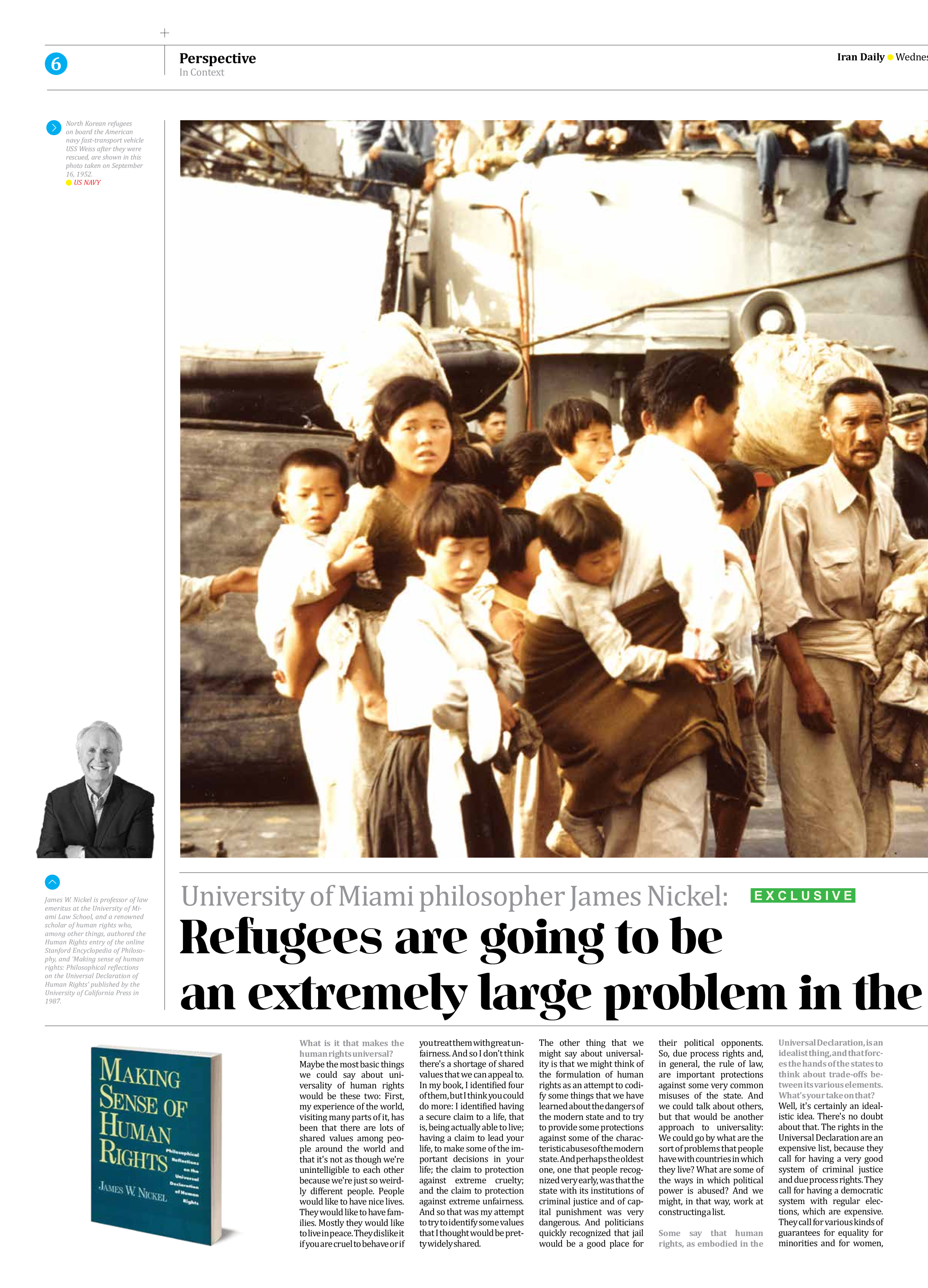

University of Miami philosopher James Nickel:

Refugees are going to be an extremely large problem in the future

What is it that makes the human rights universal?

