Iranian photojournalist Fereydoun Ganjour:

‘A war photographer should be a soldier first’

Ali Amiri

Staff writer

On the eventful noon of September 22, 1980, the Iraqi Air Force launched a surprise airstrike on Iran, thus beginning a war on a nation that had recently seen the fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty through the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

The war waged on Iran by the Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein lasted until August 1988 – a decisive period in the history of Iran known as the Sacred Defense.

To commemorate the bravery and sacrifice made by the Iranian soldiers and commanders during the war, Iran annually observes a week-long memorial named Sacred Defense Week, which starts on September 22.

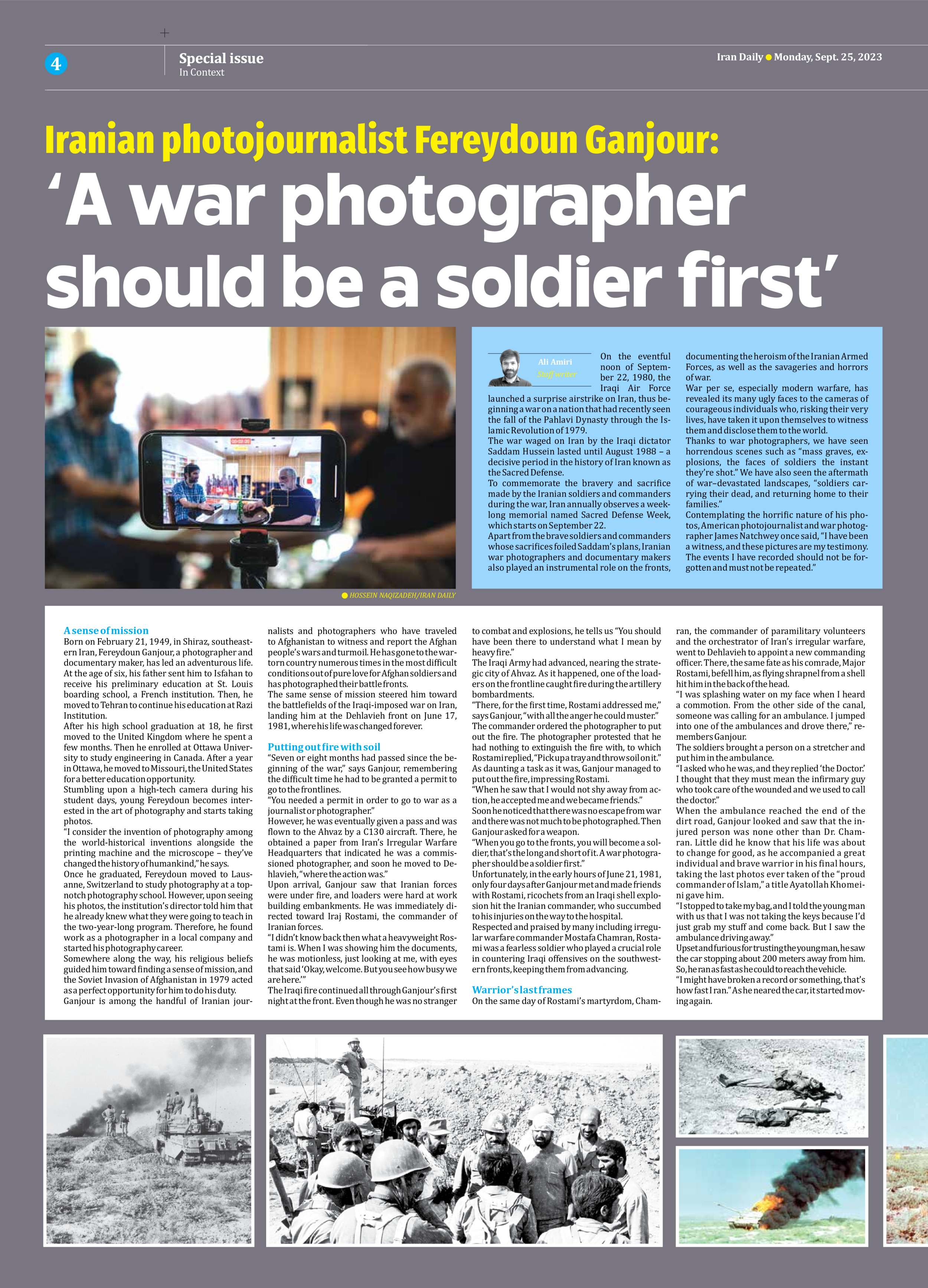

Apart from the brave soldiers and commanders whose sacrifices foiled Saddam’s plans, Iranian war photographers and documentary makers also played an instrumental role on the fronts, documenting the heroism of the Iranian Armed Forces, as well as the savageries and horrors of war.

War per se, especially modern warfare, has revealed its many ugly faces to the cameras of courageous individuals who, risking their very lives, have taken it upon themselves to witness them and disclose them to the world.

Thanks to war photographers, we have seen horrendous scenes such as “mass graves, explosions, the faces of soldiers the instant they’re shot.” We have also seen the aftermath of war–devastated landscapes, “soldiers carrying their dead, and returning home to their families.”

Contemplating the horrific nature of his photos, American photojournalist and war photographer James Natchwey once said, “I have been a witness, and these pictures are my testimony. The events I have recorded should not be forgotten and must not be repeated.”

A sense of mission

Born on February 21, 1949, in Shiraz, southeastern Iran, Fereydoun Ganjour, a photographer and documentary maker, has led an adventurous life. At the age of six, his father sent him to Isfahan to receive his preliminary education at St. Louis boarding school, a French institution. Then, he moved to Tehran to continue his education at Razi Institution.

After his high school graduation at 18, he first moved to the United Kingdom where he spent a few months. Then he enrolled at Ottawa University to study engineering in Canada. After a year in Ottawa, he moved to Missouri, the United States for a better education opportunity.

