Development of Sassanid art

Looking at Sassanid art as a whole, one reaches the conclusion that it began with a fairly limited range of themes strictly stratified according to genre, as an art that was, so to speak, “conceptual”, or at any rate subject to an absolutely specific interpretation, and “imperial”, an instrument for political propaganda. In late Sassanid art, however, genres blend; complex religious symbolism changes into benedictory symbolism; the symbolic banquet, battles and hunting scenes become ordinary tales of hunting exploits, many feasts and chivalry.

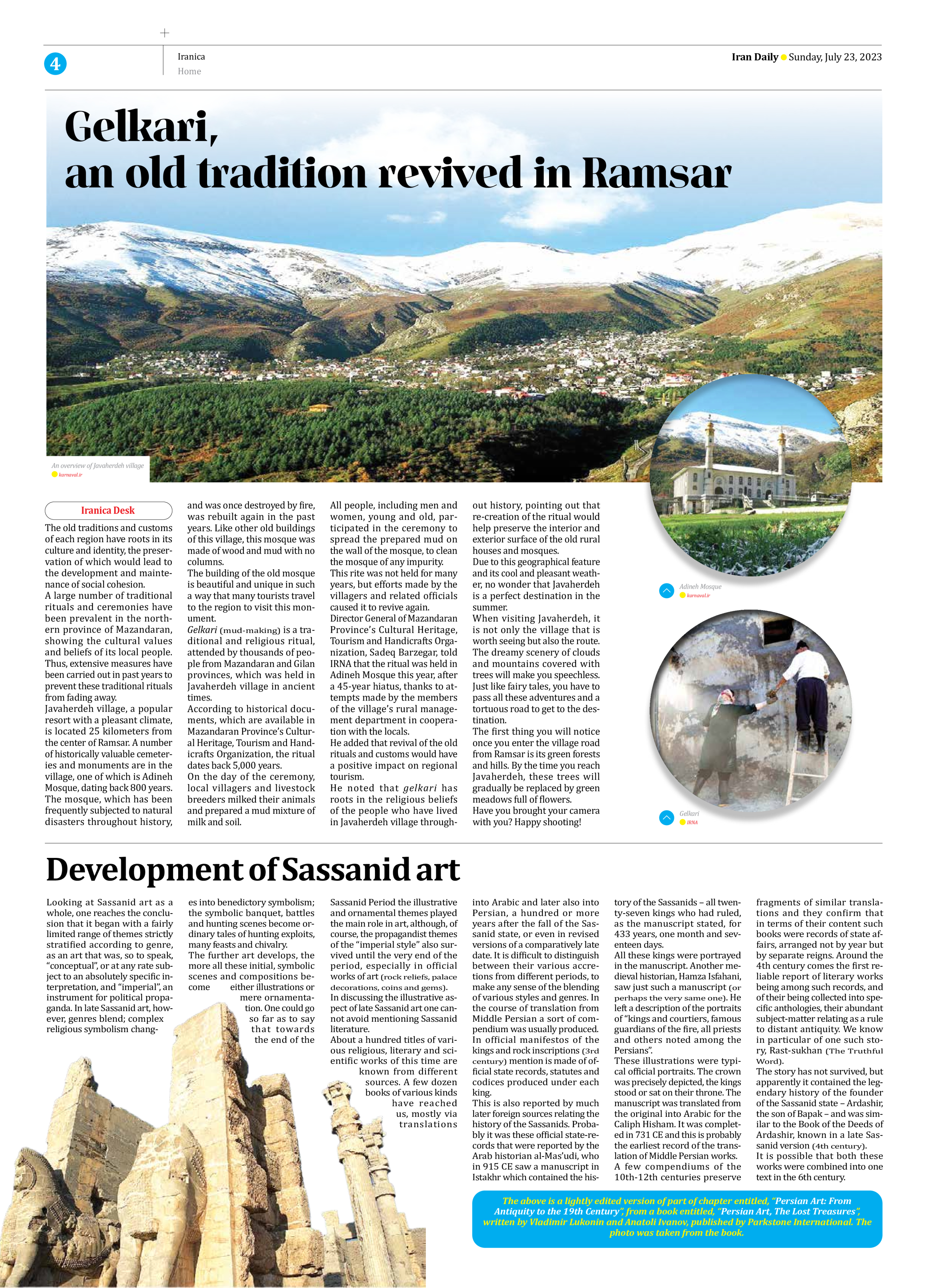

The further art develops, the more all these initial, symbolic scenes and compositions become either illustrations or mere ornamentation. One could go so far as to say that towards the end of the Sassanid Period the illustrative and ornamental themes played the main role in art, although, of course, the propagandist themes of the “imperial style” also survived until the very end of the period, especially in official works of art (rock reliefs, palace decorations, coins and gems).

In discussing the illustrative aspect of late Sassanid art one cannot avoid mentioning Sassanid literature.

About a hundred titles of various religious, literary and scientific works of this time are known from different sources. A few dozen books of various kinds have reached us, mostly via translations into Arabic and later also into Persian, a hundred or more years after the fall of the Sassanid state, or even in revised versions of a comparatively late date. It is difficult to distinguish between their various accretions from different periods, to make any sense of the blending of various styles and genres. In the course of translation from Middle Persian a sort of compendium was usually produced.

In official manifestos of the kings and rock inscriptions (3rd century) mention is made of official state records, statutes and codices produced under each king.

This is also reported by much later foreign sources relating the history of the Sassanids. Probably it was these official state-records that were reported by the Arab historian al-Mas’udi, who in 915 CE saw a manuscript in Istakhr which contained the history of the Sassanids – all twenty-seven kings who had ruled, as the manuscript stated, for 433 years, one month and seventeen days.

All these kings were portrayed in the manuscript. Another medieval historian, Hamza Isfahani, saw just such a manuscript (or perhaps the very same one). He left a description of the portraits of “kings and courtiers, famous guardians of the fire, all priests and others noted among the Persians”.

These illustrations were typical official portraits. The crown was precisely depicted, the kings stood or sat on their throne. The manuscript was translated from the original into Arabic for the Caliph Hisham. It was completed in 731 CE and this is probably the earliest record of the translation of Middle Persian works.

A few compendiums of the 10th-12th centuries preserve fragments of similar translations and they confirm that in terms of their content such books were records of state affairs, arranged not by year but by separate reigns. Around the 4th century comes the first reliable report of literary works being among such records, and of their being collected into specific anthologies, their abundant subject-matter relating as a rule to distant antiquity. We know in particular of one such story, Rast-sukhan (The Truthful Word).

The story has not survived, but apparently it contained the legendary history of the founder of the Sassanid state – Ardashir, the son of Bapak – and was similar to the Book of the Deeds of Ardashir, known in a late Sassanid version (4th century).

It is possible that both these works were combined into one text in the 6th century.

The above is a lightly edited version of part of chapter entitled, “Persian Art: From Antiquity to the 19th Century”, from a book entitled, “Persian Art, The Lost Treasures”, written by Vladimir Lukonin and Anatoli Ivanov, published by Parkstone International. The photo was taken from the book.