Maybe the most basic things we could say about universality of human rights would be these two: First, my experience of the world, visiting many parts of it, has been that there are lots of shared values among people around the world and that it's not as though we're unintelligible to each other because we're just so weirdly different people. People would like to have nice lives. They would like to have families. Mostly they would like to live in peace. They dislike it if you are cruel to behave or if you treat them with great unfairness. And so I don't think there's a shortage of shared values that we can appeal to. In my book, I identified four of them, but I think you could do more: I identified having a secure claim to a life, that is, being actually able to live; having a claim to lead your life, to make some of the important decisions in your life; the claim to protection against extreme cruelty; and the claim to protection against extreme unfairness. And so that was my attempt to try to identify some values that I thought would be pretty widely shared.

The other thing that we might say about universality is that we might think of the formulation of human rights as an attempt to codify some things that we have learned about the dangers of the modern state and to try to provide some protections against some of the characteristic abuses of the modern state. And perhaps the oldest one, one that people recognized very early, was that the state with its institutions of criminal justice and of capital punishment was very dangerous. And politicians quickly recognized that jail would be a good place for their political opponents. So, due process rights and, in general, the rule of law, are important protections against some very common misuses of the state. And we could talk about others, but that would be another approach to universality: We could go by what are the sort of problems that people have with countries in which they live? What are some of the ways in which political power is abused? And we might, in that way, work at constructing a list.

Some say that human rights, as embodied in the Universal Declaration, is an idealist thing, and that forces the hands of the states to think about trade-offs between its various elements. What’s your take on that?

Well, it's certainly an idealistic idea. There's no doubt about that. The rights in the Universal Declaration are an expensive list, because they call for having a very good system of criminal justice and due process rights. They call for having a democratic system with regular elections, which are expensive. They call for various kinds of guarantees for equality for minorities and for women, and those things are difficult to achieve. And then finally, they call for the creation of a welfare state where people are provided for, where it's made sure that people are able to get food and water and education and some access to health care. And so that's something for rich countries!

But if you're in Haiti, and the average individual share of the GDP is only a few hundred dollars per person, that isn't going to be accomplished. This isn't a program that can be fully accomplished in the low income countries. So that's a that's a way in which it's idealistic: It sets high goals, and I've always been worried about the fact that it didn't really address what was to be done in poorer countries.

I'm not applying this to Iran, since Iran is not a poor country. But if you think about the low income countries in Africa, and still a few in Asia such as Cambodia, we're talking about something that goes way beyond the available resources. And of course, there are tradeoffs between liberty and equality, or between security and freedom. Then, if we're thinking about international human rights as promoted by the United Nations or by various regional organizations, that system is designed to give countries quite a lot of flexibility in dealing with trade-offs. And even there is far less room for tradeoffs if you're under the European Court of Human Rights, that is, if you've signed the European Convention. There you're under the single court, but still, the judges in that court are drawn from some 50 countries in Europe, and they, too, are prepared to give some flexibility to countries that seem to be acting in good faith.

So I don't think that the system, as we now have it, prohibits trade-offs except in a few areas. It prohibits trade-offs in regard to torture. It prohibits trade-offs in regard to political murder. Well, it prohibits trade-offs in regard to slavery. But in terms of other things, not so much.

With those in mind, do you think the human rights discourse can push back what we call authoritarianism?

I think it'll be with us for centuries. In my class the other day, in which I taught a course on international human rights at the University of Miami Law School, I said that historically most popular political philosophy is authoritarianism. That is the one that is most common in the history of most countries and is still very strong today. So the conflict between authoritarians and people who want constraints on government is one that is very much with us. And it's not going to go away. I mean, we have one of the two biggest countries in the world, China, which is very authoritarian. It has a strong central leader. It isn't very strong on due process. It penalizes political dissent. So I thought authoritarianism is real and that's very much here around the world, and the attempt to sort of create an alternative, I think, is a work in progress. But I'm committed to it.