Stumbling upon a high-tech camera during his student days, young Fereydoun becomes interested in the art of photography and starts taking photos.

“I consider the invention of photography among the world-historical inventions alongside the printing machine and the microscope – they’ve changed the history of humankind,” he says.

Once he graduated, Fereydoun moved to Lausanne, Switzerland to study photography at a top-notch photography school. However, upon seeing his photos, the institution’s director told him that he already knew what they were going to teach in the two-year-long program. Therefore, he found work as a photographer in a local company and started his photography career.

Somewhere along the way, his religious beliefs guided him toward finding a sense of mission, and the Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 acted as a perfect opportunity for him to do his duty.

Ganjour is among the handful of Iranian journalists and photographers who have traveled to Afghanistan to witness and report the Afghan people’s wars and turmoil. He has gone to the war-torn country numerous times in the most difficult conditions out of pure love for Afghan soldiers and has photographed their battle fronts.

The same sense of mission steered him toward the battlefields of the Iraqi-imposed war on Iran, landing him at the Dehlavieh front on June 17, 1981, where his life was changed forever.

Putting out fire with soil

“Seven or eight months had passed since the beginning of the war,” says Ganjour, remembering the difficult time he had to be granted a permit to go to the frontlines.

“You needed a permit in order to go to war as a journalist or photographer.”

However, he was eventually given a pass and was flown to the Ahvaz by a C130 aircraft. There, he obtained a paper from Iran’s Irregular Warfare Headquarters that indicated he was a commissioned photographer, and soon he moved to Dehlavieh, “where the action was.”

Upon arrival, Ganjour saw that Iranian forces were under fire, and loaders were hard at work building embankments. He was immediately directed toward Iraj Rostami, the commander of Iranian forces.

“I didn’t know back then what a heavyweight Rostami is. When I was showing him the documents, he was motionless, just looking at me, with eyes that said ‘Okay, welcome. But you see how busy we are here.’”

The Iraqi fire continued all through Ganjour’s first night at the front. Even though he was no stranger to combat and explosions, he tells us “You should have been there to understand what I mean by heavy fire.”

