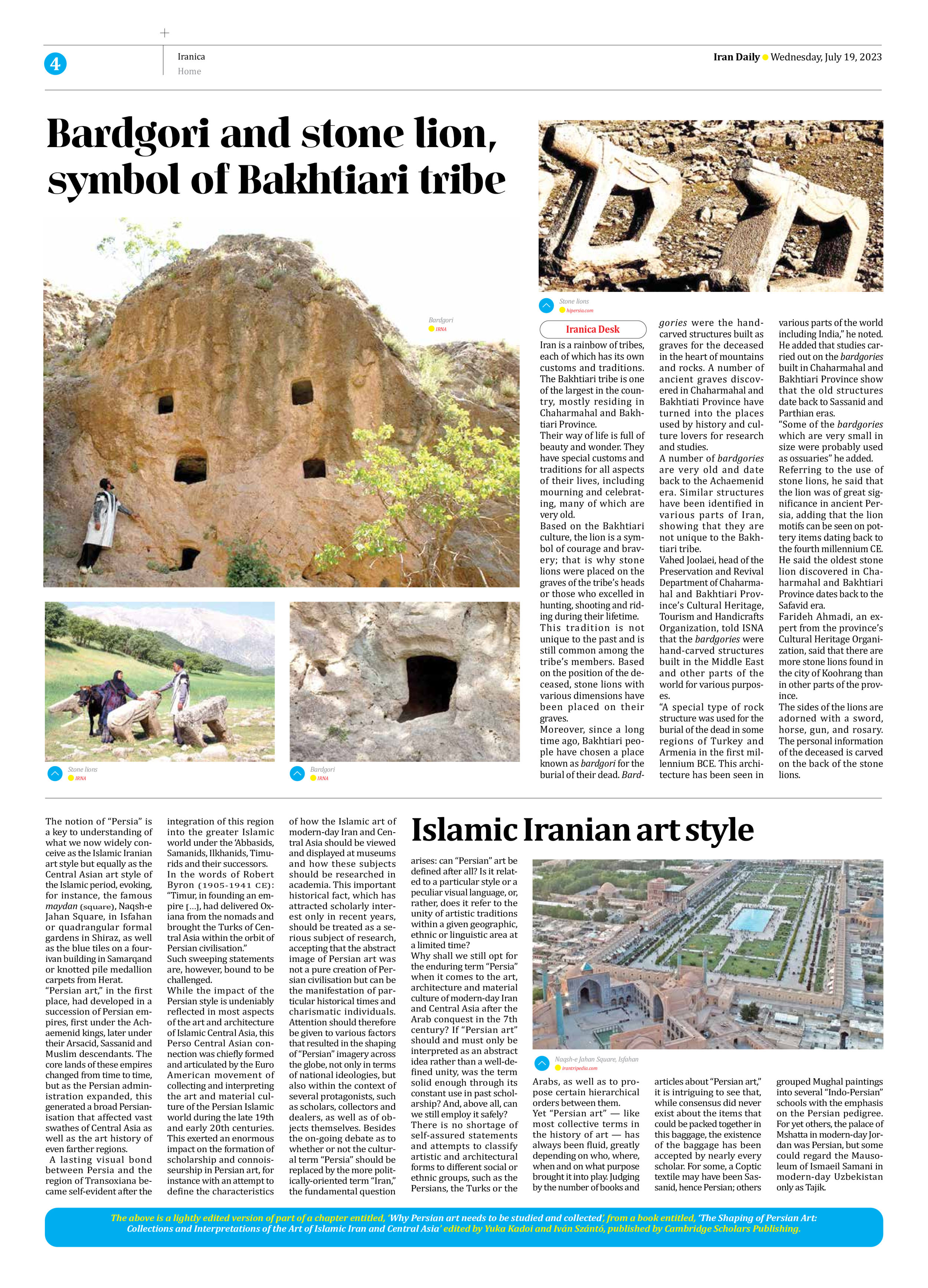

Islamic Iranian art style

The notion of “Persia” is a key to understanding of what we now widely conceive as the Islamic Iranian art style but equally as the Central Asian art style of the Islamic period, evoking, for instance, the famous maydan (square), Naqsh-e Jahan Square, in Isfahan or quadrangular formal gardens in Shiraz, as well as the blue tiles on a four-ivan building in Samarqand or knotted pile medallion carpets from Herat.