Some critics also point to the things that happened in the US in the 21st century as evidence that even the greatest promoter of human rights fails to respect it as it should.

The United States is far from perfect. And in time of war, there can be great war fever. I experienced that after 911. The population was angry and there was a lot of fight that happened in the United States. There were people who believed in reacting with a very strong hand. So, creating a society that actually respects due process rights, that respects the right to dissent, that's a real accomplishment. It isn't something that is easy to achieve and not easy to maintain, in my opinion.

But in terms of many areas of liberty, I think the US is quite strong: In terms of personal liberty, liberty of belief, liberty of communication, it's quite strong.

The reason I pointed to that was the amount of criticism which is made of Iran in those regards.

You know, I'm not here to sort of criticize Iran. I have great respect for the Iranian people. I've known a lot of Iranians who are very talented young people. And I hope that the country will evolve in a direction that is more respectful of human rights. But that isn't going to be achieved from outside the country. That's going to be achieved from inside the country.

There is also the matter of emerging human issues which were not properly addressed in the Universal Declaration. Shouldn’t we think of making amendments in regards to changes due to, say, internet or refugee problem?

If you think about the formation of the treaties that followed the Universal Declaration, lots and lots of specific rights were added, particularly in the area of minority group rights. So there are lots and lots of specific treaties coming out of the United Nations and also coming out of the American system of human rights that deal with those issues. So you have treaties that address the rights of children. You have ones that address the issues of women. You have treaties that address the problems of people with disabilities. So there have been quite a lot of additions and there is no reason, in my opinion, why we shouldn't have evolution in our lists of specific rights, because as times change, we have new problems.

The issues about the Internet are certainly big and not ones that we foresaw when we first started talking about freedom of the press. So that's an area where we need to think, because these things aren't just some kind of panaceas that we can apply thoughtlessly. They require deliberation. We can we can deliberate, beginning with some of the underlying values, and then we can look at the list that we've constructed and we can say, what do we no longer need? Maybe we don't need the right to bear arms, which we have in our Constitution. And maybe we need to deal with other issues, such as refugees. There is international law pertaining to refugees, but it's weak. And I believe that that is going to be an extremely large problem in the future, especially if the worst of predictions of people concerned with climate change come true, because then we will have many people who have to move, who have to leave their homes and move to higher ground. And if that happens in Bangladesh, or if we have really serious problems of drought in Africa, there will be many, many millions of people on the move that will present problems that are very, very hard.

But we're already, of course, seeing it in, say, Jordan, where Jordan has been good in terms of accepting of hundreds and perhaps millions of Syrian refugees. They've built refugee camps in the desert and many people have come to the cities. But it's an incredible burden. And I really respect what they've done, what they've tried to do. But that's not easy. It's a huge inflow of refugees and it's a really big problem for a country.

And that last issue, global warming or climate change, threatens almost everyone!

Right! Nearby neighborhoods in Miami are going to be under water. Even if we get one meter of sea level rise, there'll be Miami neighborhoods that have serious flooding during high tides. So it isn't just in the Maldives.

One last political question: Sometimes it seems that the American state or media are not fair in their criticisms of human right issues across the globe when it happens to involve their allies. For example, a comparison between Iran and Saudi Arabia might be relevant here.

Well, certainly in the United States press, there's plenty of criticism of Saudi Arabia, plenty of criticism in regard to women not, allowing women to drive. They are making a little progress, I think. But the position of women in Saudi Arabia is very restricted. The other thing that we hear quite a lot about is that the Saudis did a lot to spread a very extremely conservative version of Islam. And that that has had caused some of the problems in the Middle East. It's not unnoticed that most of the 911 attackers were Saudis. And so it's not as though the Saudis aren’t criticized. I certainly hear much more criticism of Saudi Arabia than I do of Iran. The worries about Iran are much more related to military possibilities, which you understand.