The Iraqi Army had advanced, nearing the strategic city of Ahvaz. As it happened, one of the loaders on the frontline caught fire during the artillery bombardments.

“There, for the first time, Rostami addressed me,” says Ganjour, “with all the anger he could muster.”

The commander ordered the photographer to put out the fire. The photographer protested that he had nothing to extinguish the fire with, to which Rostami replied, “Pick up a tray and throw soil on it.”

As daunting a task as it was, Ganjour managed to put out the fire, impressing Rostami.

“When he saw that I would not shy away from action, he accepted me and we became friends.”

Soon he noticed that there was no escape from war and there was not much to be photographed. Then Ganjour asked for a weapon.

“When you go to the fronts, you will become a soldier, that’s the long and short of it. A war photographer should be a soldier first.”

Unfortunately, in the early hours of June 21, 1981, only four days after Ganjour met and made friends with Rostami, ricochets from an Iraqi shell explosion hit the Iranian commander, who succumbed to his injuries on the way to the hospital.

Respected and praised by many including irregular warfare commander Mostafa Chamran, Rostami was a fearless soldier who played a crucial role in countering Iraqi offensives on the southwestern fronts, keeping them from advancing.

Warrior’s last frames

On the same day of Rostami’s martyrdom, Chamran, the commander of paramilitary volunteers and the orchestrator of Iran’s irregular warfare, went to Dehlavieh to appoint a new commanding officer. There, the same fate as his comrade, Major Rostami, befell him, as flying shrapnel from a shell hit him in the back of the head.

“I was splashing water on my face when I heard a commotion. From the other side of the canal, someone was calling for an ambulance. I jumped into one of the ambulances and drove there,” remembers Ganjour.

The soldiers brought a person on a stretcher and put him in the ambulance.

“I asked who he was, and they replied ‘the Doctor.’ I thought that they must mean the infirmary guy who took care of the wounded and we used to call the doctor.”

When the ambulance reached the end of the dirt road, Ganjour looked and saw that the injured person was none other than Dr. Chamran. Little did he know that his life was about to change for good, as he accompanied a great individual and brave warrior in his final hours, taking the last photos ever taken of the “proud commander of Islam,” a title Ayatollah Khomeini gave him.

“I stopped to take my bag, and I told the young man with us that I was not taking the keys because I’d just grab my stuff and come back. But I saw the ambulance driving away.”

Upset and furious for trusting the young man, he saw the car stopping about 200 meters away from him. So, he ran as fast as he could to reach the vehicle.

“I might have broken a record or something, that’s how fast I ran.” As he neared the car, it started moving again.

“I threw my bag into the car and then pulled myself up. I was hanging from the car for quite a while.” Ganjour started filming and taking pictures of Chamran as soon as he regained his breath.

“I filmed it all. Since he was on the stretcher to the surgery room. The wound he had was not deep, and Dr. Chamran had no trouble breathing in the ambulance or the clinic,” recalls Ganjour.

“The wound on his head was minor, as it was apparent from a spoonful of blood on the bandage. The first mistake the medical staff made was they opened the bandage on his head.” Then, as Ganjour recalls, they made another mistake and clumsily put a tube in the Chamran’s mouth, “a pointless act as he had no trouble breathing.”

As they inserted the tube, Chamran got up and sat on the stretcher, with no one minding him from the back.

“Then Dr. Chamran fell and the wound on his head was cut open, and he was martyred due to the bleeding as he was being taken away.” Ganjour stopped filming and turned to the young medical staff.

“I asked him ‘Are you a doctor,’ to which he replied after a pause, ‘No, I’m an operating theater technician.”

After Chamran’s martyrdom, Ganjour returned to Ahvaz for his funeral, and there met Chamran’s younger brother and Kazem Akhavan – a fearless Iranian photojournalist – for the first time.

“The sadness we all felt was insurmountable. The loss of Dr. Chamran fell incredibly heavy on our hearts.”