Ferdowsi’ Shahnameh, well suited to pictorial interpretation

The Shahnameh ('Book of Kings') has been called 'the title-deeds of the Persian nation'. It was composed by the poet Abul-Qasem Ferdowsi Tusi, between about 980 and 1009-10. In over 50,000 rhyming couplets, it recounts the history of pre-Islamic Iran through the reigns of fifty mythical and historical kings. Ferdowsi wrote his vast epic almost entirely in the 'New Persian' language of the early medieval period; it is in one way an Iranian 'declaration of independence'.

Copies of Ferdowsi's great poem soon began to acquire special significance: It had for some centuries been transcribed with care and ornamented with precious materials, so other significant texts began to be similarly treated.

Pictures added yet another dimension to Ferdowsi's great poem.

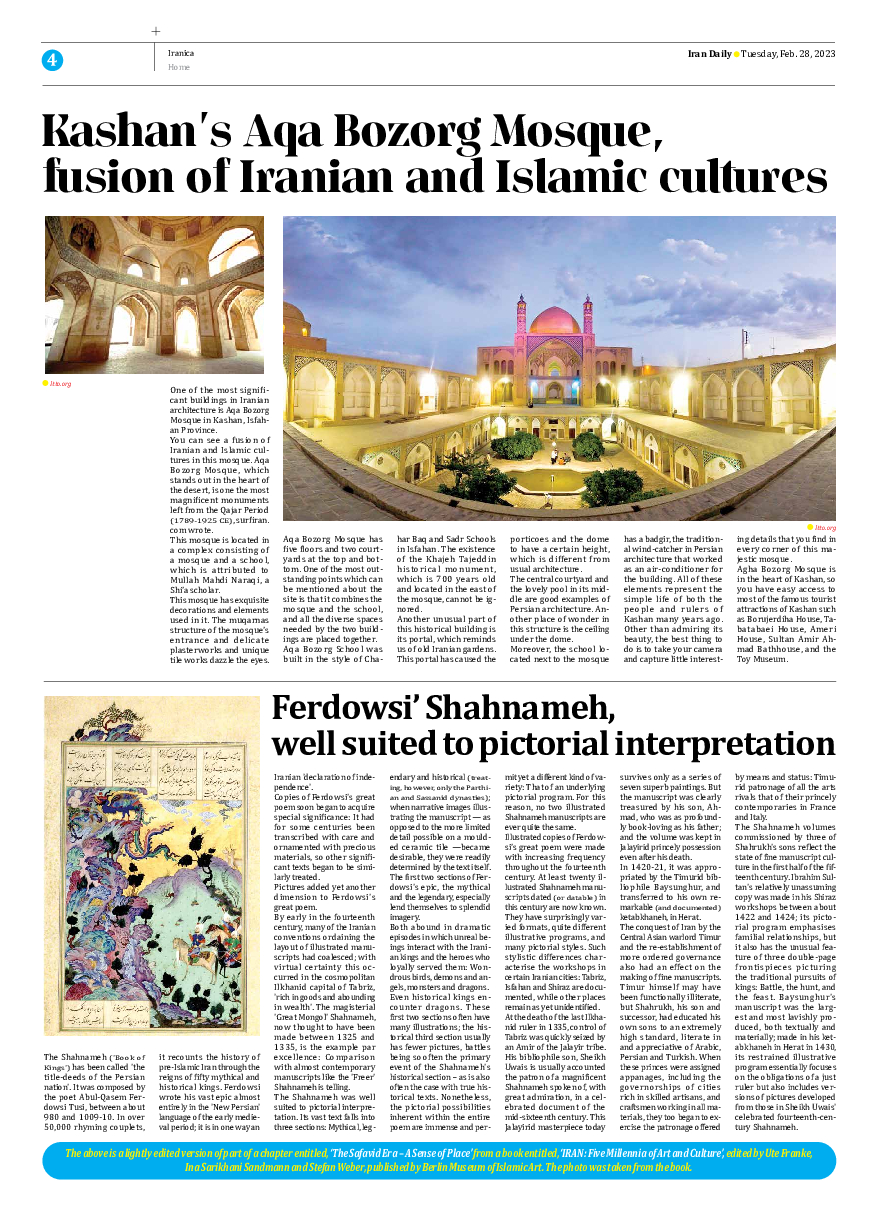

By early in the fourteenth century, many of the Iranian conventions ordaining the layout of illustrated manuscripts had coalesced; with virtual certainty this occurred in the cosmopolitan Ilkhanid capital of Tabriz, 'rich in goods and abounding in wealth'. The magisterial 'Great Mongol' Shahnameh, now thought to have been made between 1325 and 1335, is the example par excellence: Comparison with almost contemporary manuscripts like the 'Freer' Shahnameh is telling.

