to have been very small; it is even difficult to speak of the Seljuk sultans’ patronage of art as their dynasty never founded a permanent capital city which would have become a centre for the artistic movements of the period.

The changes in Persian art coincide chronologically with the Seljuk conquest, but it is necessary to seek the cause of these changes in the life of the Iranian cities where craftsmen and artists congregated. But by founding an empire from the Amu Darya (Oxus) River to the Mediterranean, the Seljuks furthered the spread of Persian art to the west.

A large number of Iranian craftsmen moved to Iraq and Anatolia in the 11th and 12th centuries and collaborated in the creation of a new style in these areas (another group of craftsmen went to the western regions a little later, at the time of the Mongol invasion).

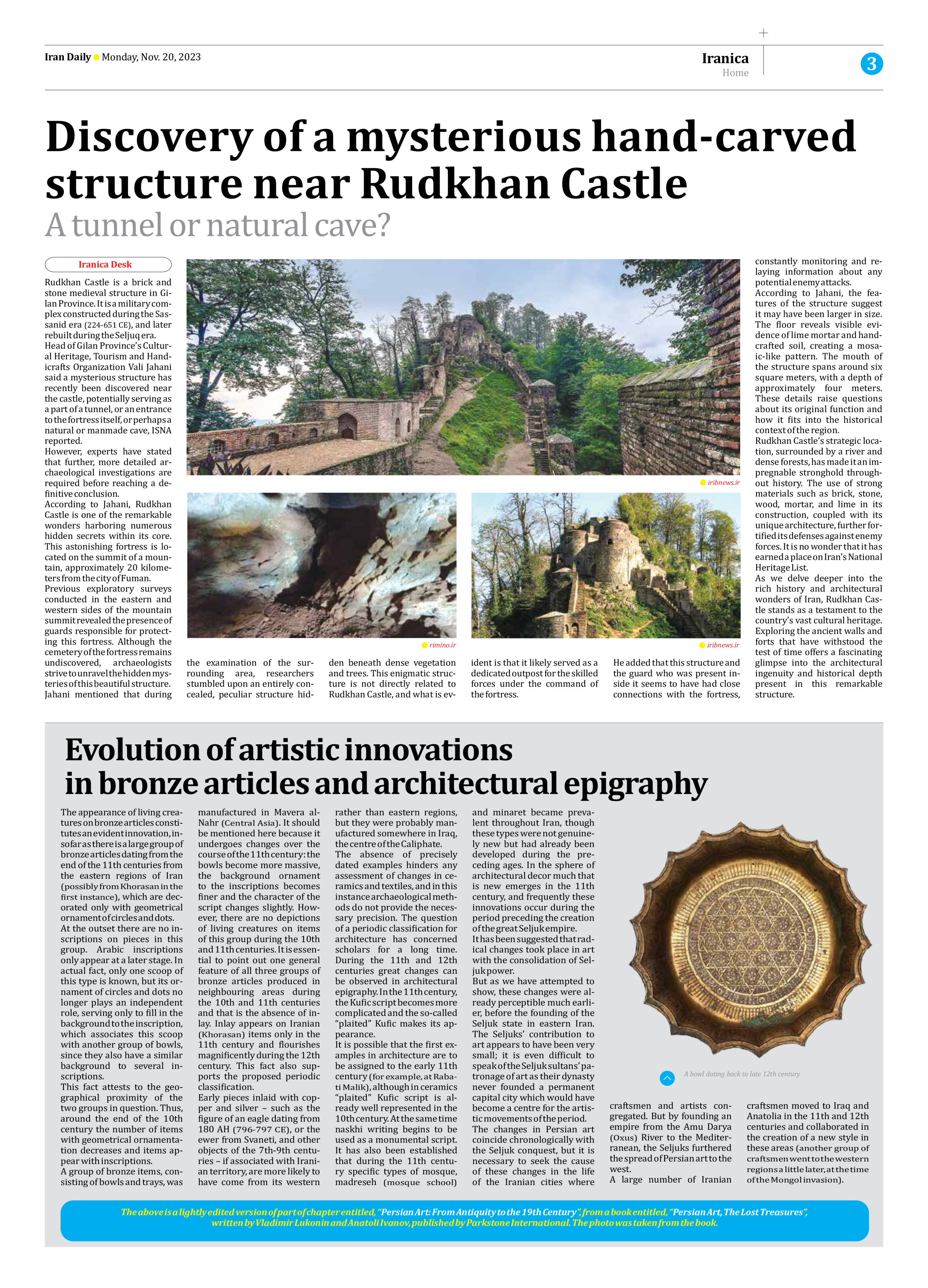

The above is a lightly edited version of part of chapter entitled, “Persian Art: From Antiquity to the 19th Century”, from a book entitled, “Persian Art, The Lost Treasures”,

written by Vladimir Lukonin and Anatoli Ivanov, published by Parkstone International. The photo was taken from the book.