“Persian art,” in the first place, had developed in a succession of Persian empires, first under the Achaemenid kings, later under their Arsacid, Sassanid and Muslim descendants. The core lands of these empires changed from time to time, but as the Persian administration expanded, this generated a broad Persianisation that affected vast swathes of Central Asia as well as the art history of even farther regions.

A lasting visual bond between Persia and the region of Transoxiana became self-evident after the integration of this region into the greater Islamic world under the ‘Abbasids, Samanids, Ilkhanids, Timurids and their successors.

In the words of Robert Byron (1905-1941 CE): “Timur, in founding an empire […], had delivered Oxiana from the nomads and brought the Turks of Central Asia within the orbit of Persian civilisation.”

Such sweeping statements are, however, bound to be challenged.

While the impact of the Persian style is undeniably reflected in most aspects of the art and architecture of Islamic Central Asia, this Perso Central Asian connection was chiefly formed and articulated by the Euro American movement of collecting and interpreting the art and material culture of the Persian Islamic world during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This exerted an enormous impact on the formation of scholarship and connoisseurship in Persian art, for instance with an attempt to define the characteristics of how the Islamic art of modern-day Iran and Central Asia should be viewed and displayed at museums and how these subjects should be researched in academia. This important historical fact, which has attracted scholarly interest only in recent years, should be treated as a serious subject of research, accepting that the abstract image of Persian art was not a pure creation of Persian civilisation but can be the manifestation of particular historical times and charismatic individuals. Attention should therefore be given to various factors that resulted in the shaping of “Persian” imagery across the globe, not only in terms of national ideologies, but also within the context of several protagonists, such as scholars, collectors and dealers, as well as of objects themselves. Besides the on-going debate as to whether or not the cultural term “Persia” should be replaced by the more politically-oriented term “Iran,” the fundamental question arises: can “Persian” art be defined after all? Is it related to a particular style or a peculiar visual language, or, rather, does it refer to the unity of artistic traditions within a given geographic, ethnic or linguistic area at a limited time?

Why shall we still opt for the enduring term “Persia” when it comes to the art, architecture and material culture of modern-day Iran and Central Asia after the Arab conquest in the 7th century? If “Persian art” should and must only be interpreted as an abstract idea rather than a well-defined unity, was the term solid enough through its constant use in past scholarship? And, above all, can we still employ it safely?

There is no shortage of self-assured statements and attempts to classify artistic and architectural forms to different social or ethnic groups, such as the Persians, the Turks or the Arabs, as well as to propose certain hierarchical orders between them.

Yet “Persian art” — like most collective terms in the history of art — has always been fluid, greatly depending on who, where, when and on what purpose brought it into play. Judging by the number of books and articles about “Persian art,” it is intriguing to see that, while consensus did never exist about the items that could be packed together in this baggage, the existence of the baggage has been accepted by nearly every scholar. For some, a Coptic textile may have been Sassanid, hence Persian; others grouped Mughal paintings into several “Indo-Persian” schools with the emphasis on the Persian pedigree. For yet others, the palace of Mshatta in modern-day Jordan was Persian, but some could regard the Mausoleum of Ismaeil Samani in modern-day Uzbekistan only as Tajik.

The above is a lightly edited version of part of a chapter entitled, ‘Why Persian art needs to be studied and collected’, from a book entitled, ‘The Shaping of Persian Art:

Collections and Interpretations of the Art of Islamic Iran and Central Asia’ edited by Yuka Kadoi and Iván Szántó, published by Cambridge Scholars Publishing.