The Shahnameh was well suited to pictorial interpretation. Its vast text falls into three sections: Mythical, legendary and historical (treating, however, only the Parthian and Sassanid dynasties); when narrative images illustrating the manuscript — as opposed to the more limited detail possible on a moulded ceramic tile —became desirable, they were readily determined by the text itself.

The first two sections of Ferdowsi's epic, the mythical and the legendary, especially lend themselves to splendid imagery.

Both abound in dramatic episodes in which unreal beings interact with the Iranian kings and the heroes who loyally served them: Wondrous birds, demons and angels, monsters and dragons.

Even historical kings encounter dragons. These first two sections often have many illustrations; the historical third section usually has fewer pictures, battles being so often the primary event of the Shahnameh's historical section – as is also often the case with true historical texts. Nonetheless, the pictorial possibilities inherent within the entire poem are immense and permit yet a different kind of variety: That of an underlying pictorial program. For this reason, no two illustrated Shahnameh manuscripts are ever quite the same.

Illustrated copies of Ferdowsi’s great poem were made with increasing frequency throughout the fourteenth century. At least twenty illustrated Shahnameh manuscripts dated (or datable) in this century are now known. They have surprisingly varied formats, quite different illustrative programs, and many pictorial styles. Such stylistic differences characterise the workshops in certain Iranian cities: Tabriz, Isfahan and Shiraz are documented, while other places remain as yet unidentified.

At the death of the last Ilkhanid ruler in 1335, control of Tabriz was quickly seized by an Amir of the Jalayir tribe. His bibliophile son, Sheikh Uwais is usually accounted the patron of a magnificent Shahnameh spoken of, with great admiration, in a celebrated document of the mid-sixteenth century. This Jalayirid masterpiece today survives only as a series of seven superb paintings. But the manuscript was clearly treasured by his son, Ahmad, who was as profoundly book-loving as his father; and the volume was kept in Jalayirid princely possession even after his death.

In 1420-21, it was appropriated by the Timurid bibliophile Baysunghur, and transferred to his own remarkable (and documented) ketabkhaneh, in Herat.

The conquest of Iran by the Central Asian warlord Timur and the re-establishment of more ordered governance also had an effect on the making of fine manuscripts. Timur himself may have been functionally illiterate, but Shahrukh, his son and successor, had educated his own sons to an extremely high standard, literate in and appreciative of Arabic, Persian and Turkish. When these princes were assigned appanages, including the governorships of cities rich in skilled artisans, and craftsmen working in all materials, they too began to exercise the patronage offered by means and status: Timurid patronage of all the arts rivals that of their princely contemporaries in France and Italy.

The Shahnameh volumes commissioned by three of Shahrukh's sons reflect the state of fine manuscript culture in the first half of the fifteenth century. Ibrahim Sultan's relatively unassuming copy was made in his Shiraz workshops between about 1422 and 1424; its pictorial program emphasises familial relationships, but it also has the unusual feature of three double-page frontispieces picturing the traditional pursuits of kings: Battle, the hunt, and the feast. Baysunghur's manuscript was the largest and most lavishly produced, both textually and materially; made in his ketabkhaneh in Herat in 1430, its restrained illustrative program essentially focuses on the obligations of a just ruler but also includes versions of pictures developed from those in Sheikh Uwais' celebrated fourteenth-century Shahnameh.

The above is a lightly edited version of part of a chapter entitled, ‘The Safavid Era – A Sense of Place’ from a book entitled, ‘IRAN: Five Millennia of Art and Culture’, edited by Ute Franke, Ina Sarikhani Sandmann and Stefan Weber, published by Berlin Museum of Islamic Art. The photo was taken from the book.